Punjab means “five rivers”, and those five rivers are the reason that the Punjab region in Pakistan is the country’s bread basket. Tomoko and I were in Punjab last week visiting the PxD Pakistan country team. As many of you will know, PxD in Pakistan is housed within a local economics research institute, CERP, a partnership that has enabled us to be more effective and flexible.

This week much of our attention has been on smallholder rice production. The staple food in Pakistan is of course wheat (for roti), but rice is a major crop for both domestic consumption and export. (We were in town at the same time as the IMF delegation, negotiating a package of macroeconomic reforms to stabilise the economy, so those export earnings are important right now).

Punjab is famous for its basmati rice, a variety much prized for its aroma, fluffiness and grain length. It is very popular in traditional dishes like biryani and pulau. We visited Kala Shah Kaku Rice Research Institute, established in 1926, where basmati rice varieties have been developed since the 1930s. Farmers in Pakistan typically grow wheat in the Rabi season and then many grow rice in the Kharif season, especially in the basmati belt in Punjab. The yield of basmati rice is around half as much per hectare as hybrid rice varieties, but it sells for around twice the price, so generating similar revenues and broadly similar net income per hectare. (An exciting development on the horizon is the prospect of hybrid basmati rice that may have a much higher yield while retaining much of the quality for which basmati rice is famous.)

Many of the people we met were keen to stress that Pakistan, rather than India, is the home of basmati rice. I’d be very glad if the rivalry between these two great nations were confined to arguing about the origin of basmati rice and, far more importantly, their relative prowess in cricket.

Pakistan’s farmers produce on average around 4 tonnes of rice per hectare, about the same as in India. In China, the yield is 7 tonnes per hectare and in Australia 10 tonnes per hectare. The yield gap (that is, the gap between what farmers produce and what they could produce with the land and other inputs available to them) is estimated to be about 50% – about 3.5 tonnes per hectare – for basmati rice, and closer to 60% – 6 tonnes per hectare – for the higher yield but lower price varieties. In other words, farmers could, in principle, at least double their yields. So what is holding them back?

You would expect farmers to be more interested in increasing their profit than their yield, so one possible explanation – in theory – could be that the additional inputs are too costly, and the value of the extra output does not justify the investment. In that case, it would be rational for farmers not to increase their output this way. But that doesn’t seem to be the problem. The additional cost of the recommended inputs, at market prices, is small relative to the price that basmati farmers could get for the roughly extra 3-4 tonnes per hectare that they could be producing. Despite extra input costs, the extra yield on this scale would lead to much higher profits – perhaps multiples of profits now being earned. If you are doing only a little better than breaking even, then moving to a reasonable surplus could mean a transformational increase in net income.

So what is getting in the way? We spent two days in villages outside Lahore talking to farmers, extension agents, and private and public sector experts to try to get a better picture.

My main take-away is that it seems that expensive credit for agricultural inputs and low prices paid by middlemen (called aahrtis) leaves farmers with little surplus. Farmers are unwilling to take on a large, expensive debt which – if the harvest is bad – they may not be able to repay, especially when they know that a big chunk of any profit, if the harvest is good, will go to the middleman. So they stick to limited use of inputs, which gives them lower yields and less debt and thus lower risk. Thus it is the cost of credit, and the associated risk, rather than the cost of the inputs themselves, that stops them from investing more.

I’m conscious that we met farmers close to Lahore, who are relatively well-off, and who are already in contact with extension services. So we should be careful about drawing too many conclusions. Based on these few conversations with an atypical group of farmers, I find it hard to convince myself that there are very many practices that farmers could adopt that they do not already know about. That said, there may be some value to encouraging practices that cost the farmer little or nothing to implement – or which save inputs such as using the right amount of urea – for example by issuing timely reminders. But it looks as if the larger gains would come if we could find a way to reduce the risk of increased investment in inputs, reduce the cost of credit, provide high-resolution weather information, or perhaps improve planning and coordination in the use of scarce machinery or casual labour.

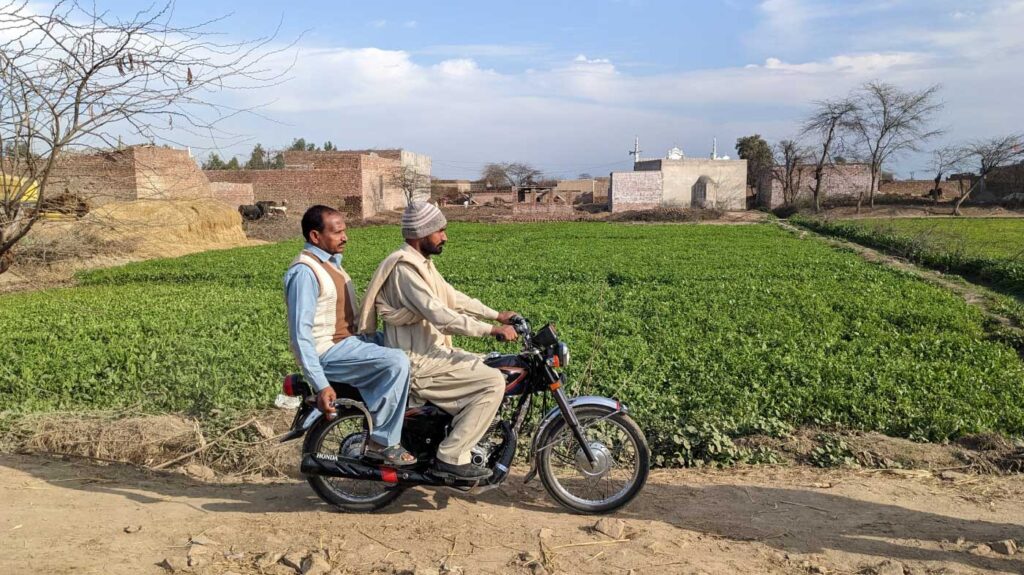

It is harder to notice what is missing than what is in front of you. As you may see from the photos, we did not meet any women farmers. We met a female scientist at the rice institute, but everyone else we spoke to was a man. In every conversation, farmers were routinely and unthinkingly referred to as “he”. Yet we know that women provide a substantial part of labour in agriculture, and are hugely affected by all the decisions that are made. If we want to understand what it would take for farmers to adopt practices that would increase their yield and their incomes, we are likely to learn a lot by talking to women too.

I leave Pakistan optimistic but uncertain. Optimistic because the opportunities are huge for large increases in yield and potentially transformative increases in farmer incomes. The constraints are real, but there may be solutions that have a low marginal cost per farmer and so would be hugely cost-effective at scale. Uncertain because we do not yet have enough information to arrive at robust ideas for higher-impact services that we could design and test.

I want to thank Adeel, and all the team, for giving up so much of their time and energy to host us – including taking us to the old Walled City of Lahore to have dinner overlooking the famous Badshahi Mosque (Mosque of Kings) and the Lahore Fort (Shahi Qila in Urdu), an ancient citadel of the Mughal Empire. I look forward to returning to Pakistan soon and hope to combine my next trip with some tourism in your beautiful country.

When disease and a heatwave, followed by devastating floods ravaged Pakistan’s Punjab province, PxD’s LMAFRP digital information service, which we implement in partnership with the Rural Community Development Society (RCDS) with support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), assisted women livestock farmers navigate new and unprecedented challenges. This International Day of Rural Women, we highlight the important role women play in Punjab’s rural farming economy and our work to promote information to enhance more productive and resilient livelihoods.

Introduction

Livestock husbandry and livestock-related products (dairy, meat, leather goods, etc.) constitute an important sub-sector of Pakistan’s agriculture sector: Pakistan is the fourth largest milk-producing country in the world1Sattar, Abdul, “Milk Production in Pakistan” PIDE Blog, pide.org.pk/blog/milk-production-in-pakistan , and the share of livestock products in the generation of foreign exchange is approximately 13%2Government of the Punjab, “Livestock Contribution” , livestock.punjab.gov.pk/livestock-contribution. As is the case in many smallholder economies, in Pakistan, women are largely responsible for the care of livestock and for the production of many livestock-related products, particularly dairy3Ibid..

In rural areas, livestock plays an outsize role in livelihoods, with the Punjab provincial government estimating that “livestock is an integral part (30-40%) of the livelihood of about 30 to 35 million rural farmers”4Ibid.. Livestock-related products, such as butter, eggs, meat, and animal fats (oils), contribute important nutrients for all households – rural and urban – and play a critical role in meeting the nutritional needs of rural children. Further, livestock contribute an important source of continuous income which can sustain poor rural households between seasonal crop-related revenues, and insulate them from shocks5Ahmad, Tusawar Iftikhar and Tanwir, Farooq, “Factors Affecting Women’s Participation in Livestock Management Activities: A Case of Punjab-Pakistan”, mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93312/1/MPRA_paper_93312.pdf..

For these reasons and more, supporting the development and improvement of livestock farming can have a considerable impact on improving the livelihoods of Pakistan’s rural population, and can impact the livelihoods and status of rural women. We believe significant gains can accrue to rural farming families through the promotion of best practices to women. Improved practices can improve yields and minimize losses, leading to increases in income from livestock farming.

Many rural women are unaware of best practices that can optimize outputs associated with livestock, and access to information and economic opportunities can be constrained by cultural and geographic barriers. As documented elsewhere on this blog, digital extension services offer cost-effective and easily scalable solutions with very low marginal costs. In rural Pakistan, where many women rarely leave their homesteads, the portability of digital information offers additional advantages for navigating geographically and culturally hard-to-reach spaces.

Geographic and cultural constraints to attending in-person RCDS livestock training sessions were exacerbated by social distancing introduced to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. RCDS’s in-person activities were suspended in the initial months of the pandemic, but the utility of advisory information increased as rural households navigated new challenges in a time of escalated economic stress. It was at this time that RCDS and PxD initiated a partnership to deliver advice to livestock-rearing women in rural regions of Punjab province in Pakistan. This collaboration, supported by IFAD, provides customized and actionable digital information to livestock-rearing women. Combining PxD’s experience in delivering digital extension services to Punjabi farmers and RCDS’s extensive local knowledge and expertise, the service draws on demographic insights, and cultural practices to deliver information that is accessible, comprehensible, and actionable for recipients.

The resultant digital advisory service has proven to be an effective, cost-efficient, and scalable supplement to in-person training, and is now extended in the absence of COVID-19-related social-distancing constraints. The service demonstrated new advantages when unfamiliar disease- and climate-related threats subsequently impacted rural households.

The Service

RCDS’s experience and local trust in their services have been integral to the success of the initiative. Over the past two decades, RCDS has partnered with local, federal, and international institutions to build a significant rural network to promote and implement development programs to assist poverty-stricken segments of society in rural areas of Pakistan.

Advisory content was developed in partnership with local livestock consultants who were well-informed about local livestock issues and output-increasing best practices. The advisory information distributed by the service covers a wide array of topics, including disease identification, information about and access to vaccinations, disease prevention and remedies, practices to increase milk yields, and guidance on protecting livestock against climate-related shocks.

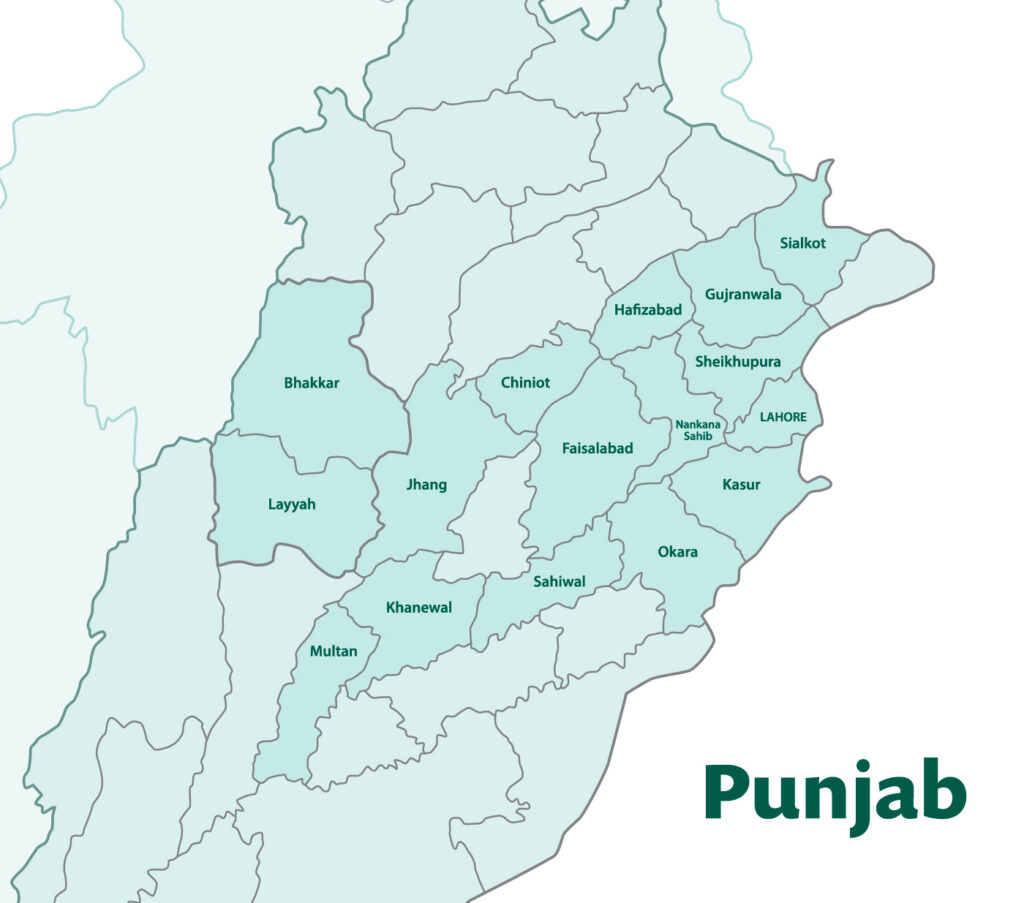

After conducting a baseline survey to systematically understand the informational needs of women farmers in four districts in Punjab, and the development of advisory information, PxD piloted digital services among 3,160 rural women associated with RCDS. The four districts, in which the pilot was concentrated, are among the poorest districts of Punjab, all of which are located in the south of the province. Given the success of the initial pilot, the service has subsequently been expanded to more than 50,000 livestock-rearing women in 16 rural districts of Punjab.

One of the key components that PxD assessed during the initiative was the extent of knowledge retention by participating women after they received the advisory. Pilot testing in the early stages showed that the advisory information was not only useful but was also retained for a significant period after it was delivered.

RCDS maintains a dataset of women who have either attended in-person sessions of livestock advisory or shown an interest in livestock advisory or have taken a microfinance loan for livestock farming. This data, and its quality, were instrumental in helping PxD deliver the advisory directly to the women via their phones. Furthermore, the data also contained the districts in which each woman resided. This was used to help decide in which of the two local languages – Punjabi and Saraiki – the advisory would be conveyed.

Advisory information is delivered through a voice call. A text message is sent 24 hours before the call to alert users that they should expect a call the next day. This is done to ensure that the advisory is received by women. A barrier highlighted by the baseline survey was limited access to mobile phones on the part of women in the region. Cultural and financial constraints make it far more likely that men have primary access to cell phones. Hence, the time allotted for the voice calls is set at a specific hour in the evening, so that the call is received in the evening when the family is no longer busy with agricultural activities, men are more likely to be home, and when family members can collectively listen to the advisory in their homes.

The voice call has local cultural music layered in the background, to assist the participant in developing trust in and comfort with the message. The information is delivered in the local dialect – Punjabi or Saraiki – to enhance understanding of and familiarity with the recorded message. Further, listeners are told that the advisory is from RCDS since it is well-known as a trusted organization in these regions. As a general protocol, to improve pick-up rates when the voice call is unanswered, another call is placed after a 15 to 30-minute interval.

Lumpy Skin Disease

A significant advantage of digital extension is the ability to send timeous information. This is particularly valuable to address and prevent viral diseases that can have a drastically negative impact on the well-being of the livestock.

In April 2022, Pakistan saw a viral outbreak of lumpy skin disease in cattle. The disease was transmitted between cattle via blood-feeding insects. The disease has a high virulence and fatality rate and killed thousands of cattle in the country.

A significant hurdle that seriously hindered timely prevention and actions to curtail the impacts of the infestation was the lack of baseline knowledge and awareness of the disease. Moreover, misinformation was rife, with misplaced rumors about negative effects of vaccines abounding. Many people mistakenly believed that it was the vaccines that were causing deaths among animals, when animals that had died were either already infected with lumpy skin disease, or were generally sick and should not have been vaccinated at the time.

Understanding these knowledge gaps, PxD and RCDS collaborated to provide timely information about the infestation. Initial infections were observed in the southern part of the country and slowly spread north towards Punjab province, where our users reside. PxD started providing information about lumpy skin before the disease had become widespread in the province.

Our farmer-users were given information about the disease and its virulence, how it is spread, and traditional preventative measures. Following that, to increase the survival rate of infected cattle, users of the service were advised to vaccinate their cattle as soon as vaccines became available. Participants were also informed about how to identify early signs of the disease on the animal.

Anecdotal feedback received by RCDS in the field suggests that the messages were very useful. Users with whom PxD surveyed reported that in many instances they were able to avoid fatal infections in their animals due to timely vaccines, even if their animals did get infected.

The Floods

In the summer of 2022, Pakistan witnessed firsthand the severe impacts of climate change. In March and April, the country experienced a crippling heat wave, followed by a record-breaking monsoon season in Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan spanning June, July, and August. An unparalleled monsoon, coupled with unprecedented melting of glaciers in the north due to the initial heatwave, led to extreme flooding in rivers that flow from the north of Pakistan to the south. The floods are estimated to have impacted at least one-third of Pakistan, including the livelihoods of 33 million people.

Prior to the floods, the extreme heat waves had contributed to a general belief that floods were imminent. To counter the threat, the PxD team in Pakistan worked with RCDS to preemptively identify areas prone to flooding, and prepare advisory messages with useful information about managing floods, and adaptive strategies to protect assets and livelihoods.

A major problem with livestock is their slow mobilization, making them and their rearers prone to becoming flood victims. Timely warnings and regular updates via voice call advisory messages provided participants with information for ensuring the safety of their livestock during the floods. PxD and RCDS made use of their existing program to deliver instructions, warnings, measures, and assistance via voice call messages, to inform participating women and their families about floods and ways to protect themselves and their livestock.

Meeting today’s challenges

The advisory service designed by PxD, and delivered in partnership with RCDS, provided an effective method to deliver timely information to livestock farmers. Due to its effectiveness in the regions where it was being delivered, the advisory service was extended to address other unforeseen challenges, such as the virulent lumpy skin disease, and flooding.

In addition, our project has demonstrated the core strengths of digital communication: it is cost-effective, scalable, and capable of reaching regions and communities that are disconnected or hard to access due to difficult terrain, long distances, or cultural constraints.

Our advisory content was designed to deliver information in a manner that does not require the recipient to have prior knowledge, or education to understand the subject. The use of familiar dialects and carefully crafted messages made the information accessible, easy to understand, and ultimately very effective.

PxD aims to further extend the benefits of digital communication to support other low-cost interventions among rural communities of Pakistan. More specifically, feedback received from users has prompted PxD to further our partnership with RCDS to envisage interventions to support digital veterinary services. We are motivated to continue to harness the power of digital communication to facilitate more productive and resilient livelihoods in rural communities of Pakistan.

In consortium with Rare and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), PxD received a one-year grant from UK PACT in December 2020 to support the implementation of a project to promote sustainable and productive agriculture through behavioral change. PxD’s Colombia team – activated remotely under pandemic conditions – implemented the project over twelve months, sending climate-smart agricultural advice to smallholder farmers in Colombia’s Meta region. The main focus of the advice was to provide farmers with “win-win” recommendations to concurrently increase crop productivity and reduce environmentally harmful farming practices. The project was PxD’s first in the Americas and was unique in a number of respects – including a high penetration of smartphones among the user base, and an environment and digital culture profoundly shaped by a legacy of conflict.

What was the program about?

PxD, Rare, and TNC partnered to provide a mixed digital and in-person agricultural extension service called “New technologies, mentalities, and practices to transform Colombia’s agricultural sector.” PxD implemented an all-digital component of the project named “Un Mensaje por el Campo” (A message for the field), a two-way SMS service intended to increase crop productivity through the implementation of climate-smart practices for 2,800 farmers. PxD and Rare jointly designed and iterated 37 weeks of content timed to the production cycle of three crops – plantain, cocoa, and coffee – with a focus on practical knowledge such as composting, pruning, and pest and disease management. In addition to advisory promoting climate-smart production of these three primary crops, we also sent content to support the cultivation of perennial crops (the most common being avocado and citrus). To complement the digital approach, our partner Rare implemented an extension service to promote the adoption of sustainable practices by “innovative producers” (understood to be farmers more inclined to include sustainable practices in their day-to-day routines). Concurrently, TNC conducted a community-based pilot to measure carbon emissions.

Our digital platform featured multiple channels for farmer communications: Farmers received push-SMS recommendations weekly between 5:30 and 6:30 pm on Wednesdays and Fridays. In weeks when we were promoting complex topics, we sent recommendations three times a week. Farmers could also send an SMS with the word “menu” to access a repository of all content shared to that point and pull any information they needed. The menu was updated weekly as new content was pushed to farmers. Users could also send questions to our short-code at any time to be answered by our agronomist.

Farmer profile information received through PxD profiling surveys:

- 40.2% women users

- 66.3% reported owning a smartphone

- 35.5% have access to some form of extension services

- Farmers reported average land holdings of 8 hectares.

- 93.8% reported completing at least primary education

- 67.8% reported owning their land and 21% leased the land they worked. Of the remaining 11% of respondents, 8% worked collectively owned land shared with other farmers, 3% were share-croppers renting a piece of land from a permanent owner.

Armed history of the Meta region in Colombia

Building a new program in a region deeply scarred by conflict was demanding and gratifying. Even after the peace agreements, farmers in conflict-affected areas report very limited access to extension services as a result of reluctance on the part of in-person extension providers to visit farmers in areas perceived to be unsafe. Digital extension services can be particularly relevant in these contexts, as digital services can be deployed and managed remotely and can be customized to a region’s particular needs.

In general, farmers in post-conflict regions report limited trust and interaction with government services, including public extension services, and are often reluctant to interact with organizations they do not know.McNamara, P. & Moore, A. (2017). Building Agricultural Extension Capacity in Post-Conflict Settings. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12010/17029.

To improve the likelihood of success, a key challenge for the teams was to build trust in our service while building a program capable of reducing information asymmetries.

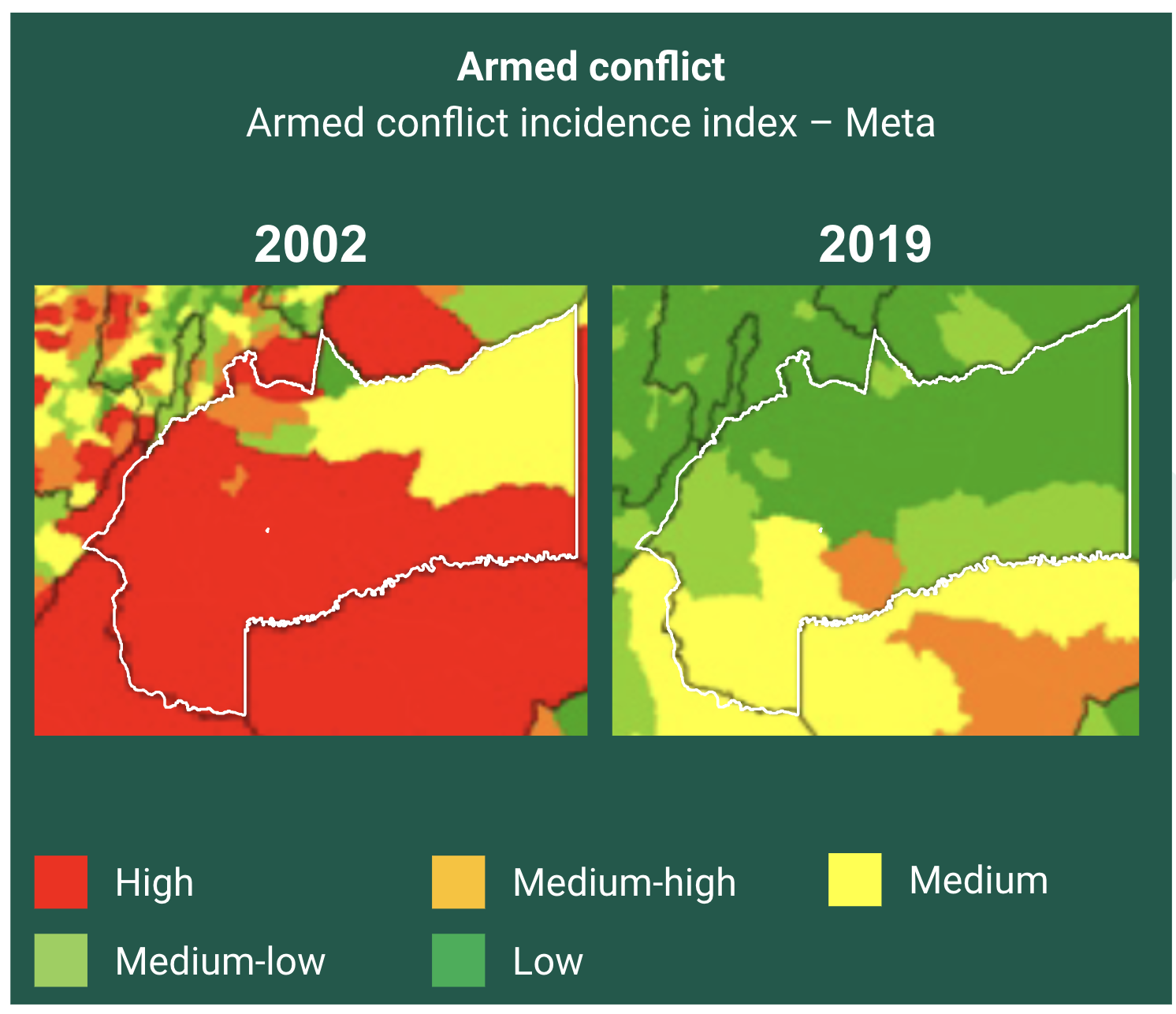

The Meta was the fourth-most conflict-affected region in Colombia in the early 2000s. The map above compares the armed conflict incidence index of 2002 to that of 2019. The index synthesizes six key conflict-related variables: homicides, kidnappings, anti-personnel landmines (number of events), force-displacement, coca crops, and armed actions (from illegal armed groups).

Source: National Planning Department (2021)

How did we measure results from engagement?

Our team used monitoring data to improve our contextual understanding of our user base, to help us identify opportunities for service improvement, and to measure program and intermediate outcomes along a theory of change. As a two-way SMS service, we measured engagement in two ways, which we dubbed “active” and “passive” engagement.

Active engagement was defined as engagement we could measure through PxD’s Paddy platform, the in-house tech platform we used to deploy Un Mensaje por el Campo. Such engagement included accessing the menu (by sending an SMS), replying to content threads, and sending an SMS question to our shortcode. We adopted the “reply 1” feature for most messages to enable users to choose what content they wanted to receive. A generic message such as, “Today we are going to talk about [topic of the day, state the importance of the topic, reply 1 if you want to learn more” invited an initial response. By the end of the program, 23% of users had actively engaged with the service (649 users had actively interacted with the platform at least once as of February 2021). Messages that did not require the “reply 1” feature were usually about topics we considered essential and wanted all farmers to read about. It is thus very likely that a much greater share of farmers read the messages but did not respond. We defined passive engagement as users who reported reading SMS messages via our monitoring surveys. For passive engagement, 56% of our users reported reading our SMS in the polling survey.

Polling survey findings

We conducted a monitoring and polling survey approximately six months after the commencement of the service. The polling survey aimed to measure practice adoption and service satisfaction. Results for the three primary practices were as follows:

- 36% of respondents reported preparing and applying compost, a practice we emphasized, and 16% (of the 36%) reported doing so for the first time. The soil quality and lack of organic content in the region make composting one of the most economically efficient ways for farmers to replace chemical fertilizers. This is especially relevant in light of significant price increases for agricultural inputs.

- 67% of respondents reported pruning their main crop, and 20% (of the 67%) reported doing so for the first time. Pruning is known to be one of the most effective ways of preventing pests and diseases without using chemical fertilizer.

- 60% of respondents reported applying chemical fertilizer, and 14% (of the 60%) reported doing so for the first time. Given that most farmers use chemical fertilizer, we provided advice on how to use it more efficiently, rather than expecting all farmers to switch exclusively to sustainable practices. Our recommendations focussed specifically on reducing the overuse of chemical fertilizers to minimize environmental degradation and reduce costs.

Respondents were generally enthusiastic about the service. In terms of service satisfaction:

- 75% of respondents reported the content as being relevant to the needs of their crops.

- 88% of respondents said they were likely to recommend our service to neighbors.

- 70% of respondents reported sharing content with their networks, and 59% reported having done so in person. (Great opportunity to explore how farmers not in the service benefited from the information!)

Challenges and learnings

We confronted many challenges over the 12 months of the program. Some had been encountered previously by other PxD teams, and we greatly appreciated their support in navigating the same challenges in a new country. Other difficulties were exclusive to Colombia, and we had to learn to face them with different strategies. We divided our challenges and learnings into content creation, trust-building, and SMS service and network.

Content creation:

To ensure our content was accessible to farmers, we explored ways to time the messages based on evidence from what had worked well in other PxD programs and on Colombian farmer feedback. After a few weeks of sending content, questions such as “How often should we send messages?” and “How often should we repeat content?” started to arise. Following support and advice from other PxD teams, and analyzing evidence from A/B tests, we decided to repeat the most important content at least twice to increase users’ exposure to it. We also implemented “weekly recaps” for which we dedicated a day to highlighting the most important messages of the week.

We also explored opportunities for customization so that farmers could maximize the benefit of our service based on their specific situation. After talking with the Nigeria team, which implements strategies such as creating personas to create the best possible message, taking into account different characteristics, we were able to decide on the best next step. We agreed that after crop segmentation, having customized content based on the agro-ecological zone (rainfall regimes) and based on the users’ technological level would be an appropriate next step. Unfortunately, the project’s implementation horizon did not allow sufficient time to achieve this level of customization.

We were also able to improve efficiency in the content creation process along the way. We worked towards reducing the number of iterations it took to get to a final message, while ensuring that the content remained of a high quality. By the end of the 12-month implementation period, we had settled on the following standardized template to design an SMS: Introduce the topic → Explain why the topic is important → Explain our recommendation → Explain how the activity should be performed.

Building trust

One of the most important steps when introducing a digital extension service is creating a relationship with farmers. A strong relationship translates into trust, which increases the potential impact of the service through increased engagement, asking questions, and recommending the service to loved ones. However, previous high exposure to armed conflict made farmers initially reluctant to receive and interact with the service. Moreover, users’ phone numbers were collected by Rare (our on-the-ground partner) and farmer associations, and many users were unaware of their enrollment in the advisory service when they started receiving messages. To improve our relationship with farmers, we implemented four strategies:

- Leverage local networks to build trust in the service. We contacted leaders of farmer associations and mayors of municipalities and asked them to help us spread awareness of the program through monthly meetings with farmers and WhatsApp groups.

- Always send SMSes from the same short code so that farmers become accustomed to it.

- Conduct onboarding calls to all farmers in our database to introduce the program to them and facilitate trust-building, and complement the calls with fieldwork. (We also conducted the onboarding call when new farmers were added to the program.)

- Provide users with an easy name they can think of when talking about the service, e.g. “Un Mensaje por el Campo” (some of our users had our contact saved with this name!)

SMS service and networking:

High variance in connectivity quality among municipalities in Colombia in general and in the Meta region in particular was a significant challenge. Some users only received messages when they went to the municipal center (e.g. on Sundays when farmers traveled to buy groceries). This is both a blessing and a curse, as while farmers did eventually receive the messages, the messages could not be precisely timed, which could hinder trust. Repeating content and leveraging weekly recaps to ensure priority recommendations were getting across to users thus became more critical.

Another characteristic of the Colombia program was that users were unfamiliar with SMSes despite the medium being considered the best option in light of connectivity challenges. The most common problem we faced was that users were not in the habit of checking their SMS inboxes, and some did not even know where their SMS inbox was. To address this particular issue, we did a pilot using WhatsApp to complement the advisory service, sending WhatsApp messages to 1,200 farmers over two months. On average, 76% of users read these messages. This also highlighted how vital ongoing training is to familiarize users with the platform; one-time training is not enough. While we cannot do a perfect comparison with the self-reported reading of SMSes, WhatsApp messages suggest a promising channel for increasing engagement with the service in future programs.

Conclusion

Starting a new program in a new country and on a new continent was challenging but very rewarding. Despite some key team members living outside of Colombia in the initial four months of implementation, we built a strong team during the COVID pandemic and launched a new service that was innovative for PxD in many ways, providing digital extension services through WhatsApp, exploring new ways to build trust in a post-conflict environment, navigating poor connectivity, and prioritizing content in the context of a new country. We learned how to implement a sustainable and impactful program in Colombia and are now working towards new opportunities and partnerships in Colombia and the wider Latin America region. We hope to soon leverage all of our knowledge and experience from this project and continue to grow our presence in this part of the world.

Accurate, medium-range weather forecasting information can help mitigate smallholder farmers’ exposure to climate-related risks. PxD is in the process of launching new products to assist smallholder farmers to make more informed and timely decisions based on weather information. In this post, we outline the contours of our exploratory research to integrate weather forecasts into Coffee Krishi Taranga (CKT), our existing digital advisory service for small coffee farmers in India.

Coffee is a notoriously fickle crop. For example, heavy rainfall can damage crops, result in premature fruit-drop, increase the incidence of pests, and wash away fertilizer with negative implications for plant nutrient levels. Increasing weather variability and the incidence of extreme weather events associated with climate change will have significant negative effects on coffee producers. Given the sensitivity of the crop — and yields — to fluctuations in the weather, coffee farmers are likely to derive meaningful benefits from accurate and timely weather forecasts. Insights from our CKT learning agenda will be used to inform the design of a larger evaluation of the weather-integrated service and to scale an enhanced service to over 150,000 coffee farmers across four Indian states (Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh – an expansion state).

The motivation

PxD delivers CKT in partnership with the Coffee Board of India and with support from the Walmart Foundation. Since 2018, CKT has delivered a two-way interactive voice response (IVR) service with two principal components: an outgoing push call service that provides regular advisory to coffee growers via their mobile phones, and an inbound hotline that farmers can call to access free information services. In April 2022, CKT reached just over 70,000 smallholder coffee farmers in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

More accurate information about medium-term rainfall — with a lead time of up to 15 days — will enable farmers to make informed decisions about applying nitrogen fertilizer and increase the likelihood that they apply this input during dry spells to reduce run-off and leaching. Similarly, if farmers are alerted to impending heavy rain, they can leverage this information to alter harvesting times or take other precautionary measures to protect crops and insulate yields.

Speaking to farmers to inform design and process

In interviews conducted with coffee growers in August 20211 Described further in an earlier blog post that outlined findings from the landscape analysis of coffee production in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh relating to sustainability, market linkages, and gender., only 16% of respondents reported accessing forecasts (N=73). Integrating weather information into CKT’s existing services will broadcast weather forecasts to farmers tailored to their specific contexts and complement these forecasts with agronomist-designed advice. Exploratory and pilot research will be implemented between May and December 2022 in three important coffee-growing districts in Karnataka: Chikmagalur, Hassan, and Kodagu.

Studies conducted in other contexts find that farmers form subjective expectations about upcoming weather events based on various factors, including their past experiences, local rules of thumb, existing forecast information, the costs and benefits of acquiring such information, and perceptions about how relevant weather-related risk is to their incomes2As demonstrated in Giné, X., Townsend, R.M., & Vickery, J. (2015). “Forecasting When it Matters: Evidence from Semi-Arid India.” Working Paper.. These expectations inform behavior over the course of the coffee crop cycle as farmers make decisions relating to input and investment choices, the timing of activities, and so on. The sum of these decisions, in turn, influences outcomes that farmers (as well as researchers and practitioners) are interested in – notably plant health, yields, costs, and profits. The goal of this research is to understand each of these elements through measurement and service pilots, A/B tests, qualitative interviews, and in-person workshops with farmers, agronomists, and extension agents.

Coffee laborers having lunch on a coffee farm.

Iterating relevant service design and a weather service at scale

Commencing in May 2022, we will conduct multiple rounds of in-depth qualitative interviews with men and women coffee farmers. The sample will include farmers working a range of landholding sizes and will include both smartphone and feature-phone owners. The objective of the first set of interviews is to better understand how coffee farmers make decisions relating to the timing of agronomist-identified, weather-dependent coffee activities: fertilizer and lime application, coffee pruning, shade regulation, and harvesting. We hope to identify how weather fits into these decisions and what other factors influence the timing of these activities. If other limiting factors (such as the availability of an input) impact timing to a greater extent than the weather, forecast information with short lead times may not help farmers optimally time their practices without access to complementary inputs or information. These interviews will also help us identify how farmers interpret weather forecasts they already have access to, what impact incorrect forecasts have on their activities and on their trust in forecasts and the extent to which farmers discuss their expectations of upcoming weather with other members of their communities.

As detailed in previous blog posts about our weather-related work, PxD is partnering with leading private forecast provider CFAN (Climate Forecast Applications Network) to develop calibrated custom forecasts. Using weather forecasts from CFAN provides access to a continuous stream of information, which includes the numerical quantity of a rainfall event being forecast, numerical probabilities associated with a forecasted weather event, and error margins on the quantity of rainfall forecast for each of the upcoming 15 days3Read more about our collaboration in this previous blog post. Building on the first set of qualitative interviews, we plan to assess (1) whether farmers comprehend and have an appetite for probabilistic and uncertain information; (2) whether specific forecast attributes or lead times meaningfully change farmers’ expectations of upcoming weather; and (3) which combinations of attributes and lead times aid decision-making for each weather-dependent activity. We plan to gauge farmers’ understanding of probabilities and uncertainty in a second set of in-person interviews to whittle down the forecast formats that will be most useful in this context.

PxD facilitated Interviews with coffee growers.

Coffee farmers in a subset of villages in our three study districts will then be invited to participate in in-person workshops, where they will interact with different forecasting formats. The workshop will be in the form of a ‘lab-in-the-field experiment’, where participants engage with an interactive platform that presents weather forecasts together with incentivized agricultural decision-making scenarios. Utilizing participants’ decisions on the platform, an ‘in-scenario’ weather ‘realization’ will be simulated, allowing participants to accrue a higher payoff for a ‘better’ decision. The best-performing forecast will accrue the highest cumulative payoff across participants and will inform our understanding of which forecast formats most effectively aid decision-making. The ‘best-performing’ customized-to-context weather forecast will then be piloted in the field among a sample of existing CKT users to evaluate whether it improves decision-making in a real-world setting.

Delivering an effective weather-based advisory service via mobile phone also requires that we ensure that users engage with and use the information being delivered. To this end, we plan to run A/B tests to optimize the frequency with which weather forecasts are delivered, the length of messages, and other service features.

We are optimistic about the utility of weather forecasting information and its potential impact on smallholder farmers — and their productivity — as they make what we hope will be more informed decisions. We are excited to deploy this information and make it actionable for smallholder coffee producers on our CKT service. Watch this space!

Make an Impact Today