Customized Digital Advice Can Help Farmers Reduce Crop Loss and Manage Weather Shocks: A Summary (or as Much as We Can Summarize!)

- February 26, 2025

- 14 minutes read

A randomized evaluation of Ama Krushi (now Krushi Samruddhi), PxD’s flagship digital agricultural advisory program in Odisha, India, finds that it helped farmers improve farming practices, boost agricultural production, and reduce crop losses. The largest impacts are found in areas hit by weather shocks such as excess or inadequate rainfall. Our calculations show that digital advisory services can deliver significant benefits at low cost, supporting tens of millions of smallholder farmers facing the consequences of climate change. Below is a summary of the key findings we report in this working paper.

Context

From 2018-2022, Precision Development (PxD) and the Government of Odisha (GoO) partnered to design, operate, and scale Ama Krushi, a free digital agricultural advisory service1Ama Krushi was designed as a “Build, Operate, Transfer” model and in 2022 PxD successfully transitioned the service to full government ownership. Read more on our blog. . To generate rigorous insights on impact, PxD and the GoO agreed early on to implement a randomized evaluation of the Ama Krushi service2PxD and GoO agreed to carve out five out of thirty districts – Anugul, Cuttack, Ganja, Jajpur, and Surendargah – with low initial penetration of Ama Krushi for the evaluation sample. These districts were not randomly selected but covered multiple agroclimatic zones..

Existing evidence demonstrates that digital advice can influence agricultural decisions among smallholder farmers in a variety of contexts, such as SMS-based advice in Kenya and Rwanda, site-specific fertilizer advice on smartphones in Nigeria, and video-mediated extension and IVR-based advisory services in India.

Importantly, a meta-analysis across seven studies measuring the impact on agricultural productivity finds that, on average, these services can boost crop yield. However, most studies focus on digital tools offering targeted advice on one or a small number of practices. In contrast, Ama Krushi was designed to serve large, diverse farmer populations with comprehensive advice on a wide range of farming practices throughout the agricultural growing seasons.

Key characteristics of Ama Krushi include:

- Two-way voice-based platform: Farmers receive weekly recorded messages with timely agricultural advice on their mobile phones. They can also call a hotline to access agricultural advice on demand, or record questions. Local agronomists respond to these questions with recorded audio messages, which are sent back to farmers within 48 hours.

- Comprehensive advisory content: Ama Krushi provides advice on a wide range of agricultural topics throughout the growing season, including pre-planting advice, soil fertility management, pest & disease control, and harvest/post-harvest processes. This service covers 21 value chains across crops, livestock, and fisheries.

- Real-time weather-based advice: The service provides real-time advice to help farmers reduce and mitigate damage from adverse weather events, such as cyclones, unseasonal rainfall, or inadequate rainfall.

- Localized pest & disease advice: The platform delivers real-time, localized advice based on the volume of questions about a particular pest or disease in a particular geography reported by farmers via the hotline.

Evaluation sample

This evaluation focused on rice advisory during the 2021 and 2022 “Kharif” seasons (the main agricultural season in India). We used random-walk sampling—a method that systematically identifies eligible farmers, to ensure that the evaluation sample would resemble the broader rice farmer population in the area. The final study sample included 13,675 farmers across 902 villages in 18 blocks of the five districts.

The reach of agricultural extension in this population was limited at the time of the study. Only 24% of farmers relied on traditional in-person extension agents for agricultural information, and fewer than 5% of farmers used mobile phones or the Internet to receive agricultural advice. Feature phones (not smartphones) were still the most common phone type, with 62% of farming households using them as their primary device. Women farmers made up 17% of the sample, with roughly half of them from a single-headed household.

Approach to measuring impact

In the evaluation sample, we randomly assigned farmers to either a treatment group, which received access to Ama Krushi, or a control group, which did not.3To minimize the spillover of information between the treatment and control farmers that might affect the impact estimates, we capped the proportion of farmers receiving access to Ama Krushi at 15% of farming households in each panchayat. We collected self-reported data via two rounds of follow-up surveys to measure Ama Krushi’s impact on farmer outcomes, including agricultural knowledge, practice adoption, rice yield, crop loss, and agricultural profits. We also attempted to estimate yields using satellite images but faced challenges with this approach (more on this later). The key findings we discuss in this blog are primarily based on the survey data collected from 5,204 farmers.

Key results

Notes: Unless noted otherwise, the results we highlight here are statistically significant at 10% after adjusting for multiple hypothesis tests (MHT). MHT is a statistical test that ensures that the observed effects are truly significant and not a fluke of random chance resulting from testing a large number of hypotheses.

High levels of service engagement were sustained over two seasons

Farmers received 45-50 advisory calls in a season. Most farmers—94% in Year 1 and 85% in Year 2—listened to at least one agricultural advisory call in a season. On average, they listened to the majority of the content in around 10 of the calls they received per season.

Ama Krushi drives overall improvements in agricultural knowledge, adoption, yield (kg/ha), and harvest (kg)

On average, treatment farmers who gained access to Ama Krushi had better agricultural outcomes than control farmers. The average yield was 1.7% higher per season, and the average harvest was 4.1% higher per season over the two Kharif seasons. To put these figures into perspective, the 4.1% increase in harvest is equivalent to 100 kg of harvested rice per farmer, or US$39 in value (at the retail price of rice in Odisha in 2021).

Ama Krushi drives a large reduction in the likelihood of severe crop loss

The reported incidence of crop loss was high in the second season when we collected data on crop losses—61% of control farmers without Ama Krushi lost some portion of their crop, and one-third of those lost more than 50% of their crop (“severe crop loss”). In comparison, treatment farmers with access to Ama Krushi had a 10% lower incidence of severe crop loss. Strikingly, this is driven by nearly 25% reductions in severe crop loss due to pests, diseases, and weather events other than floods.4Unfortunately, the way we collected data only allows us to distinguish flooding among the various types of weather events that affected farmers (this is a good lesson for future data collection!)

The largest impact was in areas affected by some (but not all) weather shocks

These large reductions in the likelihood of severe crop loss led us to test whether the service was particularly effective when farmers faced adverse weather conditions. Odisha, being a coastal state, faces frequent adverse weather events. We looked at the rainfall patterns and sifted through government reports on natural calamities to identify major adverse weather conditions that affected the study area during the evaluation period. We then compared the treatment impact in areas hit by each type of adverse weather conditions against the impact in areas that were not.

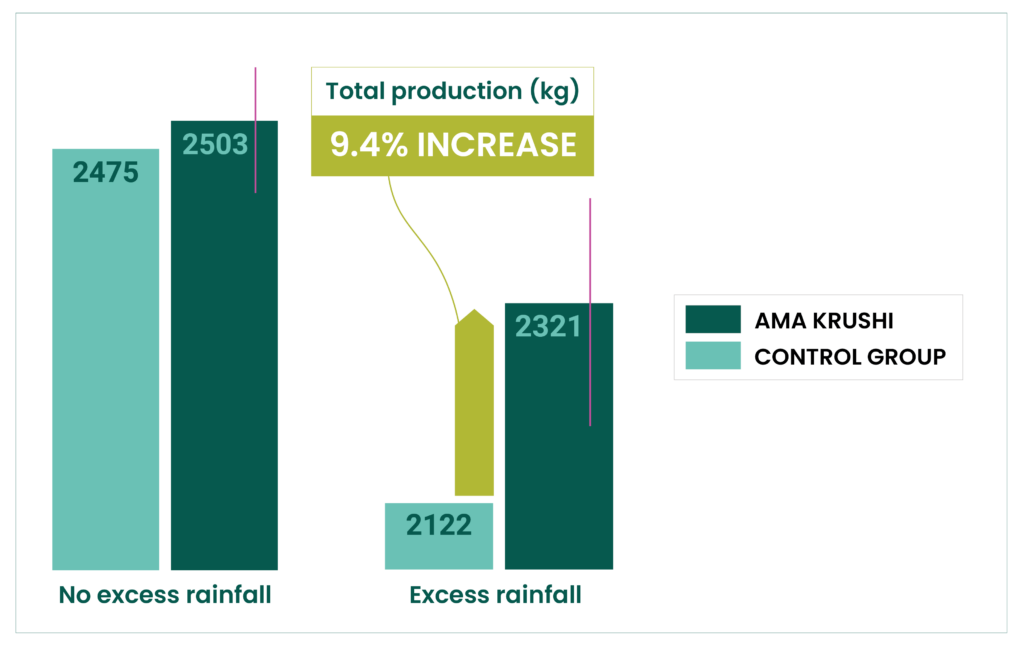

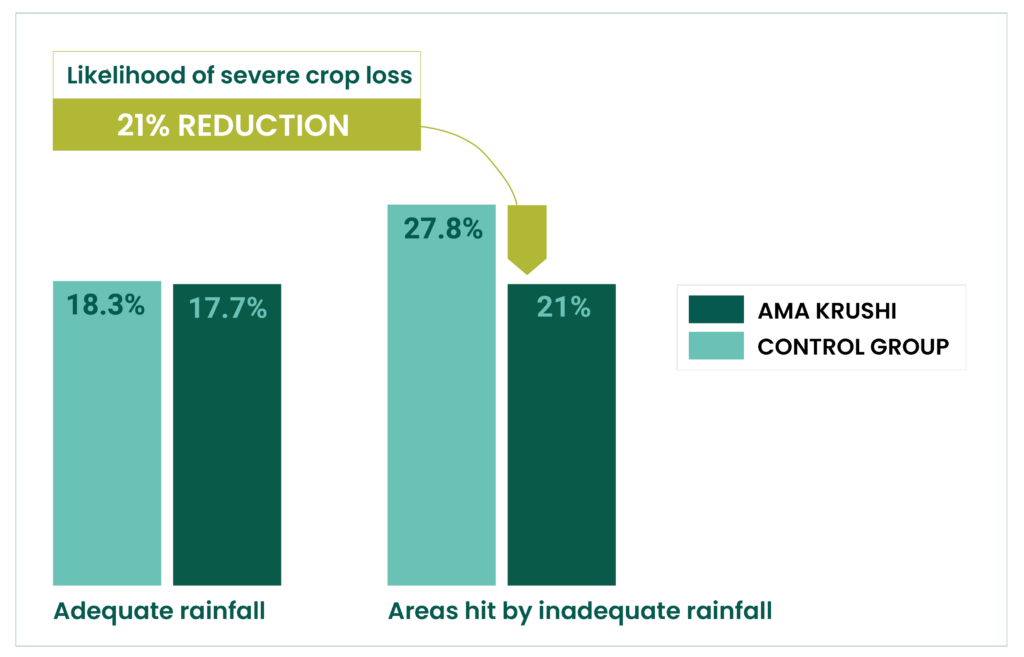

We find particularly prominent signs of large impact in areas affected by two of the four adverse weather conditions we identified: excess rainfall concentrated over a short period of time, which submerged a large number of plots in 7 out of 15 study blocks in Year 1, and inadequate rainfall, which exposed farms in a different set of 7 study blocks to severe water stress during the growing season in Year 2.

In these affected areas, treatment farmers with access to Ama Krushi consistently reported better agricultural outcomes than control farmers without access to the service. This includes a 9.4% increase in rice harvest in areas hit by excess rainfall in Year 1, a similarly large but statistically insignificant increase in rice harvest in areas hit by inadequate rainfall in Year 2, and a 21% reduction in severe crop loss in those areas hit by inadequate rainfall. (Unfortunately, we did not collect data on crop loss in Year 1.)

Importantly, Ama Krushi does not protect farmers against every weather-related shock. For instance, access to Ama Krushi did not improve agricultural outcomes in areas affected by the severe Mahanandi River flooding in 2022. There may be limited real-time advice that could help farmers mitigate the effects of an extreme event like this one.

Ama Krushi showed encouraging signs of increased profits

Profits are also meaningfully higher for treatment farmers with access to Ama Krushi in areas affected by excess rainfall, by US$26-39 per farmer depending on how we measure profits (only collected in Year 1).5For instance, farmers in our sample sold only 35% of harvested rice, and the bulk of unsold rice was likely consumed by the household; whether we value this unsold rice harvest at the sales price that farmers would earn by selling it or the retail price that farmers would pay at market (nearly double the sales price) makes a notable difference. This profit increase is the equivalent of 14-30% of the average profit from Kharif rice cultivation reported by control farmers in the study in the same year.

While this is an exciting finding, there is an important caveat. Measuring program impact on agricultural profits is particularly challenging because of both measurement errors and large natural fluctuations in agricultural outcomes across seasons. Our self-reported profit measures have very large variances, meaning that our analysis leaves some uncertainty about whether increased profits were just caused by random chance. The profit impact estimates, however, present patterns consistent with the robust impact estimates on other agricultural outcomes across the board. We take these results as suggestive evidence of increased profits.

Challenges of measuring agricultural yield using satellites

Impact measurements that rely on survey data often raise concerns about the validity of self-reported measurements and the influence of survey attrition. Satellite imagery offers a potential solution by providing an objective measure of yield (i.e., a vegetation index) and eliminating biases from farmer recall and survey attrition. To estimate the impact of Ama Krushi using satellite data, we collected plot boundary data for each farmer’s primary rice plot during the baseline survey.

We encountered several challenges in measuring agricultural yield with satellite imagery over multiple seasons. In eastern India, farmers typically cultivate very small plots, with most under 1 hectare. The smaller the plot, the harder it is to generate a precise model that captures the relationship between satellites and true yield. More importantly, our analysis suggests that farmers change the areas they cultivate within their rice plots across seasons. This means that the vegetation index for the area identified in the first season may not accurately capture the farmer’s yield in the following season.

We did find, however, that satellite data offer valuable insights, allowing us to validate our survey-based findings. This confirmed that our survey results are not driven by differences in reporting biases or follow-up survey attrition between the treatment and control groups in our setting.

We plan to share more insights on this effort in a future blog, so stay tuned!

How does Ama Krushi help farmers cope with weather shocks?

Our key finding is that Ama Krushi helps farmers cope with weather-related shocks such as excess and inadequate rainfall and pests. There are three types of Ama Krushi advice that are relevant here:

- Precautionary practices that could improve plant resilience to adverse shocks (e.g., flood- and drought-tolerant seeds, seed treatment),

- Real-time preventive practices to mitigate potential damage (e.g., improving water drainage, harvesting before rainfall), and

- Reactive management practices to minimize damage (e.g., re-applying fertilizers after submersion, applying pesticides).

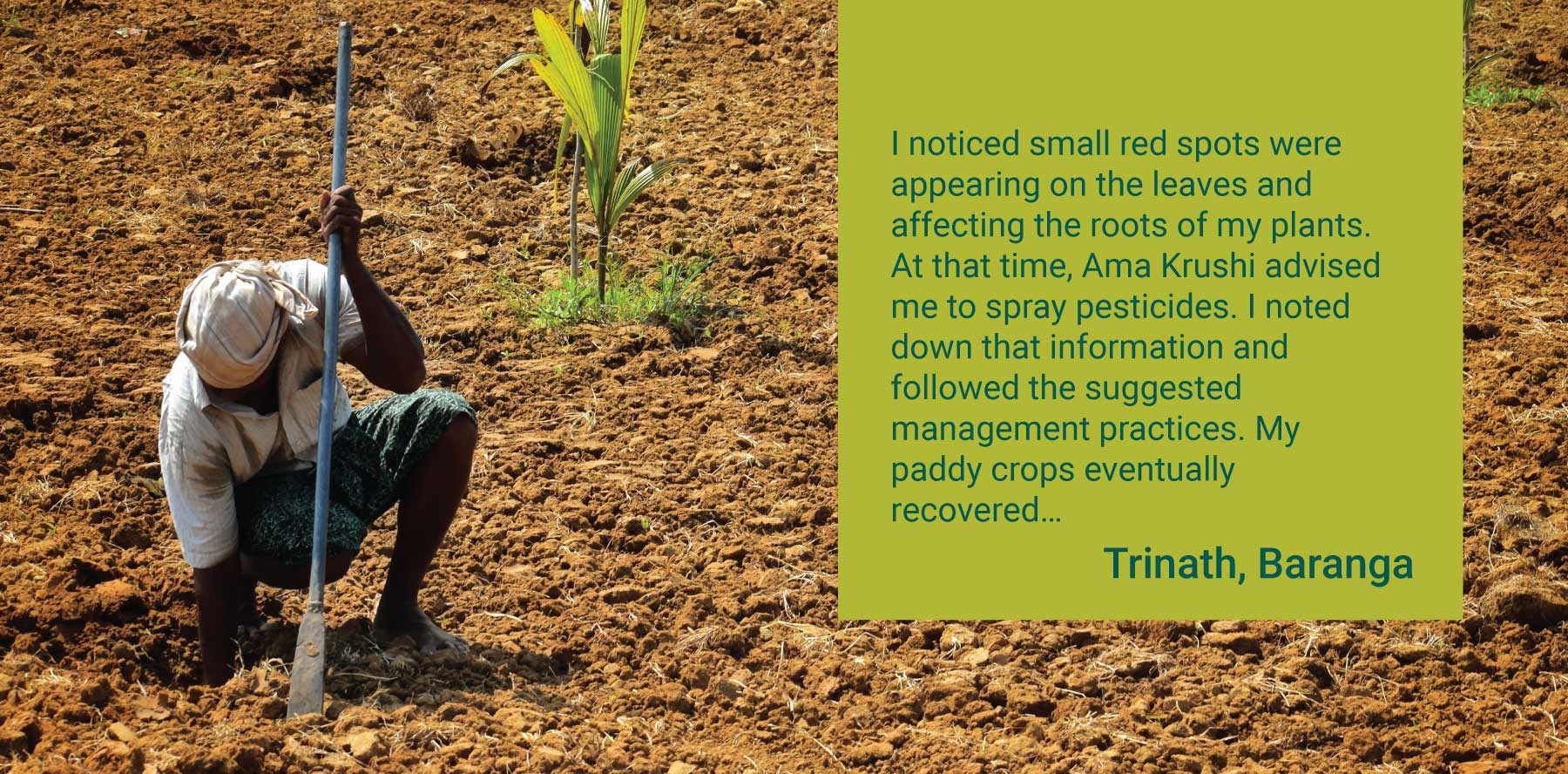

We did not collect sufficiently granular data on the timing of specific agricultural practices to pin down the impact mechanisms. In qualitative conversations, however, farmers shared anecdotes that help contextualize our findings. For example, some farmers shared that they noted down pesticide advice while listening to Ama Krushi messages and brought the notes to agro-dealer shops. One farmer told us that, after seeing improvements in field conditions from acting on the advice from Ama Krushi, he shared the advice with neighbors struggling with the same pest. Other farmers talked about the effectiveness of advice on excess water drainage after heavy rainfall.

Benefit-Cost Ratios (BCR)

One key advantage of digital information services is their potential to reach millions of farmers at a very low marginal cost: the returns to investment can increase dramatically with scale.

Our calculations suggest that, in 2021, the aggregate benefits were 6 to 18 times larger than the total cost of delivering the service to the 1.37 million farmers in the state who had access to Ama Krushi that year. 6This assumes that the service generated the same magnitude of impact in non-study areas of Odisha as observed in this evaluation.The range of BCRs reflects variations in the methods used to measure profits (see footnote 5).

We calculate a long-run BCR of 9:1 to 15:1 at a steady state with at-scale farmer reach and cost of service delivery. These calculations are based on our estimates of the profit impact in areas affected by excess rainfall alone: we extrapolate those estimates by the average proportion of farmers affected by excess rainfall over the last 10 years.

Importantly, the true returns to investing in services like Ama Krushi can be substantially larger than the measured impact, and could further increase over time with improved customization. For example, the majority of farmers with Ama Krushi also reported sharing advice with neighbors and friends, but these positive spillover effects are not captured in our impact measurements. Furthermore, the service provides advice on many other crops throughout the year, but our impact measurements only capture the impact on rice cultivation in Kharif. Of course, several factors could dampen returns over time, with the most significant risk likely being the challenge of maintaining the quality of dynamically tailored advice across a large user base. 7Recent advances in generative AI using large language models may reduce the challenge and cost of customizing advice in the future. This is an exciting area that PxD is starting to work on.

While the same caveats about the uncertainty of estimated profit impacts apply to BCR calculations, this exercise illustrates the high cost-effectiveness a digital agricultural advisory service can achieve at scale.

Using the insights for future work

There is already robust evidence that well-crafted digital messages can influence farmers’ decisions and improve their welfare. Our study’s findings add important new insights to this growing literature.

First, Ama Krushi is a mature, government-owned service that reaches millions of farmers, as opposed to a pilot intervention delivered to a small number of farmers in a controlled setting. Two years after the evaluation, the service continues to serve over 7 million farmers with new features and content being introduced. Our results are encouraging: a digital agricultural advisory service can generate large impacts at scale and with long-term sustainability.

Second, Ama Krushi incorporates dynamic information, such as real-time weather and local information on field conditions, to deliver targeted advice that helps farmers navigate adverse events throughout the season. Our results suggest that advisory services designed to improve farmers’ capabilities to manage these risks could generate a large per-farmer impact among vulnerable farmer populations.

At PxD, these incremental learnings about our impact directly inform our investments and service design. We’re actively exploring new collaborations to enhance farmers’ access to real-time, localized information—such as weather forecasts—and are prioritizing risk management in our services to help smallholder farmers better adapt to the challenges of climate change.

Acknowledgment

This evaluation was conducted in collaboration with Jessica Goldberg (University of Maryland), and Shawn Cole (Harvard Business School), PxD’s co-founder and a board member. We are grateful for the generous financial support of the Gates Foundation and the Wellspring Philanthropic Fund and to the Government of Odisha for collaboration and support.

Stay Updated with Our Newsletter

Make an Impact Today