Given existing poverty, dependence on agriculture for livelihoods, and lack of access to safety nets, poor smallholder families in low- and middle-income countries are particularly vulnerable to exogenous shocks. In March 2020, when the world shut down and told people to stay home to mitigate the public health impacts of COVID-19, many poor smallholder families were left reeling. In response to the growing humanitarian crisis, in April 2020 the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) launched a multi-donor COVID-19 Rural Poor Stimulus Facility (RPSF) to improve food security and resilience among poor rural people during the pandemic.

PxD was one of several RPSF grant recipients and interventions selected, all of which focused on either digital services, providing inputs or assets, access to markets, or targeting funds for rural financial services. In collaboration with the IFAD country teams and their government partners, PxD implemented three digital advisory services in Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan between August 2020 and September 2021 to provide digital extension services to approximately two million users. PxD reached 1.2 million farmers in Pakistan, 650,000 in Kenya, and 100,000 in Nigeria, surpassing the initiative’s target of 1.7 million farmers. This includes roughly 178,000 IFAD project beneficiaries across the three countries. These farmers received timely, relevant, and customized agricultural recommendations to improve their farm productivity directly via their mobile phones.

After successfully launching the initial digital services and delivering agricultural advice, IFAD and PxD conducted RPSF rapid assessments in late 2021 to assess farmer outcomes in all three countries. The surveys were designed to compare production, sales, income, food security, and resilience outcomes after the onset of COVID-19 but before the digital advisory intervention (the pre-intervention period) and after the intervention (the post-intervention period). We define resilience as the ability to cope with unexpected challenges and shocks, such as the ability to deal with drought/floods, pest invasions, and rising input prices. The final sample sizes for Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan were 400, 395, and 600, respectively. We stratified the samples by gender, youth status.Youth was defined as heads of households under 35, agro-ecological zone (AEZ) or state1Agro-ecological zones were used in Kenya and Pakistan; the survey covered seven (including unknown) and five AEZs, respectively. We stratified by seven states in Nigeria., and engagement level Kenya and Nigeria only, where we differentiate between high and low engaged users using the median number of messages or calls responded to. so we could analyze and compare outcomes by these subgroups. Within a country, we tested for statistical significance of crop, livestock, poultry, and agribusiness production and sales, as well as food security and income indicators between the pre-intervention and post-intervention period. The samples of farmers selected for the intervention and the surveys were randomly selected from our user bases of IFAD beneficiaries within each country, which may not be nationally representative. Moreover, this is a descriptive analysis, and we cannot infer whether PxD’s services had a causal impact on outcomes reported after the intervention because of the lack of an experimental design (there was no control group).

Farmer-reported outcomes during COVID-19, pre-intervention

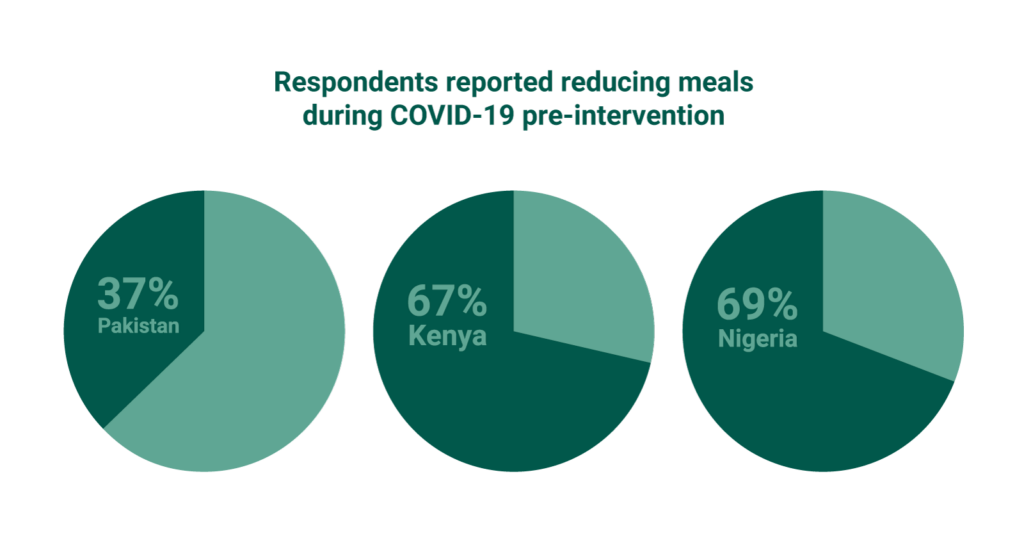

Across all three countries, most respondents reported a loss or reduction in production, sales, number of meals, and resiliency during COVID-19 prior to PxD’s RPSF intervention (pre-intervention period). Respondents from Pakistan seemed to be the least affected by the onset of COVID-19, as fewer respondents reported reductions or losses, compared to Nigeria or Kenya. Moreover, almost half as many respondents reported reducing meals (37%) than in Kenya (67%) or Nigeria (69%). For all indicators except food security, respondents from Kenya reported the worst outcomes, including over 98% who reported lost or reduced production during COVID-19. There was also a wide disparity between the percentage of respondents reporting selling assets across the three countries. Almost two-thirds (65%) of respondents in Kenya reported selling assets because of COVID-19, whereas less than 10% of respondents in Nigeria reported the same.

We also disaggregated production and sales outcomes by specific types of farming that farmers engage in, namely: crop growing, livestock rearing, poultry raising, and agribusiness activities. We find that agribusiness production and sales suffered the most in Pakistan when compared to crop, livestock, and poultry. This finding could be attributed to COVID-19 restrictions which limited the ability to engage in business activities. However, in Kenya and Nigeria, farmers reported larger reductions in crop production and sales compared to livestock, poultry, or agribusiness.

While respondents in Kenya overall seemed to fare the worst in the pre-intervention period, Kenyan women suffered disproportionately more. For example, all Kenyan women reported a reduction or loss of production during the pandemic, and women reported higher reductions than men for all other indicators. We don’t see the same clear pattern in Nigeria or Pakistan, although more women from all three countries reported worse food security outcomes than men. This could in part be due to cultural expectations of women eating last and in small portions, compared to men in the same household.

… and post-intervention

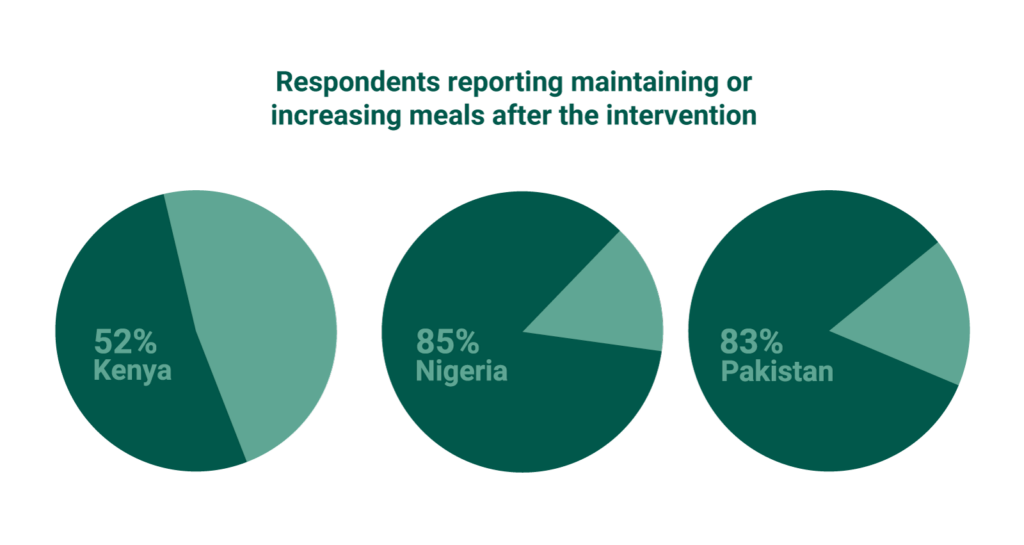

After the RPSF intervention concluded in late 2021, during a lull in the COVID-19 pandemic between the Delta and Omicron waves, we observed encouraging evidence of improved farmer resilience. Respondents in all three countries indicated that conditions had improved relative to the early phase of the pandemic, at the onset of COVID-19 but before the digital advisory intervention (the pre-intervention period), however, some fared better than others. For example, Nigerian respondents reported maintaining or improving production, sales, income, meals eaten, resilience, and asset indicators at higher rates than those in Kenya and Pakistan. Considering the poor conditions they reported during COVID-19, we take this as a sign that Nigerian respondents may have recovered from the pandemic more quickly than their counterparts in Kenya and Pakistan. Conversely, in addition to suffering the worst outcomes in the pre-intervention period, Kenyan respondents indicated that they maintained or improved outcomes the least in the post-intervention period. Only about half of Kenyan respondents reported production and meals were maintained or increased, and less than half reported maintaining or increasing sales, income, resiliency, and assets. Only 25.5% of Kenyan respondents reported income stayed the same or improved, highlighting that Kenyan farmers have struggled significantly in recovering from the pandemic, even after receiving the intervention.

Kenya experienced severe drought during the long rains 2021 season (February-March to June-August depending on location) while the RPSF intervention was underway and during the collection of this data, which likely contributed to the poor outcomes reported after the RPSF intervention. For example, many farmers reported failed crops rendering it impossible to follow the customized digital advisory of the intervention, and to harvest and sell their crop. This is corroborated by reports estimating reduced crop production of up to 70% in Kenya during the drought2Oxfam International, 2022 https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/many-28-million-people-across-east-africa-risk-extreme-hunger-if-rains-fail-again.

Disaggregating the results by type of farming activity, we find that Kenyan and Pakistani farmers reported production and sales reductions in agribusiness the most, even after the RPSF intervention. Because COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the government persisted during the intervention and survey period, we suspect that these restrictions played a role in farmers’ ability to engage in agribusiness, resulting in lower production and sales than other farm activities. In Nigeria in the post-intervention period, farmers reported reductions in production and sales for crop farming more than the other surveyed farm activities, suggesting that even though there were improvements to production and sales after the intervention, farmers’ crop yields suffered the most, relative to their livestock, poultry, and agribusiness activities.

In Pakistan, we observe better outcomes than in Kenya, although slightly less than half (48%) of respondents indicated they maintained or improved their income after RPSF, and only slightly more than half (57%) reported maintaining or improving their sales. Greater than expected wheat yields might have contributed to the better outcomes observed in Pakistan. But while these figures are somewhat encouraging and indicate that some Pakistani farmers were able to recover from COVID-19-related shocks, it also indicates that a significant share of farmers has not recovered. This could be because of the lingering effects of COVID-19 such as global trade shocks and new variants disrupting economic activity via additional lockdowns.

Similar to the outcomes reported during COVID-19, Kenyan women respondents indicated they maintained or improved outcomes less than their male counterparts after the intervention, across all indicators except assets. Only 17.3% of women reported maintaining or improving their income after RPSF, which is almost half the proportion for men, highlighting the predicament of women in Kenya in the face of COVID-19 and drought-related shocks. In Pakistan, while overall outcomes were better, we still note women reported maintaining or improving production, sales, income, and meals at lower rates than men. In Nigeria, a higher proportion of women actually reported maintaining or improving income, meals, and resiliency, and for the other indicators, women reported maintaining and improving at similar rates to Nigerian men. However, we also found evidence that women were disproportionately affected in the livestock sector; Nigerian women were more likely to report reductions in livestock production and sales after RPSF, compared to their male counterparts. Across all three countries, women reported faring worse than men in maintaining or increasing sales.

We also disaggregated the post-intervention RPSF results by farmers’ level of engagement with the PxD service, where we defined highly engaged users as having picked up or responded to more than the median number of calls (Nigeria) or SMS messages (Kenya)3We did not disaggregate by level of engagement in Pakistan.. In Kenya, we did not see any clear patterns by engagement level. However, in Nigeria, we found that highly engaged users (who picked up more than seven calls) reported maintaining or improving production, sales, and income at a higher rate than lower engaged users. This result provides suggestive evidence to our theory of change that users who more actively engage with our services may implement more of (or implement better) our recommendations, leading to improved outcomes.

It was challenging to draw clear conclusions from the data at the level of agro-ecological zone and state, due to the small number of respondents per zone or state. For example, in Kenya, there is some evidence that households from the upper highlands (UH) AEZ fared better than respondents in other zones. This may be because the UH zone was less affected by severe drought than other more arid regions in the country. In Nigeria, respondents in Katsina fared worse than the other states, reporting the highest level of reductions in most production, sales, food security, and resiliency measures. We suspect that local terrorism and banditry in the state played a role in the poor outcomes reported there. Meanwhile, respondents in the Nigerian state of Jigawa reported faring the best, which may be because widespread telecommunication shutdowns that plagued the country during the grant period were avoided, and the state is relatively peaceful compared to others in the north.

While the initial COVID-19 shock occurred in early 2020, the results of the surveys suggest that there are strong lingering negative effects in all three countries (as well as other severe shocks such as extreme weather events and terrorism) and more direct support is needed to return smallholder farmers to their pre-COVID-19 state. While this analysis does not estimate the causal impact of PxD services, we plan to use the data from this analysis to improve our services to more effectively meet farmers’ needs. In Kenya, we hope to specifically address weather-related shocks such as severe drought. Weather-related services are already being explored in Pakistan and India and learnings from these pilots might also be applicable in Kenya. Based on the evidence that women found it more difficult to cope and recover from COVID-19, we hope to develop women-targeted interventions designed to reach more women users or develop content tailored to women’s needs. This will build on gender-focused service experimentation we have undertaken such as providing messages with a female narrator and nudges encouraging spouses to share PxD advisory with each other, as well as implementation of advisories focused on female-dominated value chains such as kitchen gardens, dairy, and livestock.

Since the conclusion of the intervention and endline survey, farmers’ situations have become even direr. Experts warn of rising food shortages and hunger due to high global inflation and supply chain disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine. The World Bank estimates that the Agricultural Price Index is 14% higher as of this June compared to January and 94% of low-income countries are experiencing food price inflation greater than 5%. The already looming food crisis is expected to be exacerbated by a sharp increase in fertilizer prices, largely driven by the war in Ukraine, as Russia and its ally Belarus produce 40% of the world’s supply of potash, and Russia and Ukraine together export 28% of nitrogen and phosphorus-based fertilizers. Within this context and amid the backdrop of the ongoing pandemic, the need for strong support for poor smallholder families is urgent.

Uzoamaka Ugochukwu, PxD’s Nigeria Country Launch Manager, was selected to present a “tech demonstration” at the 2022 rendition of the Global Digital Development Forum. The demonstration presents how PxD leveraged our in-house tech platform, Paddy, and our experience implementing digital advisory services to rapidly build, deploy and scale services to 107,000 smallholder farmers in Nigeria.

PxD’s forthcoming 2021 Annual Report will be conveyed primarily via video using a similar design to that deployed in this video. Watch this space!

Precision Development (PxD) leverages needs assessment research to inform our agricultural extension services, and we survey our farmers to gauge their opinion of our services. Sourcing information from farmers gives us direct insight into the challenges and opportunities farmers face. We use these insights to improve the design of our services and the content of our advisory messages in an effort to align them most closely to farmers’ informational needs.

Through the course of 2021, as we designed and rolled out a new advisory service for farmers in Nigeria, we conducted five surveys to inform more evidence-based decision-making:

- Baseline survey (Jan 21)

- Dry season feedback survey (7th April)

- Wet season feedback survey (3rd August)

- Wet mid-season adoption and knowledge survey (20th August)

- End-line survey (December – analysis is ongoing)

Having a clear line of sight into the needs of farmers has been critical as the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved and created new and shifting challenges for farmers in remote areas.

At PxD we believe the information revolution and the spread of mobile technology to people living in poverty offer unprecedented opportunities for increasing access to information at scale and at a very low cost. We promote digital information-sharing systems to distribute quality, actionable and targeted information. By obtaining regular feedback from farmers through research in behavioral economics and social learning our services are improved to encourage the adoption and assimilation of practical information and improved or adapted production practices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gathering Insights on Farmers’ Needs

Utilizing an emergency grant from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), PxD began working in Nigeria in November 2020 – eight months after the World Health Organization’s assessment of COVID-19 as a “pandemic”. PxD’s initial service, delivered during the dry season, reached more than 5,000 smallholder farmers within three months of the program’s launch. The service was then scaled to serve more than 100,000 users during Nigeria’s primary growing season, the wet season. PxD collaborated with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) to implement the Nigeria Rural Poor Stimulus Facility (RPSF), funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). IFAD’s funding objective was to assist Nigeria to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on smallholder farmers and its goal was to insulate domestic food supply by supporting access to affordable inputs and advisory to sustain production.

We believe that gathering baseline information from farmers about their needs was a critical factor that contributed to the success of PxD’s digital advisory service in Nigeria. We conducted a baseline survey in January 2021 to collect information on:

- Farmers’ socio-economic, demographic, and institutional characteristics;

- Their knowledge about dry season cultivation of crops and Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs); and

- Their perception of and willingness to receive mobile advisory services.

The survey interviewed 254 farmers randomly selected from a database of over 5,000 farmers. Findings from the baseline survey showed that 95% of the respondents indicated they would be interested in planting during the dry season. The remaining five percent identified lack of water and access to land as major barriers to engaging in any planting in the dry season. The survey also revealed that a lack of appropriate inputs, pests and disease problems, personal preferences, bad harvests, distance from water, and knowledge gaps are important challenges for the smallholder farmers.

Listening to the Farmers from the ‘Get-go’!

At PxD, we prioritize offering our users valuable and practical information to change or improve farmer behaviors and farm productivity. We do this by providing information customized – wherever possible – to a farmer’s location, market conditions, and personal characteristics. To calibrate our systems effectively, it is essential that we hear from the farmers themselves to understand their needs as they relate to their socio-economic realities. The results of our dry season baseline survey provided useful insights about farmers’ crop choices as well as their previous or existing crop practices. This information was vital for informing our product development and service delivery.

Only 56% of farmers surveyed during our baseline assessment had ever attended any training or workshops on crop production techniques. The survey also revealed that rice was the preferred crop for the dry season, followed by onions, tomatoes, and other vegetable crops. These and other findings helped us develop recommendations for specific topics, crop value chains, and farmer groups.

While just over half of farmers surveyed at baseline had experienced some kind of extension outreach, the advisory content received varied. For example, fewer than 50% of farmers had received training on GAPs such as:

- Weed management;

- Harvest and postharvest handling;

- Water management;

- Nursery establishment;

- Transplanting; and

- Input selection.

Whereas more than 50% had received training on:

- Pest and disease management;

- Fertilizer application; and

- Land preparation.

Importantly, the team also learned that fewer than 50% of the respondents had applied any of the GAPs or any other training they had received.

Monitoring Farmers’ Engagement and Feedback

One crucial aspect of our work at PxD is to gather evidence on the impact of our services on smallholder farmers. We are a learning organization that rigorously tests our services through experimentation and research. We have a high level of flexibility to adapt to the complexities of the various geographies where we work. Regular monitoring and evaluation of our interventions help us understand how our services are impacting our users and give us early insights into potential problems. PxD incorporates insights from behavioral economics, human-centered design, and social learning theory, and uses A/B testing and data science to identify what types of information and delivery mechanisms work best for our users.

In Nigeria, a feedback survey was conducted at the end of the 2021 dry season to assess farmers’ perceptions and use of the push call services, and to analyze factors that influenced their engagement with the service. The sample comprised 700 farmers randomly drawn from the seven states where the service was provided (Borno, Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara). The sample distribution was 500 farmers from the ‘high participation’ group (with a more than 50% average listening rate) and 200 farmers from the ‘low participation’ group (with a less than 50% average listening rate). The survey results indicated that 88% of respondents, or a member of their family, recalled listening to any of the push call messages, while 86% reported “continuing to listen” to the calls (a proxy for continued engagement). This was particularly significant as it was the first season of the PxD program in West Africa.

Furthermore, a knowledge and adoption survey conducted in August, during the wet season campaign, indicated that 85% of respondents reported adopting at least one GAP, while 95% of respondents correctly answered one or more of the five knowledge questions asked in the survey. The survey also measured service satisfaction. Analysis of the survey results revealed a positive net promoter score of 39 (on a scale of -100 to 100), indicating that a majority of respondents (53%) said that they were likely to promote the service to other users, while only 14% of the sample reported being unlikely to recommend it or continue using the service.

To achieve behavioral change, the information conveyed should be accessible and of practical use to rural farmers. Ninety-four percent of respondents to the wet season feedback survey answered ‘Yes’ when asked: Were the messages clear and loud enough so that you could understand their content? In addition, 96% confirmed that they or a household member adopted the agronomic advice during the planting season.

Research shows that access to extension services is a key driver of technology adoption. Farmers are usually informed about new technology and its effective use by extension agents (Genius et al., 2010). Furthermore, the extension agents form a link between the researchers and users of the information, which helps to reduce transaction costs incurred when passing on the information about the new technology to a large heterogeneous population of farmers (Genius et al., 2010).

However, in-person extension services are expensive and time-consuming to deliver, and very difficult to scale. One can’t copy-and-paste trained extension agents, or their means of transportation, or guarantee that when extension agents make contact with a farmer the information they carry with them will be temporally valuable or practical. As evidenced by feedback from our farmers, very few Nigerian smallholder farmers have benefitted from extension services in the past. Feedback from farmers suggests that PxD’s model of digital agricultural extension in Nigeria, implemented in collaboration with partner organizations to maximize scale and at very low costs per farmer served1 Our Nigeria service was delivered at an average annual cost of $3.45 per farmer served, which compares extremely favorably with the costs of in-person extension services. With further scaling, we expect this number would fall further, and more closely align with PxD’s average cost per user served which at the time of writing was $1.61 per user per year., was considered by farmers to be valuable and relevant. Many farmers reported implementing the advice we broadcast to them. Digital delivery channels meant that we were able to deliver extension services under pandemic conditions when human movement and personal interactions were limited or prohibited.

The success and rapid scaling of our Nigeria service were built on strong partnerships, a portable and customizable in–house technology platform, and a service delivery model that we constantly update with information sourced from the farmers we serve, the results of surveys and experimentation, and rigorous evidence on the impact of our work. We look forward to building on our Nigerian successes and further assisting farmers in need as they confront wide-ranging challenges in very difficult conditions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the RPSF financial support of IFAD. Many thanks to the Nigerian team for their collective effort in drafting this post, and Emmanuel Bakirdjian, Theresa Solenski, Moira Levy, and Jonathan Faull for their contributions.

References

Balana B.B., Oyeyemi M.A., Ogunniyi A.I., Fasoranti A., Edeh H., Aiki J., and Andam K.S. (2020). The effects of COVID-19 policies on livelihoods and food security of smallholder farm households in Nigeria: Descriptive results from a phone survey. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1979. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.134179

Mungai L.M., Snapp S., Messina J.P., Chikowo R., Smith A., Anders E., Richardson R.B., and Li G. (2016). Smallholder Farms and the Potential for Sustainable Intensification. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01720

Paul A. Francis, John T. Milimo, Chosani A. Njobvu, and Stephen P. M. Tembo (2013). Listening to Farmers. Participatory Assessment of Policy Reform in Zambia’s Agriculture Sector. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-4025-5

Genius, M., Koundouri, M., Nauges, C., and Tzouvelekas, V. (2010). Information Transmission in Irrigation Technology Adoption and Diffusion: Social Learning, Extension Services and Spatial Effects. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aat054

Crystal Aghadi, Research Associate, John Babadara, Program Associate, and Godfrey Petgrave, Agronomist, report on PxD Nigeria’s most ambitious challenge yet: delivering advisory information to over 100,000 Nigerian smallholder farmers.

Team PxD Nigeria is in the process of unleashing a wave of scientifically validated agricultural information to support the productivity of over 100,000 smallholder farmers during Nigeria’s 2021 Wet Season. Information to promote optimal cultivation and input use in support of nine priority crops is being delivered via automated push calls directly to the mobile phones of farmers across eleven Nigerian states, including Nigeria’s poorest, and conflict-affected states in the Northeast and Northwest Regions of the country. The Wet Season is particularly important for poorer farmers who rely on rainfed agriculture and is the most intensive and productive cultivation period of the year.

The messages that Team PxD Nigeria is delivering have been designed to maximize accessibility and relevance to smallholder farmers’ needs with the intention of buttressing and improving agricultural productivity and incomes at a time of heightened need. The message delivery schedule is aligned to critical decision points in the agricultural calendar so that farmers receive information when it is most practical and actionable for them. Our advisory content, and the timing of its delivery, are designed to assist users to make more informed and productive decisions during pre-planting, cultivation, and the harvest and post-harvest periods.

Our Partners

On 12 November 2020 the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and PxD announced the inception of the Nigeria Rural Poor Stimulus Facility (NRPSF).

The Nigeria RPSF is designed to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on smallholder farmers and to insulate domestic food supply by supporting access to affordable inputs and advisory to sustain production. The NRPSF is funded by, and aligned with, IFAD’s overarching Rural Poor Stimulus Facility which was established in 2020 to improve the resilience of rural livelihoods in the context of the COVID crisis by ensuring timely access to inputs, information, markets, and liquidity. The initiative is being implemented under the auspices of the Climate Change Adaptation and Agribusiness Support Programme (CASP), a comprehensive action plan being implemented by FMARD with support from IFAD.

PxD is working with IFAD and the Government of Nigeria’s CASP initiative to build and scale mobile phone-based agricultural extension to support smallholder farmers in the seven Northern Nigerian states of Borno, Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara, as well as Ebonyi (Southeast), Nasarawa and Niger (Central), and Ogun (Southwest). To reach more users and maximize the impact of the grant, PxD is collaborating with additional actors and initiatives driving innovation in the Nigerian agriculture sector, including: the IFAD-supported Value Chain Development Program (VCDP) which uses a demand-driven approach to develop markets, address constraints and increase market access for smallholder farmers and medium-scale agro-processors along Nigeria’s cassava and rice value chains. PxD is also working with AgroXchange Technology, a private technology firm with on-the-ground access to farmers, that uses a digital profiling platform to facilitate access to markets, credit and inputs on the part of Nigerian farmers. We are also working to deepen the reach and access a new group of smallholders recruited by Pacific Ring (Cassanovas), a private firm working to expand production and post-production opportunities for cassava farmers in collaboration with the Nasarawa State Ministry of Agriculture.

Operational Context

Even before COVID-19’s ill winds began to buffet the global economy, Nigeria’s economic performance confronted significant headwinds linked to lower oil and commodity prices. In the near term, the World Bank expects unemployment and underemployment to increase, with disproportionately negative implications for the poor.

The Wet Season advisory campaign will empower smallholder farmers in Borno, Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara States – across Nigeria’s Northeast and Northwest Regions – where poor human security has compounded legacy developmental challenges with negative implications for smallholder livelihoods and food security. The farmers who will receive information from PxD in the seven states that span Nigeria’s northern border are beneficiaries of IFAD’s CASP initiative. The 2021 Wet Season advisory campaign will also deliver advisory information to smallholder farmers in Ebonyi, Nasarawa, Niger, and Ogun states. Farmers in these additional four geographies are representative of other regions – the Southeast, North central and Southwest of the country, respectively. It is hoped that their inclusion will serve as further proof of concept for the integration of digital extension services in Nigeria, country-wide and at scale. The addition of farmers from Ebonyi, Nasarawa, Niger and Ogun states was made possible through a strategic collaboration with the IFAD supported Value Chain Development Program (VCDP), and collaboration with private sector partners actively implementing programs to support smallholder farmers.

A significant challenge in fragile and conflict-affected areas is balancing the need for extension services with multi-dimensional risks. Insecurity in Northern Nigeria has negatively impacted farming. When overlaid with the preexisting high levels of poverty in the region, conflict-affected and constrained supply chains, market disruptions, damaged infrastructure, and human displacement are contributing to an escalating food crisis for many communities. PxD’s digital extension services can be provided to farmers without the need for in-person contact, a significant advantage in conflict-affected areas, and with regard to ongoing physical distancing protocols necessitated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Need throughout the region is expected to be particularly pressing this year as the onset of the main rainy season has been delayed. The Nigeria Meteorological Agency (NiMET) forecast predicts a combination of delayed rains, fewer days of rain, and a longer than usual dry spell, particularly in the Northern region where our service is concentrated.

Between January and March 2021, PxD Nigeria implemented our inaugural digital extension service which broadcast Dry Season advisory to a cohort of 5,613 smallholder farmers to support the cultivation of five priority crops. In April 2021, after the completion of the Dry Season campaign, the team conducted a survey of farmers to assess the efficacy of the service and inform future programming. Prominent among the information received from farmers was that only 26 percent of farmers surveyed reported access to any other form of extension service. The dearth of alternative and accessible sources of trustworthy agricultural information underscores the utility of digital extension in remote- and conflict-affected areas, and additional challenges that confront in-person extension services in the context of a pandemic.

How the System Works

PxD’s advisory information is delivered via push calls coordinated through a Paddy-powered voice-based platform and focuses on increasing smallholder farmer knowledge about affordable inputs and promoting activities that improve productivity and income generation.

Paddy is what we call our backend technology – the framework we use for building two-way communication applications to communicate with our users on their mobile phones. Paddy’s versatility allows for a great deal of automation, provides comprehensive monitoring tools, and enables our team to run tests and tweak the platform in real-time as we concurrently deliver our advisory service.

Advisory calls are timed so that the first attempt to place a call to each farmer is at 7AM. If a farmer does not pick up the initial call, three retries will be attempted at the same time on the subsequent three days. The timing of calls is informed by PxD’s experience delivering an initial service to 5,613 farmers during the Dry Season, and a follow-up survey with users of that service. The call times explicitly avoid times when farmers may be observing religious practices.

e-Extension in Practice

A total of 85 push call messages have been developed to support the cultivation of nine priority crops during the Wet Season (10x Millet-related messages, 9x Soyabean, 9x Cowpea, 10x Cassava, 10x Sorghum, 9x Cabbage, 8x Groundnut, 10x Maize, and 10x Rice). Message content addresses key practices farmers can adopt to improve their productivity and yields.

The team has developed approximately two hours of content to be pushed via voice calls to farmers to support the cultivation of nine crops. Extrapolating from the average pickup and listening rates we observed during the Dry Season campaign, we hope that farmers will access between 600,000 and 900,000 total minutes of content depending on pickup and listening rates.

Each message is translated and recorded in Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba to accommodate users in Nigeria’s various regions. Messages are designed to be delivered in approximately two minutes or less to maximize information retention and mitigate the potential for distractions while listening. Messages prioritize information about the following Good Agronomic Practices (GAP):

- Soil requirements for selected crops

- Climatic requirements for selected crops

- Land preparation for selected crops

- Sowing/planting methods for selected crops

- Fertilizer Management

- Integrated Pest and Disease Management

- Disease management – Bacteria, Fungi, and Virus

- Key Pests and Diseases management for selected crops

- Good Harvest practices

- Good Post-harvest practices

Examples of calls to farmers.

Hausa Audio file of 1st Millet Call to Farmers (Women narrator):

English Translation: Do you know that millet does not grow well in flooded conditions? In preparation for the wet season, do not grow millet on soils prone to waterlogging and flooding. This is because doing so will cause shallow rooting, low seed protein, and poor yields. Millet can be grown on a wide variety of soils ranging from clay loams to deep sands. For better yields and grain quality, it is best to grow millet in deep, well-drained productive soil. Properly managed soil and good tillage practices will give millet deep rooting which will result in good seed production and higher yields for the farmer.

Igbo Audio file of 5th Cassava Call to Farmers (Women narrator):

English Translation: Applying fertilizer on your cassava farm should be based on results from soil analysis, but if the soil test is not done, you can then use the land history and vegetation as a guide. In the absence of any soil testing agents, you can also determine the quality of your soil by simply taking note of the weeds or other plants that are growing on the land before clearing. If you observe more broadleaf weeds on the land, this is a good sign that the soil is good. Another physical way to check for the quality of your soil is to check if it smells, a rich soil will smell like dirt while a bad soil will have no smell at all. For best yield, apply 3 – 4 bags NPK 15:15:15 on 1 acre of cassava farm. Apply Fertilizer at 8 weeks after planting. Apply 1 match box-full of NPK fertilizer around each stem, 10 cm from the plant, this is two fingers away from the stem, or broadcast with care around the plant, making sure the fertilizer does not touch the stem or leaves so that it doesn’t burn the plant.

Hausa Audio file of 5th Rice Call to Farmers (Man narrator):

English Translation: Preventing pests in your field will save money on pesticides and increase the value of your harvest. Intercropping beans with your rice can discourage pests from your field. Keeping your field clear of weeds, debris, and dead plants will also keep pests away.

Visit your field regularly and check at least 10 plants for signs of pests. If you notice signs of pests, speak to your agro dealer immediately for advice. Be careful– if chemical pesticides are used incorrectly or used too much, pest problems can become worse in the future.

Since August 2020, PAD has collaborated with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), a UN affiliated multilateral agency, to deliver digital advisory to assist smallholder farmers in Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan to boost productivity and resiliency as they navigate the evolving impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 05 May 2021, IFAD convened an #IFADinnovationtalk webinar to showcase our partnership under the auspices of presentations and a panel discussion entitled ‘Digital Agriculture and the Rural Poor: Challenges and opportunities in delivering results’. Keynote speeches were delivered by Michael Kremer, PAD co-founder and Nobel Prize winner, and Owen Barder, PAD CEO. Our colleague Uzoamaka Ugochukwu, Nigeria Country Launch Manager, participated in a panel with Vivian Hoffman (a PAD research partner at IFPRI) and Dr. Zahoor-ul-Hassan (a key champion of our work in the Government of Punjab, Pakistan), and Patrick Habamenshi (country manager of IFAD Nigeria).

As Owen Barder, PAD’s CEO, stated in his keynote address, our collaboration with IFAD has demonstrated:

First, that our services can be replicated, adapted and scaled in new geographies, and can be scaled up to new target populations in existing geographies;

Second, that we have been able to develop and deploy surveys and A/B tests to quickly and accurately gather and analyze information from users to improve our services and adapt to evolving challenges in near real time; and

Third, the combined capabilities of governments, multilateral organizations and non-profit service delivery organizations can deploy services quickly and at scale, using local talent and shared knowledge and systems.

The full text of Michael Kremer’s contribution is accessible here; Owen Barder’s speech can be accessed here; and a full recording of their presentations, panel discussion and subsequent Q&A is accessible via the video posted at the top of this page.

We envisage this our partnership with IFAD as both a mechanism for recovery from the devastating effects that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on smallholder farmers, and an investment in better ways of delivering agricultural information in the long term.

We are excited at our progress in advancing our systems to complement IFAD’s work in support of poor rural farming families and look forward to further success as we continue to work together to service poor, rural families with valuable and productive information.

Owen Barder, CEO

**UPDATE** On December 15, 2021, the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture canceled the project that had been awarded to PxD by public tender. We continue to work with our regional partners, IICA, and the Government of Brazil to identify complementarities and further opportunities for collaboration.

As those of us in the northern hemisphere return to our home offices after an unusual summer, at PAD we do so cognizant of farmers we serve who continue to navigate a period of escalated uncertainty and precariousness due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At PAD we are motivated and optimistic about the ways in which we can do more to understand our farmers’ evolving needs, and about how we can equip them with empowering information to more effectively mitigate new risks, insulate their households from the pernicious impacts of the pandemic, and promote more efficient and productive agricultural practices.

We excited to commence implementing operations supported by a grant and partnership with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (signed on the 28th of August – see our most recent quarterly report for more information) to support the digital extension activities in Kenya, Pakistan and – a new country for PAD – Nigeria.

We are also excited to be pursuing a new partnership with the Government of Brazil and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture. This new opportunity will scale our digital extension work to farmers in a new hemisphere, on a new continent, and in a new geography, at a time when farmers’ informational needs continue to escalate, and in-person sources of information have become more tenuous.

Watch this space!

Make an Impact Today