Punjab means “five rivers”, and those five rivers are the reason that the Punjab region in Pakistan is the country’s bread basket. Tomoko and I were in Punjab last week visiting the PxD Pakistan country team. As many of you will know, PxD in Pakistan is housed within a local economics research institute, CERP, a partnership that has enabled us to be more effective and flexible.

This week much of our attention has been on smallholder rice production. The staple food in Pakistan is of course wheat (for roti), but rice is a major crop for both domestic consumption and export. (We were in town at the same time as the IMF delegation, negotiating a package of macroeconomic reforms to stabilise the economy, so those export earnings are important right now).

Punjab is famous for its basmati rice, a variety much prized for its aroma, fluffiness and grain length. It is very popular in traditional dishes like biryani and pulau. We visited Kala Shah Kaku Rice Research Institute, established in 1926, where basmati rice varieties have been developed since the 1930s. Farmers in Pakistan typically grow wheat in the Rabi season and then many grow rice in the Kharif season, especially in the basmati belt in Punjab. The yield of basmati rice is around half as much per hectare as hybrid rice varieties, but it sells for around twice the price, so generating similar revenues and broadly similar net income per hectare. (An exciting development on the horizon is the prospect of hybrid basmati rice that may have a much higher yield while retaining much of the quality for which basmati rice is famous.)

Many of the people we met were keen to stress that Pakistan, rather than India, is the home of basmati rice. I’d be very glad if the rivalry between these two great nations were confined to arguing about the origin of basmati rice and, far more importantly, their relative prowess in cricket.

Pakistan’s farmers produce on average around 4 tonnes of rice per hectare, about the same as in India. In China, the yield is 7 tonnes per hectare and in Australia 10 tonnes per hectare. The yield gap (that is, the gap between what farmers produce and what they could produce with the land and other inputs available to them) is estimated to be about 50% – about 3.5 tonnes per hectare – for basmati rice, and closer to 60% – 6 tonnes per hectare – for the higher yield but lower price varieties. In other words, farmers could, in principle, at least double their yields. So what is holding them back?

You would expect farmers to be more interested in increasing their profit than their yield, so one possible explanation – in theory – could be that the additional inputs are too costly, and the value of the extra output does not justify the investment. In that case, it would be rational for farmers not to increase their output this way. But that doesn’t seem to be the problem. The additional cost of the recommended inputs, at market prices, is small relative to the price that basmati farmers could get for the roughly extra 3-4 tonnes per hectare that they could be producing. Despite extra input costs, the extra yield on this scale would lead to much higher profits – perhaps multiples of profits now being earned. If you are doing only a little better than breaking even, then moving to a reasonable surplus could mean a transformational increase in net income.

So what is getting in the way? We spent two days in villages outside Lahore talking to farmers, extension agents, and private and public sector experts to try to get a better picture.

My main take-away is that it seems that expensive credit for agricultural inputs and low prices paid by middlemen (called aahrtis) leaves farmers with little surplus. Farmers are unwilling to take on a large, expensive debt which – if the harvest is bad – they may not be able to repay, especially when they know that a big chunk of any profit, if the harvest is good, will go to the middleman. So they stick to limited use of inputs, which gives them lower yields and less debt and thus lower risk. Thus it is the cost of credit, and the associated risk, rather than the cost of the inputs themselves, that stops them from investing more.

I’m conscious that we met farmers close to Lahore, who are relatively well-off, and who are already in contact with extension services. So we should be careful about drawing too many conclusions. Based on these few conversations with an atypical group of farmers, I find it hard to convince myself that there are very many practices that farmers could adopt that they do not already know about. That said, there may be some value to encouraging practices that cost the farmer little or nothing to implement – or which save inputs such as using the right amount of urea – for example by issuing timely reminders. But it looks as if the larger gains would come if we could find a way to reduce the risk of increased investment in inputs, reduce the cost of credit, provide high-resolution weather information, or perhaps improve planning and coordination in the use of scarce machinery or casual labour.

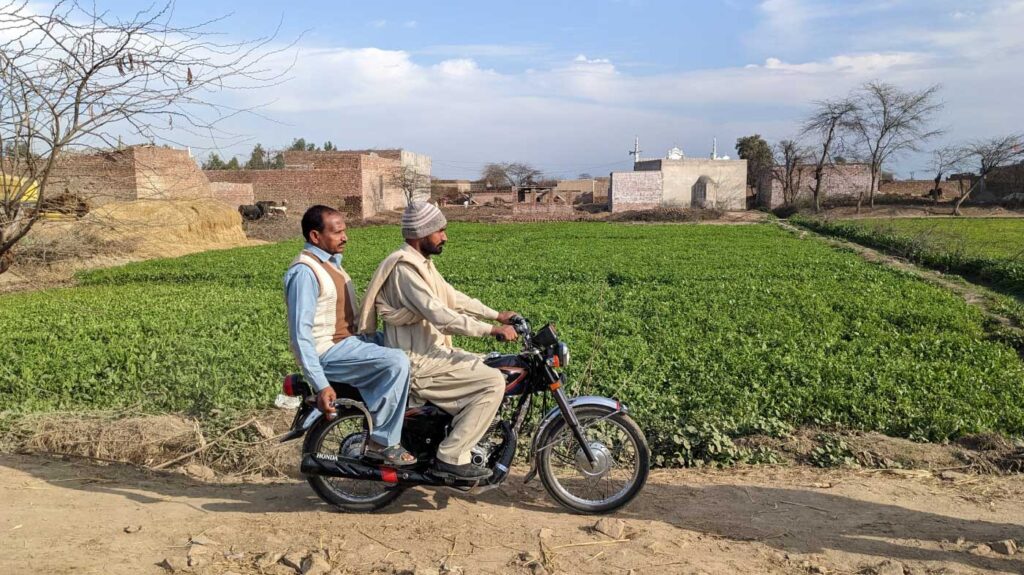

It is harder to notice what is missing than what is in front of you. As you may see from the photos, we did not meet any women farmers. We met a female scientist at the rice institute, but everyone else we spoke to was a man. In every conversation, farmers were routinely and unthinkingly referred to as “he”. Yet we know that women provide a substantial part of labour in agriculture, and are hugely affected by all the decisions that are made. If we want to understand what it would take for farmers to adopt practices that would increase their yield and their incomes, we are likely to learn a lot by talking to women too.

I leave Pakistan optimistic but uncertain. Optimistic because the opportunities are huge for large increases in yield and potentially transformative increases in farmer incomes. The constraints are real, but there may be solutions that have a low marginal cost per farmer and so would be hugely cost-effective at scale. Uncertain because we do not yet have enough information to arrive at robust ideas for higher-impact services that we could design and test.

I want to thank Adeel, and all the team, for giving up so much of their time and energy to host us – including taking us to the old Walled City of Lahore to have dinner overlooking the famous Badshahi Mosque (Mosque of Kings) and the Lahore Fort (Shahi Qila in Urdu), an ancient citadel of the Mughal Empire. I look forward to returning to Pakistan soon and hope to combine my next trip with some tourism in your beautiful country.

When disease and a heatwave, followed by devastating floods ravaged Pakistan’s Punjab province, PxD’s LMAFRP digital information service, which we implement in partnership with the Rural Community Development Society (RCDS) with support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), assisted women livestock farmers navigate new and unprecedented challenges. This International Day of Rural Women, we highlight the important role women play in Punjab’s rural farming economy and our work to promote information to enhance more productive and resilient livelihoods.

Introduction

Livestock husbandry and livestock-related products (dairy, meat, leather goods, etc.) constitute an important sub-sector of Pakistan’s agriculture sector: Pakistan is the fourth largest milk-producing country in the world1Sattar, Abdul, “Milk Production in Pakistan” PIDE Blog, pide.org.pk/blog/milk-production-in-pakistan , and the share of livestock products in the generation of foreign exchange is approximately 13%2Government of the Punjab, “Livestock Contribution” , livestock.punjab.gov.pk/livestock-contribution. As is the case in many smallholder economies, in Pakistan, women are largely responsible for the care of livestock and for the production of many livestock-related products, particularly dairy3Ibid..

In rural areas, livestock plays an outsize role in livelihoods, with the Punjab provincial government estimating that “livestock is an integral part (30-40%) of the livelihood of about 30 to 35 million rural farmers”4Ibid.. Livestock-related products, such as butter, eggs, meat, and animal fats (oils), contribute important nutrients for all households – rural and urban – and play a critical role in meeting the nutritional needs of rural children. Further, livestock contribute an important source of continuous income which can sustain poor rural households between seasonal crop-related revenues, and insulate them from shocks5Ahmad, Tusawar Iftikhar and Tanwir, Farooq, “Factors Affecting Women’s Participation in Livestock Management Activities: A Case of Punjab-Pakistan”, mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93312/1/MPRA_paper_93312.pdf..

For these reasons and more, supporting the development and improvement of livestock farming can have a considerable impact on improving the livelihoods of Pakistan’s rural population, and can impact the livelihoods and status of rural women. We believe significant gains can accrue to rural farming families through the promotion of best practices to women. Improved practices can improve yields and minimize losses, leading to increases in income from livestock farming.

Many rural women are unaware of best practices that can optimize outputs associated with livestock, and access to information and economic opportunities can be constrained by cultural and geographic barriers. As documented elsewhere on this blog, digital extension services offer cost-effective and easily scalable solutions with very low marginal costs. In rural Pakistan, where many women rarely leave their homesteads, the portability of digital information offers additional advantages for navigating geographically and culturally hard-to-reach spaces.

Geographic and cultural constraints to attending in-person RCDS livestock training sessions were exacerbated by social distancing introduced to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. RCDS’s in-person activities were suspended in the initial months of the pandemic, but the utility of advisory information increased as rural households navigated new challenges in a time of escalated economic stress. It was at this time that RCDS and PxD initiated a partnership to deliver advice to livestock-rearing women in rural regions of Punjab province in Pakistan. This collaboration, supported by IFAD, provides customized and actionable digital information to livestock-rearing women. Combining PxD’s experience in delivering digital extension services to Punjabi farmers and RCDS’s extensive local knowledge and expertise, the service draws on demographic insights, and cultural practices to deliver information that is accessible, comprehensible, and actionable for recipients.

The resultant digital advisory service has proven to be an effective, cost-efficient, and scalable supplement to in-person training, and is now extended in the absence of COVID-19-related social-distancing constraints. The service demonstrated new advantages when unfamiliar disease- and climate-related threats subsequently impacted rural households.

The Service

RCDS’s experience and local trust in their services have been integral to the success of the initiative. Over the past two decades, RCDS has partnered with local, federal, and international institutions to build a significant rural network to promote and implement development programs to assist poverty-stricken segments of society in rural areas of Pakistan.

Advisory content was developed in partnership with local livestock consultants who were well-informed about local livestock issues and output-increasing best practices. The advisory information distributed by the service covers a wide array of topics, including disease identification, information about and access to vaccinations, disease prevention and remedies, practices to increase milk yields, and guidance on protecting livestock against climate-related shocks.

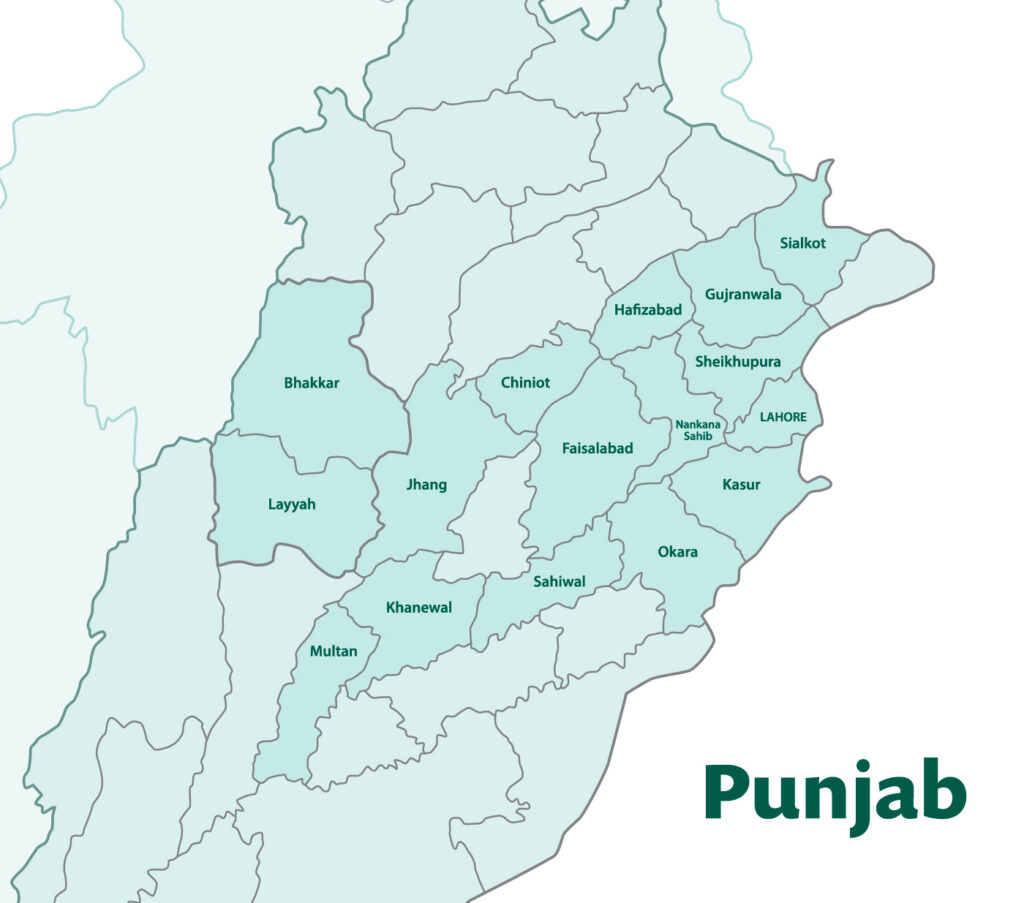

After conducting a baseline survey to systematically understand the informational needs of women farmers in four districts in Punjab, and the development of advisory information, PxD piloted digital services among 3,160 rural women associated with RCDS. The four districts, in which the pilot was concentrated, are among the poorest districts of Punjab, all of which are located in the south of the province. Given the success of the initial pilot, the service has subsequently been expanded to more than 50,000 livestock-rearing women in 16 rural districts of Punjab.

One of the key components that PxD assessed during the initiative was the extent of knowledge retention by participating women after they received the advisory. Pilot testing in the early stages showed that the advisory information was not only useful but was also retained for a significant period after it was delivered.

RCDS maintains a dataset of women who have either attended in-person sessions of livestock advisory or shown an interest in livestock advisory or have taken a microfinance loan for livestock farming. This data, and its quality, were instrumental in helping PxD deliver the advisory directly to the women via their phones. Furthermore, the data also contained the districts in which each woman resided. This was used to help decide in which of the two local languages – Punjabi and Saraiki – the advisory would be conveyed.

Advisory information is delivered through a voice call. A text message is sent 24 hours before the call to alert users that they should expect a call the next day. This is done to ensure that the advisory is received by women. A barrier highlighted by the baseline survey was limited access to mobile phones on the part of women in the region. Cultural and financial constraints make it far more likely that men have primary access to cell phones. Hence, the time allotted for the voice calls is set at a specific hour in the evening, so that the call is received in the evening when the family is no longer busy with agricultural activities, men are more likely to be home, and when family members can collectively listen to the advisory in their homes.

The voice call has local cultural music layered in the background, to assist the participant in developing trust in and comfort with the message. The information is delivered in the local dialect – Punjabi or Saraiki – to enhance understanding of and familiarity with the recorded message. Further, listeners are told that the advisory is from RCDS since it is well-known as a trusted organization in these regions. As a general protocol, to improve pick-up rates when the voice call is unanswered, another call is placed after a 15 to 30-minute interval.

Lumpy Skin Disease

A significant advantage of digital extension is the ability to send timeous information. This is particularly valuable to address and prevent viral diseases that can have a drastically negative impact on the well-being of the livestock.

In April 2022, Pakistan saw a viral outbreak of lumpy skin disease in cattle. The disease was transmitted between cattle via blood-feeding insects. The disease has a high virulence and fatality rate and killed thousands of cattle in the country.

A significant hurdle that seriously hindered timely prevention and actions to curtail the impacts of the infestation was the lack of baseline knowledge and awareness of the disease. Moreover, misinformation was rife, with misplaced rumors about negative effects of vaccines abounding. Many people mistakenly believed that it was the vaccines that were causing deaths among animals, when animals that had died were either already infected with lumpy skin disease, or were generally sick and should not have been vaccinated at the time.

Understanding these knowledge gaps, PxD and RCDS collaborated to provide timely information about the infestation. Initial infections were observed in the southern part of the country and slowly spread north towards Punjab province, where our users reside. PxD started providing information about lumpy skin before the disease had become widespread in the province.

Our farmer-users were given information about the disease and its virulence, how it is spread, and traditional preventative measures. Following that, to increase the survival rate of infected cattle, users of the service were advised to vaccinate their cattle as soon as vaccines became available. Participants were also informed about how to identify early signs of the disease on the animal.

Anecdotal feedback received by RCDS in the field suggests that the messages were very useful. Users with whom PxD surveyed reported that in many instances they were able to avoid fatal infections in their animals due to timely vaccines, even if their animals did get infected.

The Floods

In the summer of 2022, Pakistan witnessed firsthand the severe impacts of climate change. In March and April, the country experienced a crippling heat wave, followed by a record-breaking monsoon season in Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan spanning June, July, and August. An unparalleled monsoon, coupled with unprecedented melting of glaciers in the north due to the initial heatwave, led to extreme flooding in rivers that flow from the north of Pakistan to the south. The floods are estimated to have impacted at least one-third of Pakistan, including the livelihoods of 33 million people.

Prior to the floods, the extreme heat waves had contributed to a general belief that floods were imminent. To counter the threat, the PxD team in Pakistan worked with RCDS to preemptively identify areas prone to flooding, and prepare advisory messages with useful information about managing floods, and adaptive strategies to protect assets and livelihoods.

A major problem with livestock is their slow mobilization, making them and their rearers prone to becoming flood victims. Timely warnings and regular updates via voice call advisory messages provided participants with information for ensuring the safety of their livestock during the floods. PxD and RCDS made use of their existing program to deliver instructions, warnings, measures, and assistance via voice call messages, to inform participating women and their families about floods and ways to protect themselves and their livestock.

Meeting today’s challenges

The advisory service designed by PxD, and delivered in partnership with RCDS, provided an effective method to deliver timely information to livestock farmers. Due to its effectiveness in the regions where it was being delivered, the advisory service was extended to address other unforeseen challenges, such as the virulent lumpy skin disease, and flooding.

In addition, our project has demonstrated the core strengths of digital communication: it is cost-effective, scalable, and capable of reaching regions and communities that are disconnected or hard to access due to difficult terrain, long distances, or cultural constraints.

Our advisory content was designed to deliver information in a manner that does not require the recipient to have prior knowledge, or education to understand the subject. The use of familiar dialects and carefully crafted messages made the information accessible, easy to understand, and ultimately very effective.

PxD aims to further extend the benefits of digital communication to support other low-cost interventions among rural communities of Pakistan. More specifically, feedback received from users has prompted PxD to further our partnership with RCDS to envisage interventions to support digital veterinary services. We are motivated to continue to harness the power of digital communication to facilitate more productive and resilient livelihoods in rural communities of Pakistan.

Agricultural livelihoods predominate among the rural population of Ethiopia to such an extent that agriculture makes up 32.5% of the country’s GDP (2020/21) and accounts for 63.5% of employment (2021). Despite the importance of the sector, agriculture confronts a number of challenges. In recent decades the development of yield-enhancing technologies with the potential to improve smallholders’ livelihoods has excited development practitioners, yet many of these innovations have not had the desired impact. A critical challenge for smallholder farmers is limited access to improved technologies and information. Digital and other technological innovations have created new opportunities to provide and deliver tailored information to farmers. To exploit this opportunity, Precision Development (PxD) is implementing a model to deliver personalized agricultural advice to farmers via their mobile phones.

In October 2019, PxD Ethiopia and Digital Green launched a five-year project entitled Digital Agricultural Advisory Services (DAAS) with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). The project aims to enhance the digital ecosystem of Ethiopia by strengthening existing digital advisory services, establish a new technology platform (FarmStack) to enable actors to more seamlessly share data, and – through the platform – catalyze the activities of actors across the ecosystem.

PxD alleviates information poverty by delivering personalized information to users. By providing actionable information and advice, in the right way and at the right time, we enable farmers to make informed decisions that enhance their livelihoods and productivity. In the dairy cattle context, the optimal realization of this vision would be to provide customized advisory services targeting each farmer and each cow. Obtaining data and integrating data optimally are critical to achieving these ends.

Given the availability of datasets from multiple initiatives in the country, and the potential of data integration underpinning value-added services, the project targeted the development of exemplary use cases. These use cases showcase the value of data and content integration, and highlight their potential to enhance the value of existing agricultural advisory services. To identify the most promising interventions, we mapped existing data and content ecosystems in the country and explored opportunities in the Ethiopian dairy sector for creating value-added services through more efficient data sharing, data integration, big data analytics, and targeted service delivery. The team identified key stakeholders, content gaps, and potential value addition through data and content integration.

The types of data we uncovered through data ecosystem mapping include farmer profiles, plot and herd characteristics, feed resources, farming, and non-farming activities, crop and livestock commodities, gender roles, technology adoption, and issues with performance and capacity. Farm and farmer profile data help inform precise development interventions and, by leveraging data from research projects, help service providers make more informed decisions. For example, PxD started disseminating timely messages to dairy farmers to use Artificial Insemination (AI) services when the service is available and at the time when the cow comes to heat. Using ecosystem mapping data, we identified a set of interventions that have the potential to catalyze significant improvements in the dairy sector. These include more efficient breeding and breed improvement, improved feed and feeding management, improved dairy cattle health services, and more effective marketing of dairies and dairy products.

The team was particularly motivated to improve the provision of effective AI services to increase the proportion of crossbred dairy cattle in the country. Currently, crossbreed cattle only account for 2% of the national herd. Increasing the share of crossbred cattle, and reducing the share of indigenous breeds, can improve dairy productivity. However, there are challenges undermining efficient and effective AI service provision in the country, and these challenges contribute to the low level of success of AI service provision. Challenges include capacity gaps among AI technicians, failure to take cows in heat for timely insemination, and unintended mating. Significant problems are similarly evident in feed and feeding management. After identifying gaps in optimal feed utilization for improved dairy productivity, PxD developed use cases for improved feed and feeding management.

PxD is collaborating with the Ethiopian Agricultural Transformation Institute, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Public-Private Partnership for Artificial Insemination Delivery, the Livestock Development Institute, the Netherlands Development Organization, and others, to develop use cases that aim to provide value-added services to farmers, AI technicians, and development agents. By leveraging a human-centered design approach, PxD Ethiopia has developed content to improve the management of AI, cow pregnancy and lactation, and calf rearing. We have disseminated customized advisory content to farmers and AI technicians through Interactive Voice Response (IVR) push calls.

The feedback that we have received from farmers and AI technicians has been encouraging, with a significant number of farm households reporting that they are adopting improved dairy practices. Two rounds of monitoring data confirm the contribution that data-, content-, and service-integration have made to the value-added services created by the project.

In the two-and-a-half years since its inception, the IVR component of the DAAS project has made significant progress. Today we reach 400,000 farmers via the inbound and outbound channels. By the end of 2024, we aim to scale the advisory, which is focused on the most promising practices, to 2.5 million Ethiopian farmers. Because of efficient data sharing and improved analytical capacity, customized and targeted interventions are benefiting farmers who provide information to development partners. Similarly, development partners are leveraging the existing data sources to design interventions that aim to help farmers and reduce redundancy of efforts. Overall, through efficient data sharing, farmers will benefit from the reduced cost of data collection and from targeted interventions.

Precision Development (PxD) recognizes that the informational needs of poor women farmers, and the challenges they confront, are unique. As a consequence, our services must be tailored to reach and be relevant to the needs of women users. Driven largely by the onboarding of women active in livestock-related activities, the number of women farmers active on platforms built by PxD increased by approximately 46% over the course of 2021. This included the onboarding of over 150,000 women farmers to our Ama Krushi (AK) service, which we deliver in partnership with the Government of Odisha, India. As we mark International Women’s Day, we reflect on efforts we have made to improve our understanding of gendered divisions of labor and bargaining power within Odishan smallholder households, and steps we are taking to assist women farmers make more informed decisions.

Scoping work undertaken by PxD suggests that women farmers spend more productive hours on livestock farming than men. However, women farmers disproportionately lack access to mobile phones and, by extension, digitally conveyed information. Perhaps the largest impediment to increased engagement with PxD’s advisory on the part of women farmers is access to information, and patterns of information sharing within households. This could have knock-on effects that undermine women’s productivity and bargaining power within the household. To further understand these dynamics, we explored if sending messages encouraging information sharing within households can assist in breaking this cycle.

The motivation

Gendered roles in livestock farming

In June 2021, we conducted a survey to improve our understanding of gender roles in livestock farming in Odisha. The sample consisted of 5,354 AK farmers who have subscribed to livestock-related advisory, practice cow-rearing, and had received at least one livestock advisory message via the AK service. The sample included equal numbers of male and female users and was stratified by the farmer’s district. Of this sample, we successfully surveyed 1,475 AK farmer users.

We found that, on average, women AK users allocate more time to livestock rearing and household chores than male AK users (Table 1). Relative to male AK users, women spend less time on cropping activities and on other non-livestock-related income-generating activities.

The survey also found that men AK users are significantly more likely to perform—and be the primary decision-maker for—livestock-related tasks that require travel outside of the home. These types of activities include veterinary visits, purchases of livestock-related inputs, selling milk, and sourcing fodder. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to be involved in livestock-related activities performed at home, such as cleaning sheds, feeding, and milking animals. Given the heavy involvement of women farmers in livestock-related activities, it is important that livestock advisory broadcast via our AK service is communicated to women household members if it is to be practical.

Importantly, many income-related improvements in livestock outcomes—such as increasing milk yields and successful breeding—depend on the coordination of multiple tasks performed by both men and women within a household. For example, successful breeding requires the completion and timely sequencing of tasks and processes, including the provision of sufficient nutrition, deworming, heat detection, and accessing artificial insemination (AI) services. To achieve these ends, it is important that livestock advisory reaches both women and men in the household, and that intra-household communication is sufficient to coordinate improved livestock outcomes and household welfare maximization.

Barriers to information for female farmers

Reaching female farmers through mobile phone extension services is challenging as men farmers are more likely to be the primary owners of mobile phones in the household (OECD, 2018; Baroni et. al., 2018). Evidence suggests that women registered as subscribers to PxD’s mobile advisory services have shared access to phones and male partners are the devices’ primary users. PxD uses polling surveys to maintain and improve quality service delivery, and to source feedback from users. Women AK users polled for our May 2021 livestock survey self-reported lower pick-up rates than male respondents. However, actual outbound AK administrative data does not reflect a gendered disjuncture in pick-up rates. An explanation of this could be that the household member who picked up the phone when an AK call was placed to a women farmer was not the registered woman user. Similarly, during this gender survey in Odisha, we asked the respondent who picked up the phone if they were the registered AK user. In the case of registered women AK users, someone else picked up the call 12% of the time, compared to only 5% in the case of registered men AK users. This difference is statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that when a phone is being shared, registered users that are women have less time with the phone than men. Given the greater engagement of women in livestock-related activities, this gendered barrier in mobile phone extension services is a significant challenge.

To gather more evidence on AK users’ individual access to mobile phones, we asked about a quarter of the AK users in the Gender Scoping Survey (n=370) about their typical access to mobile phones between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m. every day. Women AK users reported less availability at all times of the day (Figure 1). However, the difference is only statistically significant at the 10% level for the 3 p.m. to 4 p.m. period (both in the full sample and the married-only sample). Due to the smaller sample size, we may be underpowered to detect other differences.

Figure 1: Gender differences in individual access to phone

Interestingly, when we restrict the analysis to household heads only, women report higher average access to their mobile phones than men. The Gender Scoping Survey finds that the time-use patterns of women heads of households closely follow those of men heads of households (Table A1), there are a few possible reasons for this deviation in self-reported access to mobile phones. A possibility is that male heads of households are more likely to share their phones with their spouses or children. By contrast, the Gender Scoping Survey found that women heads of household are typically unmarried (or widowed, separated, or divorced) and therefore may not need to share their phones as much as men heads of household.

Consistent with the evidence above, the Gender Scoping Survey finds that men AK users are significantly more likely to cite Ama Krushi as a primary source of livestock information than women AK users (Table 2), while the polling survey finds that women AK users are significantly less likely to answer knowledge questions based on livestock advisory sent in the month preceding the survey correctly.

Importantly, AK users seldom cite their spouses as a source of livestock information or as someone they discuss new livestock information with, a gap in intra-household information transfer that PxD could potentially influence. Improving intra-household communication can potentially increase the reach of PxD’s advisory to existing registered women AK users who may not be picking up the outbound advisory, but also extend the reach of our advisory to the wives and women children of men registered as AK users on the livestock service.

Adoption: Individual vs joint access to information

To better understand intra-household dynamics of information transmission and adoption, we asked respondents to the Gender Scoping Survey if they find it easy to convince their spouses to adopt new livestock practices when they receive such information. Of the respondents, 76% replied yes to this question, and we found no significant differences by gender. This percentage increased to 90% when we asked if listening to the advisory jointly with their spouses on the phone’s speaker would make it easier for them to adopt the recommended practices. A gendered analysis of this increase did not detect a statistically significant difference between men and women users.

Therefore, we find suggestive evidence that getting livestock recommendations to female farmers is the primary barrier to increasing the benefits accruing to our digital advisory. When women farmers receive advisory, they may be just as likely to influence adoption decisions as men farmers. Additionally, increasing the shared knowledge of the spouses has a greater potential to increase adoption rates than individual access to information.

Calibrating solutions

The phone’s speaker

One possible solution to reach more women farmers and promote information sharing among spouses is to encourage respondents who pick up advisory calls to use their phones’ speakers to listen to the advisory with other household members. We wanted to pilot a nudge to male livestock farmers to listen to advisory messages with their speakerphone turned on with other household members engaged in livestock-related activities. However, we first needed to know if farmers could use their phone’s speaker. We conducted a speakerphone feasibility survey to understand:

- Whether farmers can use their phone’s speaker by themselves.?

- If not, can we deliver simple instructions during the phone call so that farmers can use the phone’s speaker?

- Whether we need to build in a time allowance for farmers to activate their speaker and listen to advisory with their household members.? If so, then how much time?

- Whether farmers are willing to use their phone’s speaker and listen to the advisory with other household members.?

Of the 90 respondents who consented to the survey, 76.67% could turn on their phone’s speaker without any instructions (67.92% of feature phone users and 89.19% of smartphone users). Following simple instructions on how to use their speaker, 84.44% of respondents could do so. Overall, 89.19% of respondents were able to turn on their phone’s speaker within 10 seconds of being asked to do so, and of those, 96.2% were willing to use their phone’s speaker to listen to future AK advisory with their family members. As a consequence we are confident there are no large technical or aspirational barriers to adopting the nudge and we moved to pilot it in different forms.

Assessing potential interventions

These results encouraged us to test nudges in three ways for one month:

- A separate IVR nudge asking users to call into our inbound service for joint-listening over their speakerphone (n=600);

- A text 20 minutes before the weekly livestock advisory asking them to turn on their phone’s speaker and listen to the advisory with members of the household involved in livestock-related activities (n=500);

- An additional script at the start of the weekly livestock outbound with the same nudge as in Method 2 (n=500).

All the nudges were sent between 6 and 8 pm based on the findings on joint availability in the gender survey. Before implementing an A/B test to measure the effectiveness of these interventions, we conducted small pilots to select the most promising methods.

In the pilot, we did not find that nudging farmers to use the inbound services (Method 1) was very successful. We sent a nudge call to 600 farmers, asking them to dial a toll-free number to listen to the livestock advisory on the speakerphone with their family. A total of 12 people (and 14 total calls) dialed into the service within a week of the nudge, but none accessed the feature to listen to the livestock advisory. While this does not eliminate the possibility that nudged farmers discussed the call’s content with their spouses, we did not pursue this method to achieve the specific objective of joint listening.

For farmers who were nudged through an SMS (Method 2), using a short survey, we found that only 4% of respondents recalled the nudge’s content (n=126). We concluded that this method was unlikely to translate into increased joint-listening or improved knowledge and adoption.

Using another short survey, we found that farmers who were nudged in the introduction of the weekly livestock outbound advisory (Method 3) were 22 percentage points more likely to report having listened to the advisory message jointly with household members than those who received the regular outbound advisory (ntreatment = 61; ncontrol=45). As this method showed the most promise, we conducted an A/B test deploying it to 17,000 farmers over ten weeks starting in late October. We are currently reviewing data from this test and will share the learnings when they are available.

The authors would like to thank Qi Xue, PxD Intern, who offered valuable assistance in executing the surveys and preliminary analysis underpinning this post, as well as Niriksha Shetty, Tomoko Harigaya, and Otini Mpinganjira for their insights and guidance.

Appendix:

Women play important roles in smallholder dairy production. As PxD prepares to roll out a dairy advisory initiative in Kenya, we conducted a gender survey to better understand the division of labor within households. In this post, the second of a two-part series, Sam Strimling, Research Associate, presents an analysis of the results. The first post laid out the importance of understanding the specific needs of women in designing effective service delivery for women.

In many smallholder households, labor relating to the tending of livestock – particularly dairy animal husbandry and dairy production – is derived disproportionately from women. This culturally entrenched division of labor has direct implications for PxD as we expand into supporting dairy farming activities and seek to target our digital advisory services appropriately.

There is a plethora of evidence – much of it detailed in the excellent book, Invisible Women, by Caroline Criado Pérez – of service providers who failed to understand women’s specific needs and preferences and thus designed inferior products. Providers of digital advisory services are no exception to this disappointing phenomenon.

As PxD prepares to roll out a dairy advisory initiative in Kenya, we considered it a top priority to conduct a gender survey to better understand the roles played by each household member with a focus on tasks performed, decision-making, and financial agency. The results of this survey will be used to inform the dairy content we are developing as part of an upcoming randomized controlled trial (RCT) we are implementing in partnership with several dairy cooperatives across different regions in Kenya. We will use the results of the survey to inform the type of content we write, as well as how and to whom we deliver it.

As detailed in a previous blog post about the survey, the PxD Kenya team used a novel and rich dataset to inform survey design. In addition to gaining insights into the roles played by different members of the household, we also sought to better understand the technical and analytical abilities of each respondent, as well as perceived technical knowledge for each household member. Finally, we used methods from behavioral economics to empirically evaluate trust within the household.

Survey Structure

We started with a total sample of 600 households randomly selected from two dairy cooperatives, in the Rift Valley and Eastern regions. The sample was stratified by geography, milk sales to the dairy, and deductions for purchases from the dairy-affiliated agrovet (in which farmers are able to purchase animal medicines and farming inputs using income from milk).

We called 464 unique respondents, of whom 357 answered at least one call. Respondents who lived with or made decisions with their spouses were asked to provide contact information. Single respondents – many of whom were widows or widowers – were encouraged to complete the survey, but were not asked a series of subjective questions about the degree to which they made decisions or discussed activities with their spouses. Single respondents were also not asked to participate in the public goods game. In total, 114 spousal pairs completed the full survey. These spouses, and their respective households, will be the focus of this post. The demographics of the survey respondents and their households are shown in the table below.

Intra-household dairy roles. At the start of the survey, each respondent was asked to list the members of the household above the age of five, and state their age, gender, and education. The survey enumerators used tablets to record responses that allowed them to capture this information to be used later in the survey. Respondents were then asked to select from this list to indicate which member(s) of the household:

- Practiced crop farming, grazing, fetching water, wage employment [Respondents were specifically asked if they held “a job outside the home.”], schoolwork, childcare, and/or leisure in any given week. Respondents were also asked to indicate the number of hours each selected household member spent on each task in a typical day.

- Practiced various dairy tasks, selected from a list of tasks generated by our Staff Dairy Livestock Expert. For each task selected, respondents were asked to indicate which household member took primary responsibility, and how many minutes this individual typically spent on that task per day. This is the only household roster question for which the respondent was asked to select a single respondent rather than having the option to select multiple members.

- Were knowledgeable about nutrition, artificial insemination, hygiene, disease, and feed and fodder. The respondent was also asked to rank the selected household members in terms of their knowledge on that particular topic.

- Had taken various financial actions, including purchased a personal asset, purchased a productive asset, sold crops on behalf of the household, received payment for crops on behalf of the household, received payment for milk production, and made decisions about spending dairy income.

Analytical ability and dairy knowledge. Respondents were asked to answer a series of scenario-based analytical questions as well as questions to assess technical dairy knowledge on a broad range of topics. We then calculated the percentage of analytical and technical questions the respondent answered correctly.

Subjective assessment of financial agency and cooperation. Respondents were also asked to provide information on their personal knowledge and feelings of financial agency. To assess financial agency, respondents were asked to indicate using a Likert scale the degree to which they discussed finances with their spouse, trusted their spouse’s financial decisions, talked with their spouses about agricultural work, and talked with their spouse about their day generally.

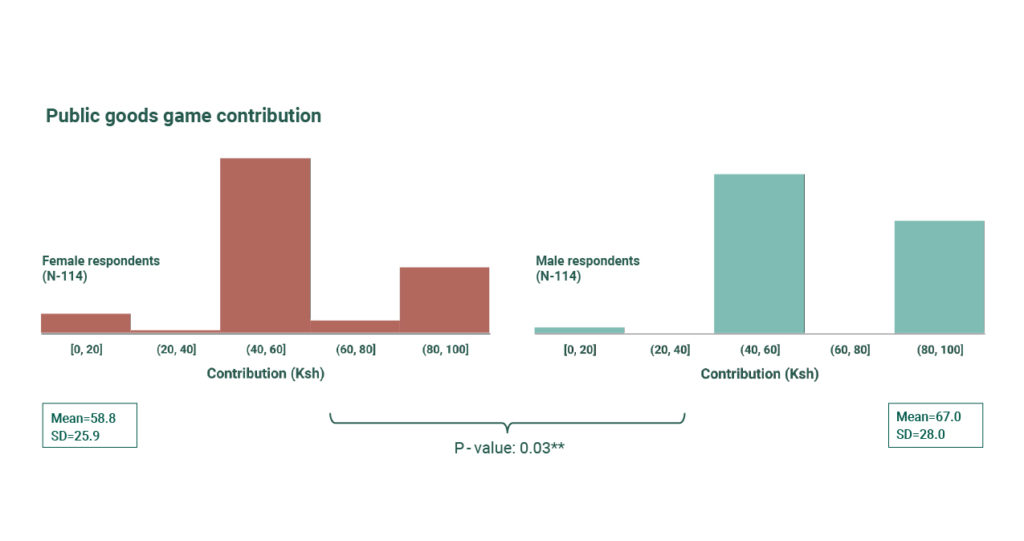

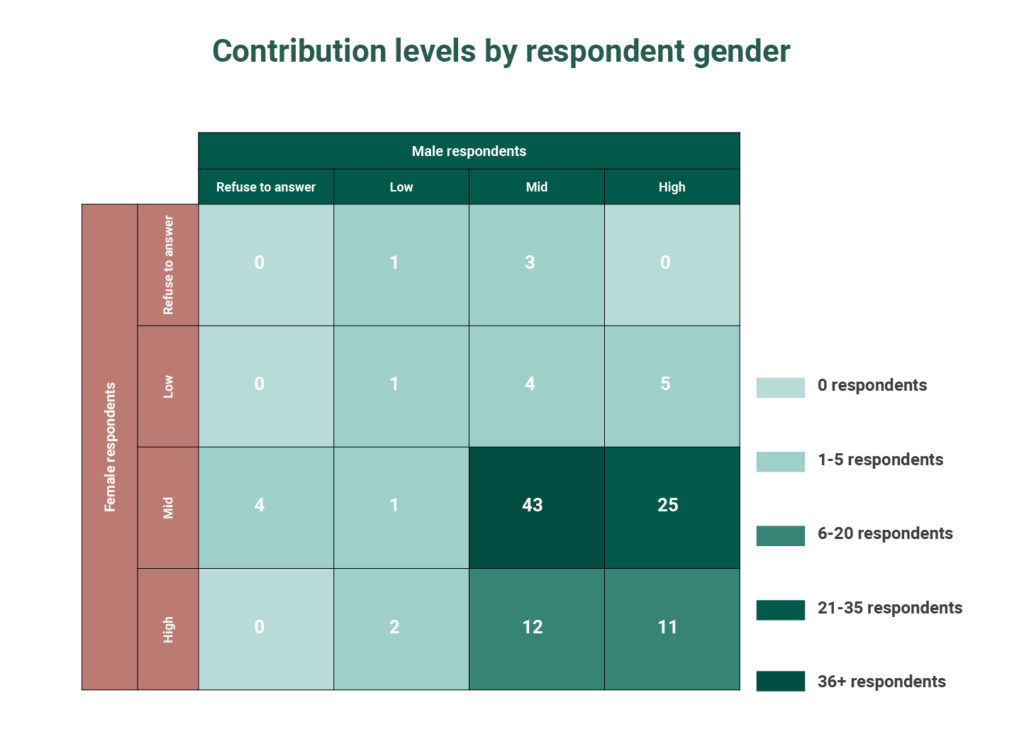

Intra-household cooperation – the public goods game. Finally, all respondents who completed the survey were awarded 100 Ksh (approximately $1) in airtime, and – if their corresponding spouse had also completed the survey – they were invited to increase their earnings by contributing some portion of their earnings into a common account with their spouse. Since the amount contributed to this common account was doubled and then split evenly, the respondent’s contribution could be interpreted as an empirical measurement of cooperation with their spouse.

Information asymmetry. For the 115 households in which we collected information from both spouses, we were able to calculate the degree of coherence in their responses in terms of the intra-household (inter-spousal) correlation coefficient.

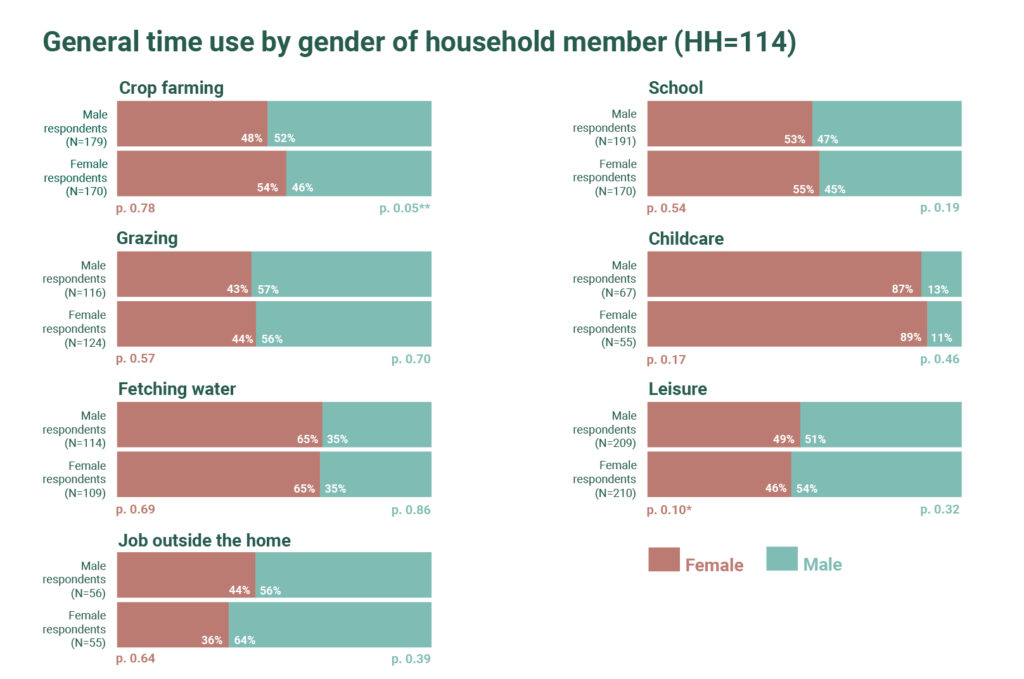

General Time Use & Dairy Tasks

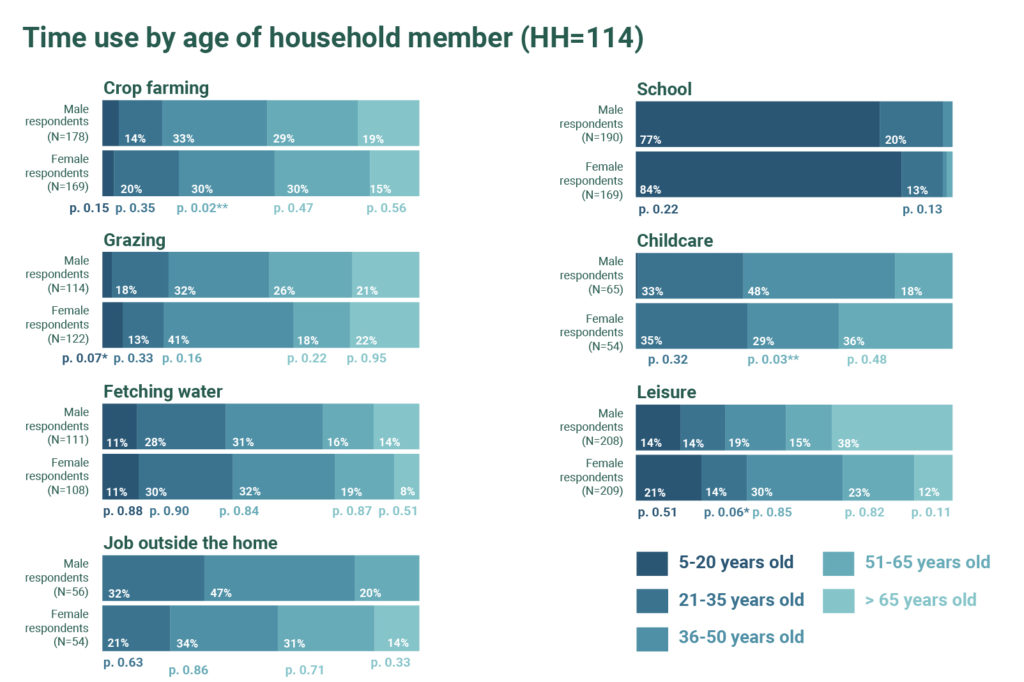

Male and female respondents broadly agreed on the division of labor within the household by gender of household members. We focus our description of intra-household gender-specific roles on the share of time spent by males and females within the household and checked whether men and women respondents generally agree on this proportion. This is presented in Figure 1 below, which organizes respondents’ perceptions by the proportion of hours household members of different genders spend on pre-specified activities within the household (p-values reflect tests of the null that there is no difference in responses across spouses). While male and female respondents differed in their reports of the time spent by gender of the household member, these differences were not significant for any time-use category other than crop farming. In this instance, the difference in perceived hours on task from the perspective of male and female respondents was statistically significant at the 5% level (as demarcated by the p-values next to each bar). In general, respondents of both genders reported that crop farming, grazing, school, and leisure were split nearly evenly by gender. Female household members, however, were reported to spend more time fetching water and engaging in childcare relative to male household members, and male household members were more likely to have a job outside the home.

There was an overall alignment between male and female respondents on the reported activities of different age groups (Figure 2). The overwhelming majority of those in school were aged 5-20, while those aged 26-50 performed the bulk of income-generating labor, including crop farming, tending to grazing animals, and jobs outside the home, as well as tasks culturally associated with “women’s work” (fetching water and childcare). Leisure was fairly equally distributed across age groups.

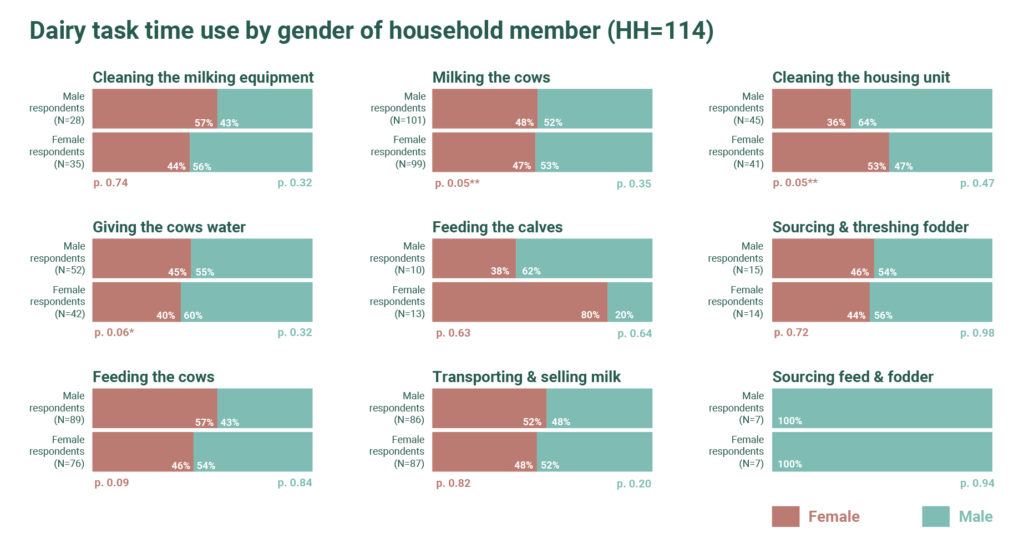

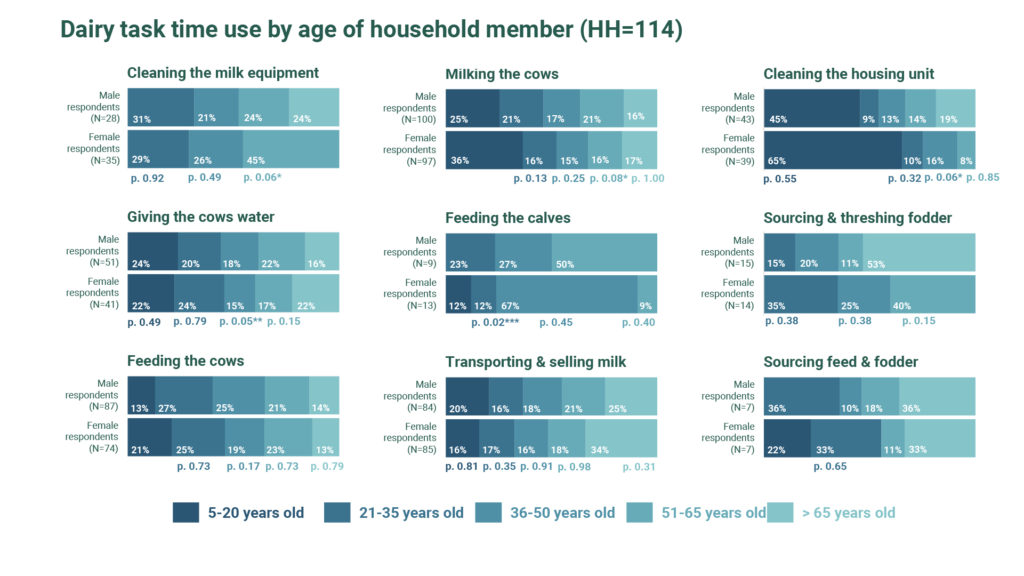

Of the 20 dairy tasks that each respondent was able to select from, nine were selected by respondents in our sample: cleaning the milking equipment, giving the cows water, feeding the cows, milking the cows, feeding the calves, transporting and selling milk, cleaning the housing unit, sourcing and threshing fodder, and sourcing feed and fodder. Figures 3 and 4 below applies the same analysis to these tasks as applied above to the responses on household time use: that is, Figure 3 analyzes the differences in male versus female respondents’ perceptions of household members’ dairy time-use by the gender of the household member, and Figure 4 analyzes this in terms of household member age group.

For most tasks, labor appears to be split fairly evenly by gender. A possible exception to this rule is feeding of calves, which female respondents assert is performed more by women than by men at a ratio of 4:1; men disagree on this, however, which is statistically significant at the 5% level, though the relatively low sample size makes it hard to put too much stock in this comparison. Further analysis could examine whether there is a difference based on a household’s production system. For example, in zero-grazing (or semi-zero-grazing) households, domestic tasks may account for a larger share of household labor, in turn skewing labor allocation toward the purview of women.

In addition to splitting labor by gender, dairy-related labor also appears to be distributed relatively evenly across age groups. The exceptions to this rule are “feeding the calves” and “cleaning the housing unit,” which according to female respondents – but not male respondents – is overwhelmingly performed by younger populations. Though difficult to say conclusively, a possible explanation for this difference in reporting is that female respondents may be more aware of how labor is divided on these tasks, which tend to be domestic in nature.

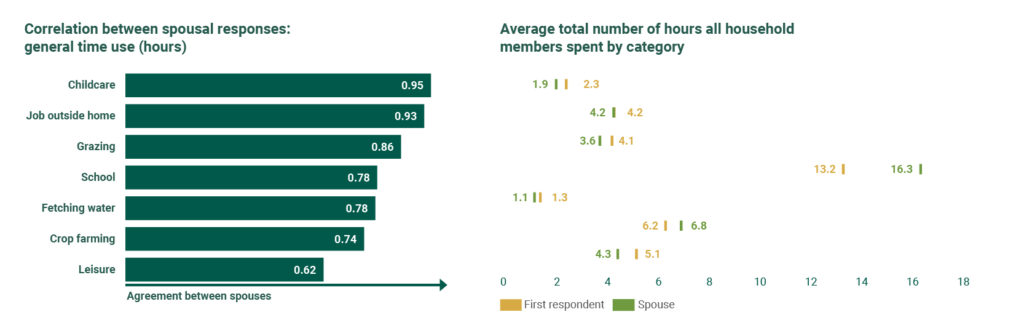

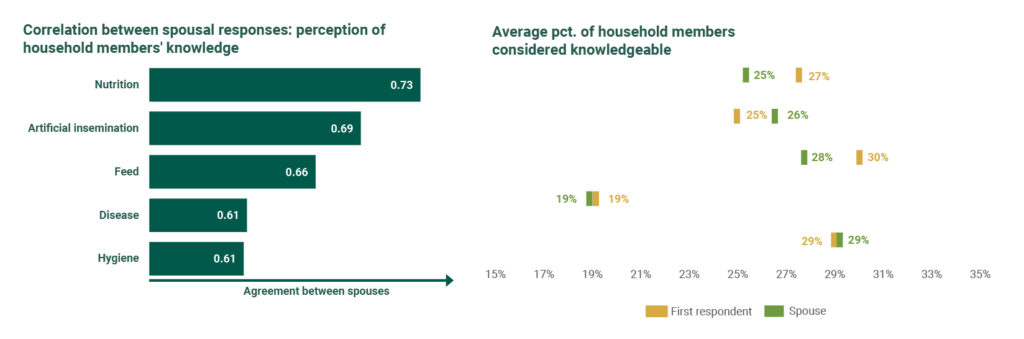

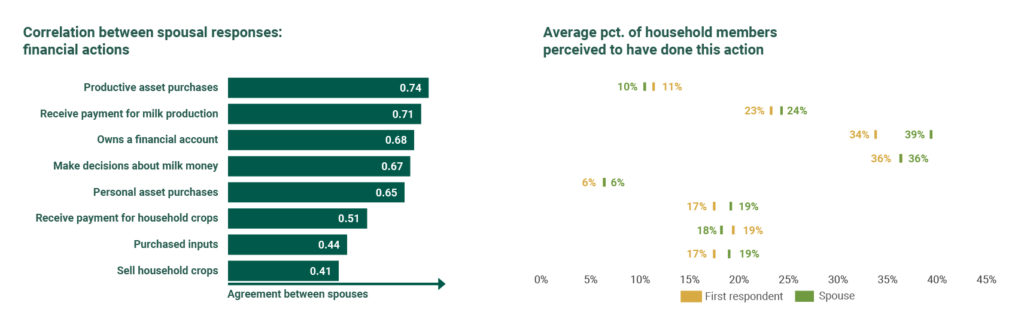

While on average there seems to be a great deal of agreement between spouses in our sample, this does not preclude the possibility of variation in the degree of agreement across households. Figure 5 below displays a measure of within household agreement by calculating the correlation coefficient in the vector of responses provided by women and men respondents in the same household. If, for example, on average, most husband and wife pairs agree on the time spent within the household on childcare, the correlation coefficient will be closer to 1. If they systematically disagree, the correlation coefficient will approach -1. If the correlation coefficient is close to zero, there is no clear agreement between husbands and wives within the same household on how tasks are distributed among household members. In our survey, there was a high degree of correlation between spousal responses for general time-use categories (i.e., crop farming, childcare, leisure, etc.).

Knowledge

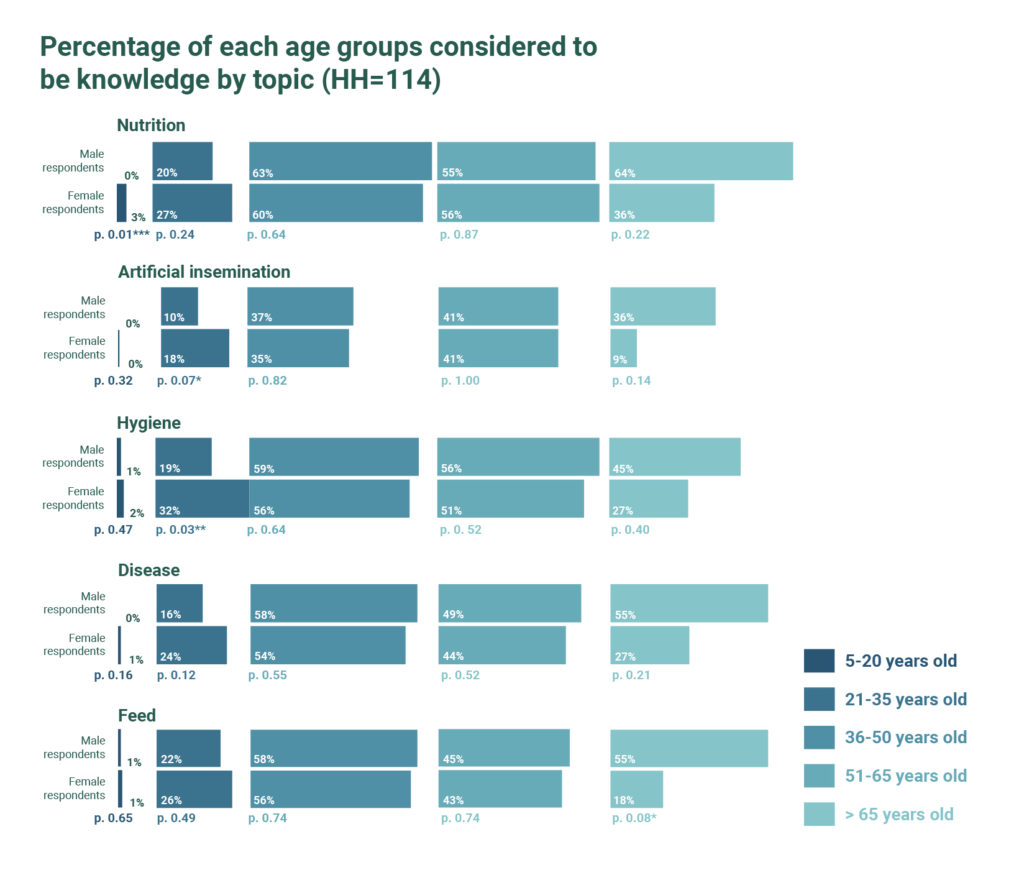

Prior to measuring actual analytical skills and technical knowledge, we asked respondents to subjectively indicate which household members possessed knowledge in five categories: nutrition, artificial insemination, hygiene, disease, and feed. We then calculated the total percentage of individuals within a household perceived to have knowledge on a topic by gender (Figure 6) and age group (Figure 7).

Across all categories, both male and female respondents perceived male household members to be more knowledgeable; there was broad intra-household agreement on knowledge perceptions as well (see Figure 8). Interestingly, male household members were judged to be especially knowledgeable in categories such as disease and artificial insemination; this was particularly true in the eyes of male respondents, who judged male household members to be at least twice as knowledgeable as women about these subjects. One hypothesis for this is that these subjects may carry a connotation of expertise due to their affiliation with actual professionals (i.e. veterinarians). By contrast, the perceived knowledge gap was a lot lower for other categories, such as nutrition and hygiene.

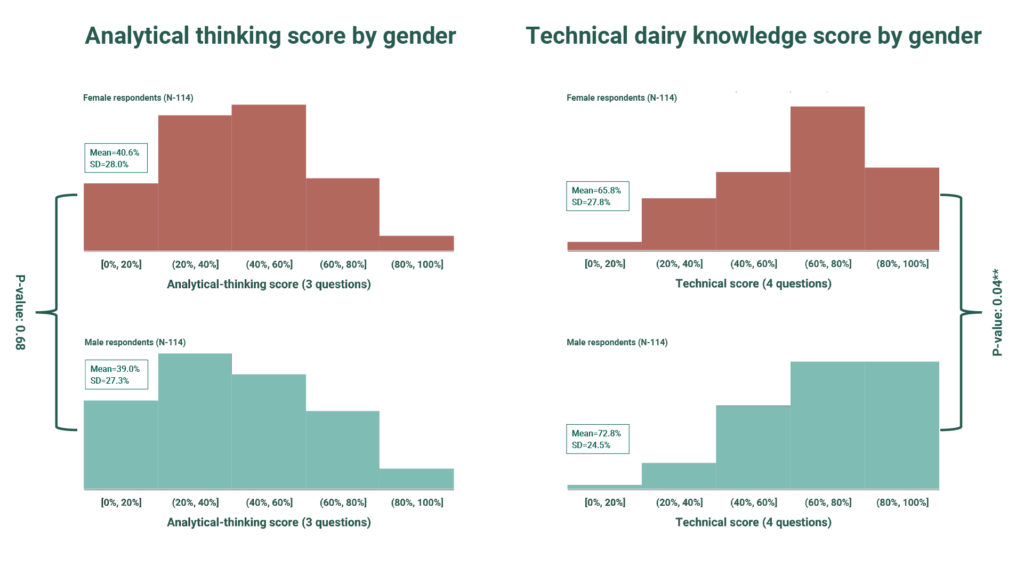

In fact, when tested, male respondents did perform significantly better than female respondents in terms of technical knowledge, with a mean score seven percentage points higher. That said, male respondents performed no better than female respondents on a test that used scenario-based questions to measure analytical thinking.

That said, two caveats must be considered in drawing conclusions from these results (shown in Figure 9): First, these results measure respondent knowledge rather than directly evaluating the knowledge of all household members. Second, the tests were brief and covered a broad array of subjects, making it impossible to evaluate whether the respondent may have deep knowledge on a particular topic. Both of these gaps suggest promising areas for future research in order to better understand the degree to which perceptions of knowledge match reality, rather than merely reflecting cultural biases; in reality, the answer may well be both, though additional empirical analysis is needed to make this claim.

Financial Agency, Intra-Household Decision-Making, and Trust

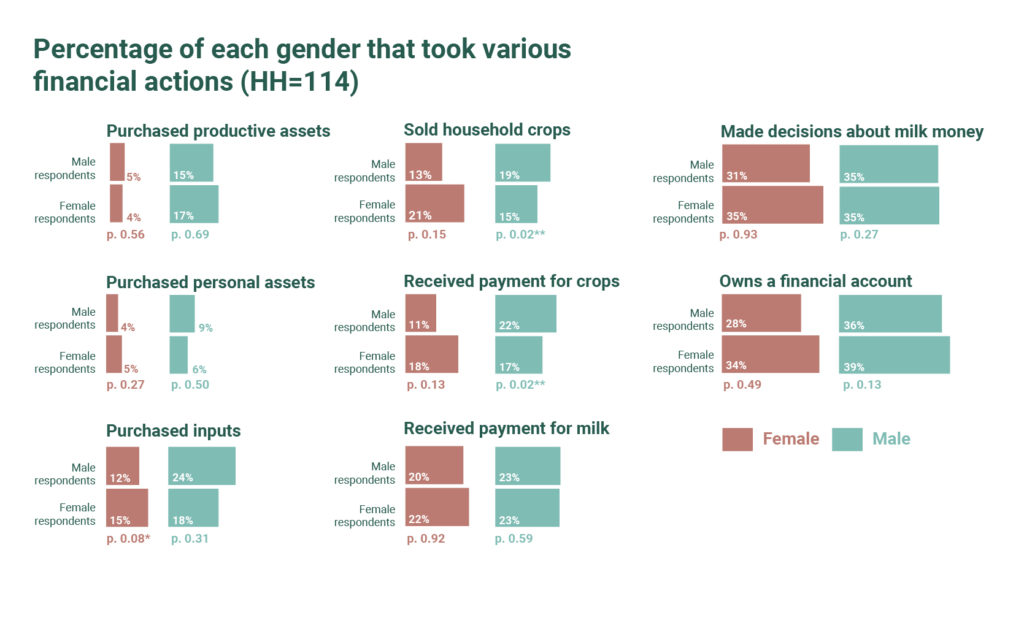

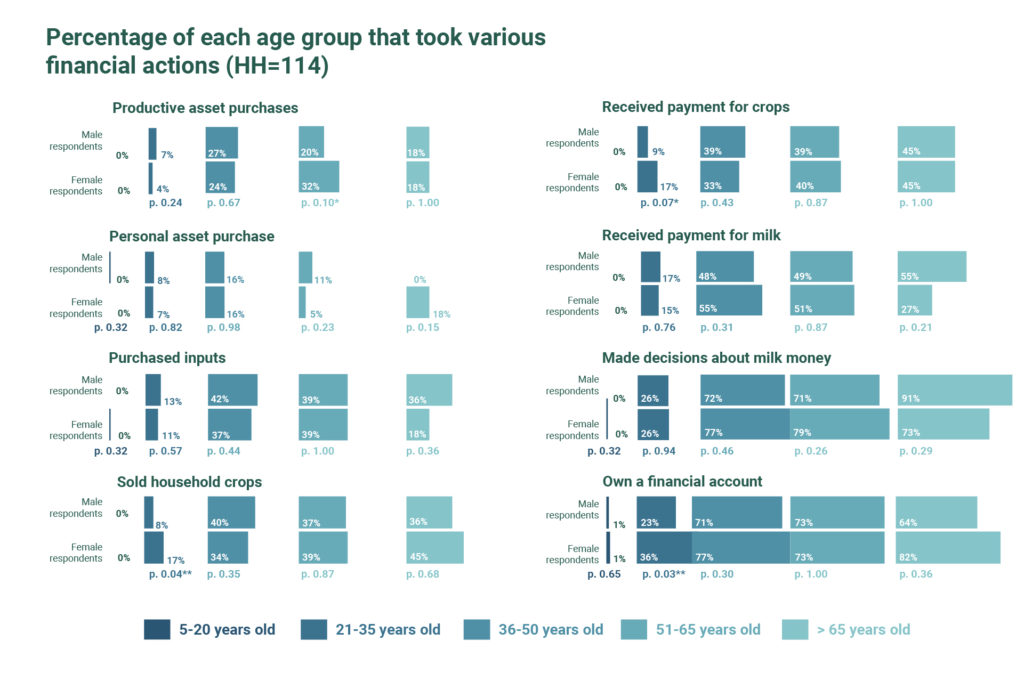

Respondents were asked a series of questions regarding their perceptions about who controlled money within the household: who in the household purchased productive assets, purchased personal assets, purchased inputs, sold household crops, received payments for crops, received payments for milk money, made decisions about spending milk money, and owned a financial account. Figures 10 and 11, respectively, analyze these results by gender and age of the household members.

Very few household members were reported to have purchased personal assets; more – overwhelmingly men – purchased productive assets, according to both male and female respondents. Male and female respondents also agreed that payment for milk money and decisions about milk money were generally split evenly within the household. Both male and female respondents also reported that household members of both genders owned financial accounts (though men did so to a slightly higher degree).

There was less agreement by respondent gender about crop farming. Male respondents reported that male household members played a larger role in selling crops, whereas female respondents reported the opposite. This same pattern was true regarding respondent perceptions of who received payment for crops. In both cases, the difference in the perception of different genders was statistically significant at the 5% level. Additionally, while respondents of both genders agreed that more male household members purchase inputs than female household members, male respondents reported the ratio to be 2:1, while female respondents reported this difference to be marginal; this disagreement was weakly statistically significant (at the 10% level). Within households, there was also comparatively more disagreement on the measures related to crop farming and associated income, as shown in Figure 12.

There are several potential explanations for the disagreement on this measure. One potential reason is there may be an internal lack of clarity within the household about who performed which category of tasks. This does not necessarily mean that individual tasks do not have a “clear” owner; alternatively, the divisions we at PxD made for the purposes of this survey may not correspond to household constructs around the division of finances. This suggests a possible area for future research: an open-ended survey consisting of structured interviews on this topic may yield interesting insights regarding financial accountability and power within the household.

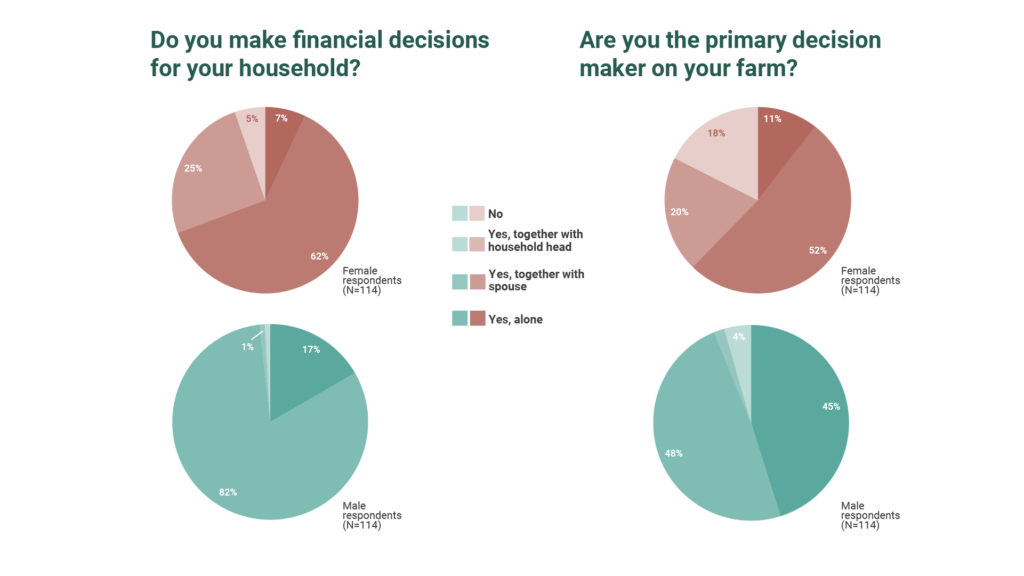

Moreover, the disagreement may reflect the fact that some tasks may be performed jointly (or in an alternating fashion) with other household members; this possibility need not be mutually exclusive with alternative divisions of labor within the household. The results in Figure 13 suggest this possibility. When asked who makes financial decisions about the farm, the majority of women (62%) and men (82%) said they made this decision together with their spouse; an additional 25% of women said they did so jointly with the household head. Even who the “primary” decision-maker was could be muddled, with 72% of women and 50% of men claiming to occupy this role jointly with either a spouse or household head.

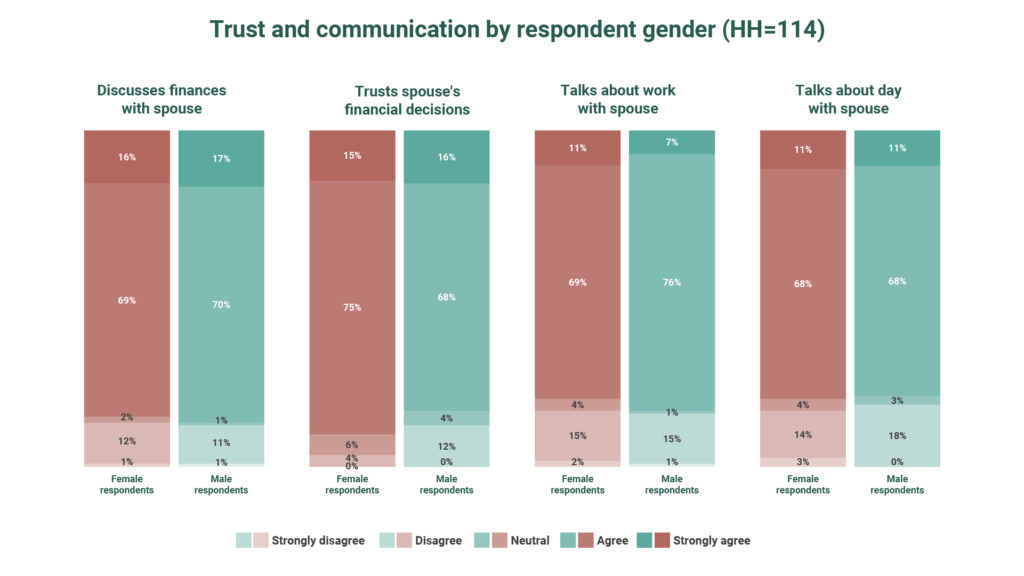

These results are ambiguous regarding whether each decision is made jointly or whether men and women have different spheres of influence within the household (and financial discretion within those spheres). However, the Likert scale questions, in which respondents were asked to agree or disagree with a number of statements about intra-household decision-making suggest that many decisions are made jointly – or at least with a substantial discussion between household members. (Figure 14)

Eighty-five percent of female respondents and 87% of male respondents reported that they discussed finances with their spouse; moreover, 90% of female respondents and 84% of male respondents reported that they trusted their spouse’s financial decisions.

In order to empirically test these subjective responses, we also asked respondents to participate in a “public goods game,” in which they could choose to augment a portion of the financial incentive they earned for completing the survey (100 Ksh, or about 1USD) to a common account. Contributing a greater amount theoretically indicates a greater degree of cooperation with one’s spouse since the amount in the common account was split evenly between spouses after both completed the exercise, regardless of how much each spouse contributed individually. The results of this game suggest a moderate amount of trust, with contributions for both women and men clustering around the midpoint of the range between zero and the total possible contribution. Figure 15 displays the distribution of these respondents’ contributions. While male respondents contributed more on average (statistically significant at the 5% level), the plurality of respondents of both gender contributed a medium amount (i.e., 40-80 Ksh)

One way to empirically evaluate whether the public goods game in practice aligns with subjective cooperation in the household is to directly compare these results. First, we regressed the correlation coefficient between the spouse’s individual Likert responses – that is, the degree to which husband and wife agreed about their level of trust or communication – on the various contribution categories (limited the covariates to the bottom quadrant of Figure 16, to make sure each category reflects a sufficient sample of people to draw meaningful conclusions). The results of this regression are shown in Table 2. There was not a high correlation between these metrics, with none of the contribution categories predicting agreement between the spouses regarding the degree of cooperation.

The next stage of analysis was to compare directly the responses to the Likert scale questions on intra-household communication and trust to the public goods game contributions. To do so, we first split the sample by respondent gender and then ran ordered logit regressions separately for each sample (Table 3). In these regressions, a positive coefficient signifies that a member of a household in that specific contribution category is more likely to “strongly agree” with the statement. To make this concrete, the variable “female mid, male high” in the female sample is equal to one for a member of that population who contributed a medium amount (40-80 Ksh) and whose husband contributed a high amount (80-100 Ksh), and is equal to zero otherwise. A positive coefficient on this variable means that a respondent in this category is more likely to “strongly agree” with an affirmative statement on the Likert response; e.g. for the first regression in the table, she is more likely to say she often discusses finances with her spouse. While all the coefficients for the regressions on the male sample and about half of the coefficient for the regressions on the female sample are positive, none of the results in either sample are statistically significant.

Since the public goods game contributions do not align with subjective measures of intrahousehold cooperation, it is unclear whether respondents are less trusting in practice than they aspirationally report to be on the subjective questions, or whether the public goods game does not accurately measure intrahousehold trust. The answer may be a combination of the two or may vary by Likert category. This suggests an area for future research.

Next Steps

This information is valuable for informing the design and operation of a dairy service that empowers rather than further marginalizes female farmers. It bears mentioning that we will continue to monitor engagement by gender to validate the insights of this survey on an ongoing basis and to make sure that we continue to reach women farmers.

That said, there are a few points we can take away from this dataset –

and we can use it to identify areas for additional research:

- In general, women and men reported that they split labor related to crop farming and grazing, and both females and males reported going to school and pursuing leisure activities. Unsurprisingly, women reported spending more time fetching water and engaging in childcare relative to men, and men were more likely to have a job outside the home. Perhaps more surprisingly, most dairy tasks were split relatively evenly by gender. Further research could investigate the ways different production systems influence household division of labor: for example, since women generally take charge of more domestic tasks, in zero-grazing households is dairy-related labor more commonly performed by women?

- Both men and women perceived men to be more knowledgeable on all topics asked about (nutrition, hygiene, artificial insemination, and feed). One positive of digital advisory compared to traditional in-person systems is that both women and men are able to read the advice on their own, and thus may be less subjected to the influence (and doubts) of peers and other household members. However, this knowledge gap may have implications for marketing: if women are systematically viewed as less knowledgeable, men may find a service that aims to disrupt that balance in the household to be threatening. Additionally, the perceived knowledge gap may pose a barrier to adoption of recommendations by women if proposed without male buy-in and perceived to not know what they are talking about.

- The allocation of financial power in the household was far from clear-cut. A similar proportion of both genders received payment for and made decisions regarding milk money, and respondents of each gender disagreed as a group about which gender sold and received payment for crops. Additionally, the majority of respondents of both genders reported making financial decisions and being a “primary decision-maker” – either individually or jointly with a spouse or household head. Finally, both male and female respondents reported discussing finances with their spouse and trusting their spouse’s financial decisions. While this has positive implications for adoption of advice by both genders, it also suggests that many decisions are made jointly and buy-in from both spouses is necessary for implementation.

- The responses of respondents of both genders to the Likert scale questions suggest a high level of intra-household communication, trust, and cooperation, at least in the subjective opinions of respondents. Similarly, the vast majority of respondents of both genders contributed at least a medium amount (40 out of a possible 100 Ksh) to the common account in the public goods game. This has positive implications for adopting recommendations, which in many cases will require collective household buy-in. That said, there remains opportunity for a more granular understanding of intra-household cooperation. For example, how does it differ in households with more defined household and/or farming roles, or in households where one spouse is clearly knowledgeable? (While this dataset contains questions to this effect, the sample size is too small to draw meaningful conclusions about precise subsets of respondents.) Outside of this data, what impact do production systems (i.e. zero-grazing) and use of particular technologies (e.g. machinery such as chaff cutters or other equipment, such as durable water tanks) have on the level of intra-household cooperation?

While the effort to better understand our service users is ongoing and our efforts to improve content and delivery are constantly evolving, this data collection yielded meaningful insights and constituted a significant step towards inclusive product and service design that can be put to use in PxD’s Kenyan dairy service – and more broadly in programming across the region.

Research Associate Sam Strimling argues that one must understand the specific needs of women to inform effective service delivery and presents an upcoming effort to gather these insights prior to launching a PAD advisory service aimed at Kenyan dairy farmers this summer. This post is the first of a two-part series, in which the subsequent installment will provide an analysis of the results for the survey described in this post. This is also the third in a series of blog posts on gender and digital development to mark International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month.

PAD empowers smallholder farmers across the developing world with actionable information to improve their wellbeing. However, there is evidence that digital advisory services like ours are underused by women. This summer we are expanding our agricultural advisory service in Kenya to the dairy sector, an arena in which women play a central role. As we prepare to launch, we are looking beyond one-size-fits-all solutions to more effectively address the unique needs, preferences, responsibilities, and constraints of female farmers.

This post is the first of two about a survey we are conducting in April 2021 to better understand gender roles and power dynamics in Kenyan dairy production and to better target our new service to the underserved needs of women in this sector. Here we describe the motivation and design of this survey. In a follow-up post, we will share insights from the results.

Invisible Women Farmers

In her spectacular book Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez details case after case in which service providers failed to deliver because they neglected to collect data about female users’ specific needs, preferences, and priorities.

The book cites the example of an organization seeking to provide “improved” seeds for staple crops: Male farmers cared more about increasing outputs. Women farmers, on the other hand, were more concerned with their input of time and labor in the field and in cooking the staple for household consumption. Since, adopting this new technology would require those doing the planting — women — to increase their time and effort, the seeds were not adopted.

Women often have less agency in agricultural and household financial decision-making. This is illustrated by Criado Perez who cites two failed attempts to introduce clean cookstoves capable of significantly reducing women’s exposure to toxic smoke. A model promoted in India required regular maintenance, which was considered men’s work. Since the new stoves improved women’s health, but didn’t directly affect men, stoves often fell into disrepair for want of maintenance. In Bangladesh, the fact that the clean cookstoves did not directly improve men’s outcomes, meant that they were not purchased at all, as men controlled household finances.

Understanding Context and Culture

Dairy is a sector of agricultural production in which tradition and gendered labor run deep. As we prepare to roll out our new advisory service, we commenced by focusing on a series of questions we need to answer to understand labor and decision-making dynamics in the sector, and within smallholder households more generally. These include:

- Who performs which tasks in the household, and within dairy farming specifically?

- Who holds the authority to make decisions?

- How systematically do users think about farming and what level of knowledge do they have about dairy farming? Does this differ by gender?

- Who controls household finances and for what types of purchases, and which accounts do they use?

- To what degree do women and men communicate about decisions and trust each other to make decisions in the interests of the household, even if one is the final arbiter of a particular decision?

The phone survey we designed to collect this information is due to be deployed in the field in early July, and will be asked to pairs of spouses. The goal is to obtain information to enable us to better target our services to both genders. By asking both men and women within the same household the same set of questions, we will be able to learn about typical responses for each gender, and we will also be able to note whether there are some questions for which we receive vastly different responses from a husband and wife within the same household.

Our survey will consist of six sections:

- Household Tasks and Time Use: This section will collect information about the gender(s) and age(s) of those performing various household tasks, including crop farming, livestock grazing, and water fetching. This section also attempts to account for household members’ time spent on other tasks, such as jobs outside the home and schoolwork. Information arising from this section will allow us to measure, for each time-use category, whether an activity is primarily performed by men, women, girls, or boys, or a combination thereof.

- Dairy Tasks: This section is similar to the Household Tasks and Time Use section, but focuses specifically on dairy farming, since the research team is most interested in using the results of this gender survey for informing the design and distribution of dairy advisory messages. This section will allow us to measure whether the following dairy tasks are primarily performed by men, women, girls, or boys: cleaning milking equipment, observing animals, giving cows water, feeding cows/calves, milking, milk transportation/sale, cleaning the housing unit (if zero-grazing or semi zero-grazing), sourcing/threshing fodder, spraying/dipping (for tick prevention), deworming, seeking veterinary treatment / artificial insemination (AI) services, identification (ear tagging), debudding/dehorning, hoof trimming, and grooming.

- Scenario-Based Questions: These are questions for which answers seek to understand respondents’ critical thinking abilities. An example of such a question would be: “Mrs Choge realized that to boost milk production beyond 7 litres a day, she needed to give her cow sufficient concentrates. For every 1.5 litres of milk above 7 litres, she gave 1 kg concentrate. How much concentrate should she give a cow producing 10 litres of milk per day?” We will disaggregate the results by gender to determine whether, on average, men or women think more systematically about dairy farming. This type of question tests the respondent’s causal reasoning, logical deduction, and systematic planning.

- Knowledge-Based Questions: This section is similar to the scenario-based section, but instead tests respondents on their technical dairy knowledge. As in that section, these questions have correct answers, and we will disaggregate the results by gender to determine whether, on average, men or women have more technical knowledge about dairy farming.

- Financial Decisions: This section will allow us to draw conclusions about who within the household holds financial power, with regards to purchases of productive assets, personal assets, and consumption goods. We will measure this empirically by collecting information, disaggregated by gender, on transaction amount as well as account type (digital/cash, joint/solo).

- Public Goods Game: In this section, respondents will be asked whether they want to augment the amount earned for participating in the survey by allocating a portion to a common account with their partner. A random amount will also be added to the survey by the research team, such that it is not possible for the respondent to lose money by completing this exercise, only to increase their earnings by a variable amount depending on the contribution made by both members of the spousal pair.1 This section allows us to collect data on trust within each spousal pair, which we assume to be correlated with the total amount contributed into the common account.

We plan to publish our findings to inform our own platform development and to make them available to other service providers and policy makers concerned with smart service design. In doing so, we plan to add to the existing body of research on gender and international development — a more complete review of which was published by my colleague Theresa Solenski in an earlier blog post.

Surveying the Evidence

Specifically, our research will add to the empirical evidence base on asymmetric information within the household. One study in Ghana found that on average, both men and women commonly underestimate or overestimate their spouse’s expenditures by more than 75%. Concerningly, this research found implications for profitability: the more imperfect the husband’s information about his wife’s expenditure, the lower the wife’s output/profit, and vice versa (Chen & Collins, 2014).

Another study from Uttar Pradesh provided an example in which women were less likely to adopt productivity-enhancing technology (in this case, laser land-leveling because they were less aware of its impact (Magnan et al. 2015)). Similarly, a study from Uganda in which agricultural videos were shown either jointly to a spousal pair, or separately to one member, found that information was not shared within the household when just one member was engaged (Lecoutere et al. 2019). These examples are particularly relevant to our work at PAD, as they highlight a way in which our service has the potential to fail: if our messages primarily reach men but women are charged with implementing the recommendations we provide (or vice versa), the suggested practices may not be adopted because we failed to get the information into the hands of women who can make it actionable.

Our survey will contribute to the literature on within-household asymmetric information in two ways. First, the sections on household tasks / time-use, dairy tasks, and finances will — in addition to providing information about gender roles — enable us to compare directly the wife’s knowledge of household affairs to that of her husband (and vice versa). Second, the sections quizzing respondents on dairy knowledge and testing of systematic thinking through scenario-based questions will measure within-household information asymmetries with respect to dairy farming.

Imperfect communication and limited trust also have implications for message adoption: Qualitative evidence from a focus group discussion with 113 male farmers and 141 female farmers in Malawi suggests that men often do not trust agricultural information received from their wives, and female farmers may be hesitant to suggest new agricultural practices for fear of retribution (Ragasa et. al., 2019). Another group of researchers partnered with Kakira Sugar Ltd., a large sugar company in Uganda that sources sugarcane through contracts with smallholder farmers, the vast majority of whom are men. This study implemented an intervention in which men were encouraged to transfer uncontracted blocks of sugarcane to their wives. Since both spouses needed to agree to the proposed intervention, whether the men were willing to do so provided in and of itself a measurement of trust. The researchers found a man was less willing to transfer the contract — i.e. was less trusting of his wife’s capabilities in this respect — if the household had fewer assets and/or expenditures, if his wife was not already involved in sugarcane farming, or if he had previously expressed a preference for managing the household’s finances himself (Ambler et al., 2021).

In our survey, we plan to collect novel data on trust within the household using the public goods game. Ambler et. al. applied a similar approach in their baseline survey, and collected time use data. They found that cooperation in the public goods game significantly predicted a husband’s willingness to transfer the contract to his wife, but time-use data collected did not have the same predictive power.

Finally, by collecting information on respondent demographics and knowledge alongside information about financial decision-making and intra-household communication and trust, our survey will add to existing literature about factors that influence bargaining power within the household. For example, a descriptive analysis of a Tanzania spousal dataset shows that a woman’s age, health, labor hours, and education were positively correlated with her authority to make decisions in the household; however, the number of children she had and her husband’s community standing were negatively correlated with this authority (Anderson et. al., 2017). In our survey, we plan to collect information on each respondent’s age, education level, and number of children, which we can use to disaggregate responses about financial decision-making and the amount contributed to the collective account in the public goods game. This will allow us to investigate whether factors similar to those observed in Tanzania hold weight in the Kenyan context.

Next Steps

We plan to begin the survey in early April and will interview approximately 600 dairy farmers via phone, over two rounds.2 We will first survey 300 respondents from dairy cooperatives, during which we will ask about contact information for their spouses. We will then complete a second round with the spouses of the first round participants.

The sample for the gender survey was constructed to select a representative sample for the two cooperatives interested in partnering with us for this survey, Sirikwa Dairies and General Limited and Katheri Dairy Farmers Cooperative Society. We chose these two cooperatives because they represent the two primary dairy producing regions in Kenya, and because they were able and willing to provide demographic information for their membership sufficient for us to stratify the sample by gender, total production, and total deductions on member accounts for expenses such as agrovet purchases, artificial insemination, veterinary services, and cash advances. This information will enable us to research intra-household gender dynamics for farmers of different levels of farming sophistication.

We expect this research will yield important insights, and we plan to publish the results in a subsequent blog post. The most important outcome, however, will be to improve our content and message delivery for the dairy farmers we serve.

_______________________________________