Dairy farmers in Kenya are being hit hard by climate change.

The country is seeing increased droughts, and, with dry spells projected to increase up to 27% in severity and heat waves likely to increase in duration by up to 30 days, climate change will continue to exacerbate the multitude of challenges farmers and their families face.

Access to water is key for dairy farmers and is a significant challenge in Kenya, especially in rural areas where the majority of the population lives. 76% of households in rural areas do not have piped water access, and spend an average of 3.5 hours per week fetching water (KIHBS 2018).

Continuous access to clean water is vital for dairy production, with an adult healthy dairy animal requiring about 75 liters of water daily, animals can die without water in 2-3 days. Increased herd movement to water sources impacts cow health and also imposes a substantial time burden, particularly for women and girls, with negative consequences such as dropping out of school.

With changing weather patterns and unpredictable rainfall, rainwater harvesting can provide a sustainable source of water for agriculture and livestock production. This is particularly important in dairy farming, as water scarcity and poor-quality water can lead to decreased milk production and health issues in dairy animals. Large water tanks are an efficient method for storing harvested rainwater.

However, financial constraints limit smallholder farmers’ ability to invest in rainwater harvesting tanks for climate adaptation and improved dairy productivity. Lack of access to credit, limited financial resources, and competing household expenses are major barriers to investing in water storage tanks.

Against this backdrop, PxD’s program on Asset Collateralized Loans (ACLs) for water tanks presents innovative financing mechanisms to address water scarcity and liquidity bottlenecks to improve climate resilience and dairy productivity in developing countries.

How dairy ACL works

Water tanks pose a unique financing opportunity. They are large and difficult to move, and they retain their market value over time, meaning the assets themselves can serve as the collateral for a loan.

This removes the need for guarantors, which often poses a significant barrier to access to credit. Repayment is made automatically from the milk income earned through milk sales from the farmers throughout the month. If the farmer was to default on the loan, the tank could be resold at close to the original value.

About 1.8 million smallholder farmers depend on dairy farming for their livelihoods in Kenya but a bulk of them are unable to obtain loans from traditional lenders, such as banks, because they do not have the collateral or credit history required.

The ACL approach, therefore, has several advantages over traditional lending methods, which often require extensive paperwork and collateral that many smallholder farmers do not have.

Our Research Project

PxD has been implementing a two-year research project on ACLs for water tanks in collaboration with the University of Chicago’s Development Innovation Lab (DIL) and two dairy cooperatives (Lessos and Sirikwa Dairies) in Kenya’s Rift Valley region.

A previous study (Jack et al., 2019) demonstrated strong evidence that the ACL model for water tanks could improve farming and household health, as well as well-being outcomes among smallholder dairy farmers.

The study, conducted in partnership with the Nyala Savings and Credit Co-Operative Society (SACCO), randomly offered some farmers the opportunity to replace loans with high down payments and stringent guarantor requirements with loans collateralized by the asset itself.

At the end of the study, default rates were extremely low (less than 1%). Milk sales to the cooperative increased by 6-10%. And, because of the increased water supply within households, girls spent 19% less time fetching water, and school dropout for girls decreased by 85%.

This new study aims to evaluate the impact of ACLs for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. The main outcomes of interest include milk production and milk sales, loan performance, dairy farming practices, water use, time use (particularly for girls and women), household welfare, and well-being.

Delivering tanks to farmers

In partnership with the dairy cooperatives, PxD identified farmers that are eligible to receive the water tanks.

Eligible farmers need to pay an upfront deposit (currently 20%) to receive the tank, followed by monthly loan repayments over a two-year period. Farmers can choose between a 2500-liter or a 5000-liter tank depending on their needs. They receive the tanks at their doorstep for free, with a water tap that is ready to install. Starting from January 2023, PxD rolled out the tanks to a small group of 100 farmers. As of mid-March, 15 farmers had received the tank.

Farmers like Philip Too, a farmer from Sirikwa Dairy who has four dairy cows. Most of the people in his village rely on wells for their household water needs but unfortunately, they do not have sufficient water storage equipment. He is one of the few lucky farmers who are connected to electricity and thus he intends to fill his tank with water from a well within his farm using an electric water pump. With the tank, he hopes to have enough water to not only meet domestic needs for his family and livestock but also irrigate his small kitchen garden from which he expects to fetch some income by selling surplus vegetables to his neighbors.

Esther Sambai, a farmer from Sirikwa dairy, decided to get a 5000-liter capacity tank instead of a 2500-liter tank to meet the needs of her household and neighbors. She said, “My well does not dry up and many people in my village get water from my household for free in the morning when I am at home. As you can see, we pump water directly from the well and therefore I decided to get a bigger tank so that I can store enough water for my family and neighbors. With a tank, my neighbors will be able to access water even when I am away. I will also use the tank to supply water to my animals.” Esther has a solar-powered pump but before the ACL for water tanks, she did not have a water storage tank. The ACL has enabled her to finance a tank easily.

Way Forward

In the coming months, we plan to roll out the tanks to additional farmers (with the goal of reaching 750 farmers in total).

From our early interactions, we have learned that several factors influence take-up including time of the year, competing financial needs such as school fees, and low trust in new financial products which could limit farmers’ take-up of the product.

To address this, we hope to pilot low-risk ways of making the ACLs for water tanks more accessible, such as by lowering the deposit or offering a grace period. We will continue to test similar loan flexibility mechanisms until we can define a product that is interesting, safe, and accessible to farmers across contexts and geographies.

PxD is also making its first foray in Kenya into using low-power radio communications for remote sensing by experimenting with water sensors in this study. These sensors will allow us to measure real-time water levels for dairy farmers so that we can correlate supply, consumption, and dairy output. We hope this paves the way for us to explore the use of other sensors (such as those that measure soil moisture or air quality) to improve farmers’ access to real-time information.

Our first few months of rolling out water tanks have given us insight into the potential for ACLs to enhance credit access for productive assets by reducing the financial burden and collateral obligation that smallholder farmers typically face.

We believe this initiative can have a profound impact on farmers and their families in different contexts struggling with access to water, and could be a path not only to increase profits for farmers and the welfare of their livestock, but improve the well-being of women and girls who are those being most impacted by climate change.

2022 was a tremendous leap forward for research at PxD. Our research and operations teams completed a total of eight A/B test experiments and impact evaluations. We collected data in person and over the phone from approximately 20,000 survey respondents in 27 distinct surveys that took place in Kenya, Ethiopia, Colombia, Pakistan, and three states in India.

We generated new insights to build future programming such as an SMS agro-dealer directory to reduce input market information frictions, built evidence-based proofs of concepts for innovative service design such as WhatsApp-based crowdsourcing chatbot and learned to leverage research partnerships for scalability with dairy cooperatives. We used research insights to shift and refine our approach and we are excited about further impact evidence from forthcoming analysis in 2023.

Devastating events in 2022 from drought in the Horn of Africa to the 100-year flood in Pakistan emphasize that climate change is one of the most urgent challenges facing our users. As such, we have intensified our research efforts to identify interventions that can improve smallholder livelihoods whilst incorporating climate adaptation and mitigation efforts into our existing services. We’ll continue this innovation research agenda in the coming year to explore high-value innovations to supplement our core digital agricultural advisory.

New insights to build future programming

Across a diverse portfolio of research projects, we have demonstrated the value of PxD’s services and contributed to an expanded knowledge base on digital agricultural extension. A particularly promising finding is establishing that digital tools can be effective in improving in-person extension services.

Performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages could increase extension volunteers’ performance: Through a large-scale randomized evaluation in Rwanda, we demonstrated that performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages – particularly goals that were ambitious but attainable – could improve community extension volunteers’ (known as Farmer Promoters – FPs) performance and therefore generate positive impacts on farmers’ outcomes. Sending goal reminders to FPs significantly increased the number of farmers trained by 3.1 percent, led to a significant 4.3 percent more training sessions being delivered, and increased farmers’ registration for subsidized inputs by 1.9 percent (statistically insignificant) over FPs who did not receive goal reminders. Given that the unit cost for each SMS is $0.006 and the average number of farmers assigned to each of the ~14,000 FPs across Rwanda is 190, the effect sizes of these messages are likely to be highly cost-effective.

The results of the Rwanda project support the expansion and replication of extension agent interventions in other settings targeting different populations in the future. In addition, these results point to areas for future research and development that could enhance the effectiveness of extension agent services. For example, we are interested in exploring how digital tools can be used to help extension agents set performance-increasing goals, direct them to farmers most in need, and extend information access to farmer populations that may not benefit from direct digital advisory services.

A digital directory of agro-dealers has the potential to increase the adoption of recommended inputs: In Kenya, we found evidence that farmers can benefit from the provision of an SMS agro-dealer directory by reducing input market information frictions. Our preliminary empirical findings suggest that – particularly for a directory that includes stock and price information about agro-dealers – access to this tool prompts farmers to refine their choice of agro-dealers before an in-person visit. Farmers in the treatment arm who had access to the agro-dealer directory and stock information contacted 21 percent more agro-dealers, but visited 4 percent fewer agro-dealers relative to the control group which did not have access to the tool. This suggests that farmers in this treatment arm used the contact information to call more agro-dealers before spending time and money to travel to the shops themselves.

Farmers given access to the agro-dealer directory were more likely to purchase PxD-recommended inputs and experienced fewer stockouts than those who didn’t have access to the directory. When pooling the two treatment arms, we observe that consistent with PxD’s advisory recommendations, treated farmers were 6 percent more likely than control farmers to use hermetic bags to store maize – a practice shown in rigorous studies like Ndegwa et al. (2016) to prevent post-harvest losses from pests. Farmers in the treatment arm with access to the directory but not stock info appeared to contact and visit agro-dealers at the same rate as the control group but then were 22 percent less likely than the control group to report facing an input shortage when they shopped (meaning they were more likely to find and purchase the product they were looking for).

Building on these promising findings, we hope to identify opportunities to further develop a scalable digital agro-dealer directory tool. Specifically, we are interested in exploring ways to onboard a large number of agro-dealers and update the stock information at a low cost.

Building proofs of concepts

Digital peer groups increase farmer interactions and potentially increase the adoption of recommended practices, but we need creative ways to form groups at a low cost: Various research projects aimed to demonstrate proof of concept for novel interventions that PxD was exploring for the first time. For example, we now have empirical evidence that an intervention in Kenya to organize farmers into groups and send them SMS nudges to communicate with each other was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members. Treatment farmers who were organized into digital peer groups had higher interaction levels than their control group counterparts and were 43 percent more likely to meet with their group members on a farm than control farmers. Interacting with one’s group members on a farm was also associated with increased adoption and knowledge of recommended practices.

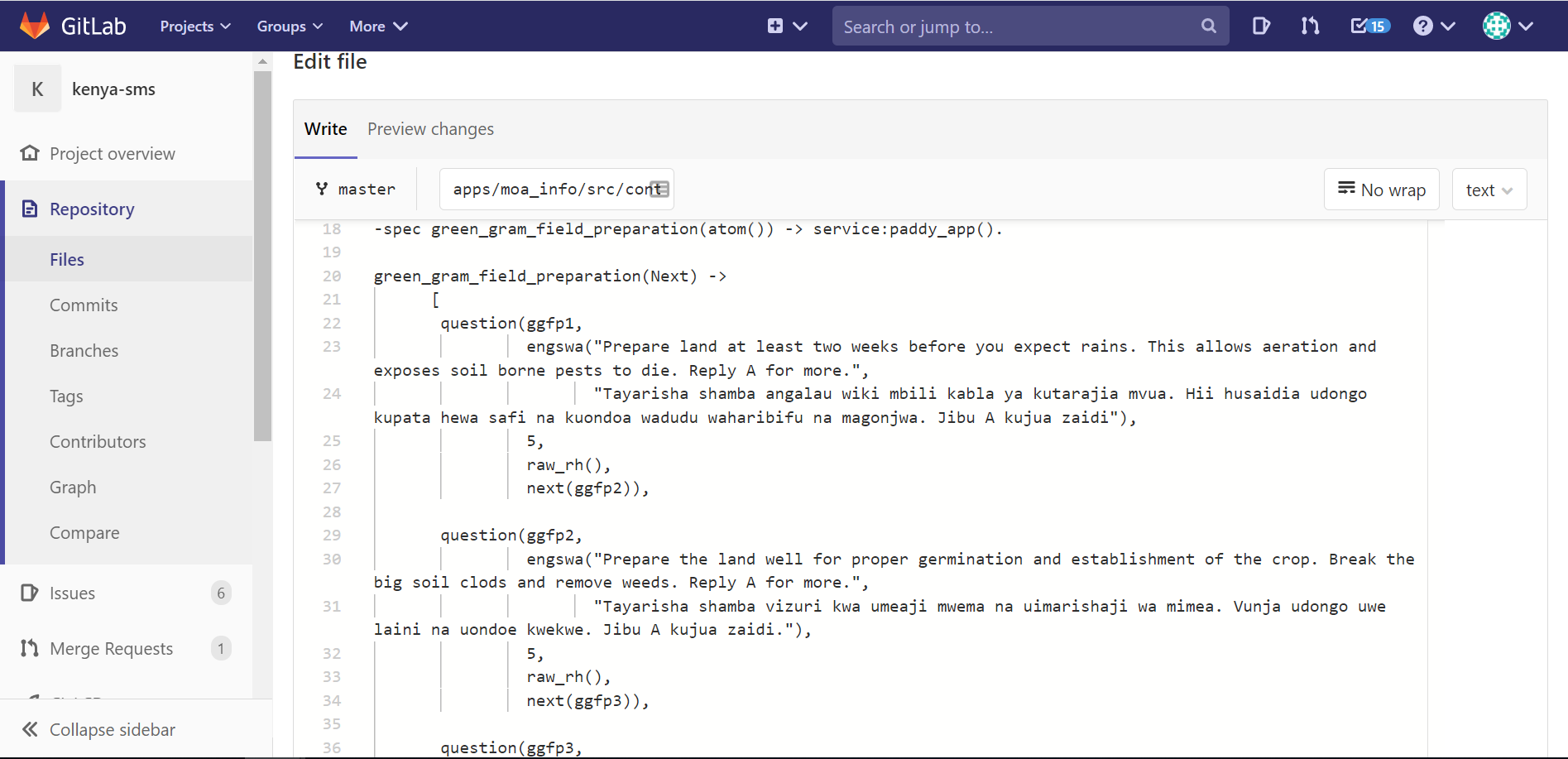

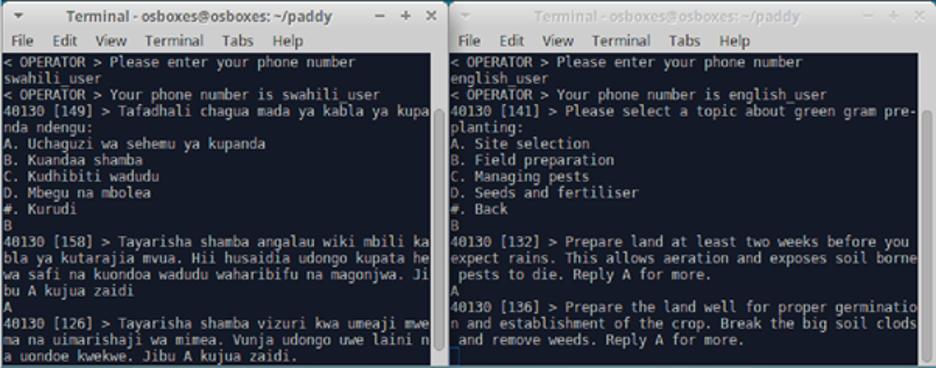

A gig-worker model for crowdsourcing agricultural field photos has the potential to generate real-time data on field conditions: We acquired institutional knowledge, both technical and regulatory, to build and operationalize crowdsourcing platforms to demonstrate the feasibility of crowdsourcing information from agro-dealers and farmers in Gujarat. In a pilot, we set up a WhatsApp chatbot, integrating a WhatsApp Business Account with our in-house user communications platform, Paddy, to guide users through a systematic inspection of a field for crop health issues and send reports back to PxD with their findings.

Eighteen of our recruited farmer agents consistently engaged with the program over 10 weeks, with a median of nine crop health reports per agent. The quality of field reports was high – approximately 94 percent of reports are usable. In total, we received 220 field reports with accurate GPS locations and usable photographs. Each of these reports costs INR 125 (USD 1.67), which is substantially below the cost of a 15-minute phone survey. This suggests that crowdsourced data could be a cost-effective method of collecting local data.

PxD aims to further build this knowledge to crowdsource various types of information and use it to improve future service offerings by customizing advisory to be more locally relevant and actionable.

Working with smallholder farmers in the fight against climate change

We are intensifying our efforts to provide information to smallholder farmers that will allow them to make informed decisions to reduce the risks that climate change presents to their livelihoods and to consider adopting practices that can actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We approach this work with the guiding principle of farmer welfare first: smallholder farmers cannot be expected to pay the price for climate change mitigation. Climate change-related advisory should directly support livelihood gains via improved agricultural output or renumeration .

PxD, in collaboration with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD), worked to assess opportunities to benefit poor farming communities through their participation in climate mitigation activities and to direct tangible returns to participating smallholder communities.

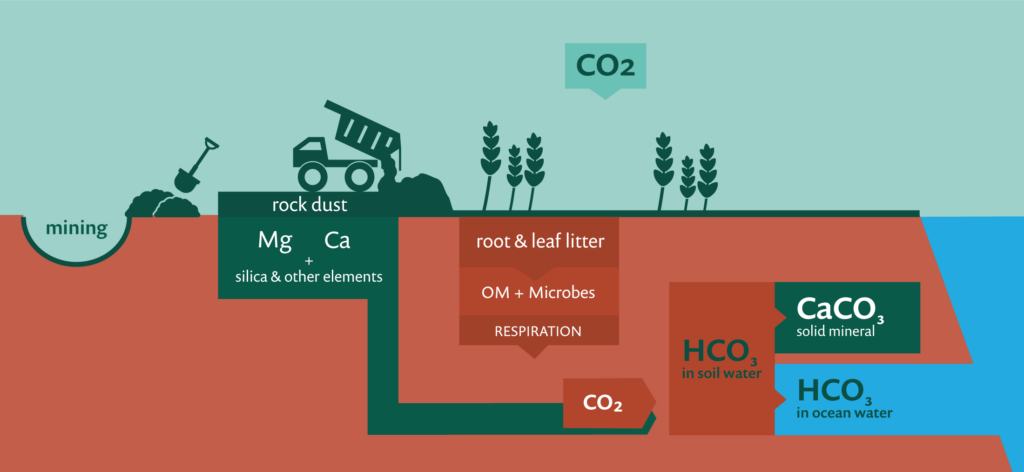

The PxD-IGSD collaboration has focused on exploring four mitigation areas with most promise in agriculture: Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced rock weathering; Carbon dioxide sequestration with organic carbon storage in soils and plant biomass; Nitrous oxide mitigation through precision nutrient management; and Methane mitigation in dairy through improved livestock feeding practices.

- Enhanced rock weathering (ERW), an emerging technology that permanently draws down carbon from the atmosphere and has the potential for agricultural co-benefits makes it an attractive mitigation strategy in the smallholder farmer context.

- There is evidence that conservation agriculture practices that many farmers are already familiar with – such as reduced tillage, the use of cover crops, and intercropping – promote the sequestration of organic carbon in soils.

- In terms of nitrous oxide emissions, simple decision support tools following the Site Specific Nutrient Management approach, i.e. Leaf Color Charts (LCC), have been shown to reduce nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use as well as improve farmer outcomes.

- For methane, improving feeding practices that increase milk production and closing the dairy yield gap in the Global South per cow can lower the methane intensity of production and contribute to methane mitigation, as well as improving farmer livelihoods.

We’re excited to be on the cutting edge of exploring the potential of these climate change mitigation opportunities- like scoping a digital version of Leaf Color Charts to enable the tool to reach a wider scale and Advanced Market Commitments to incentivize R&D for enhanced rock weathering. Our research initiative with IGSD has enabled PxD to identify future activities within each opportunity area to advance climate change mitigation in the smallholder farmer context and we are actively pursuing partnership and funding opportunities to advance these activities.

Learning to leverage research partnerships for scalability

Partnerships have proven to be a critical pathway to increasing impact and scaling evidence-based programs across our project portfolio.

By collaboratively identifying and developing high-impact opportunities with dairy cooperatives in Kenya, PxD has identified a new partnership model in which PxD serves as a technical and analytical partner for innovating and testing service offerings for cooperatives, and builds cooperatives’ capabilities for generating greater impact at scale. We kicked off the partnerships with Lessos Dairy and Sirikwa Dairy by adapting an asset-collateralized loan product for water tanks which has been shown to dramatically increase access to water tanks among dairy farmers in a research study (Jack et al, 2022) and setting up an evaluation to measure its impact on economic and household outcomes.

In Gujarat, India we surmise that identifying low-cost and scalable approaches to crowdsource pest information will require leveraging local organizations and existing social networks for cost-efficient recruitment and training of agents.

To further explore opportunities to support women farmers in Gujarat, we successfully established partnerships that allow us to better understand the constraints women farmers face in engaging in economic activities and their access to information and other services. These partnerships allow us to design and implement group-based digital services to address those specific constraints.

Insights to shift and refine our approach

Our scoping activities allowed us to identify when a change in approach was needed or when interventions did not turn out to be as promising as we had hoped.

In the dairy sector in Kenya, we learned that existing market and coordination failures, such as credit constraints, need to be addressed to create an environment in which digital advisory can effectively improve smallholder dairy productivity.

In testing social learning mechanisms in Kenya, we did not find evidence that the designed intervention increased farmers’ knowledge or the likelihood of adopting recommended practices, despite finding that peer learning was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members.

While subsequent qualitative interviews suggest that some farmers visited the farm fields of their peers and experimented with the recommended practices in a small portion of their plot, developing the digital peer group advisory further is likely to require a substantial investment in basic research to understand farmers’ social learning process and identify creative ways to reduce the relatively high costs associated with forming peer groups.

Finally, we learned to exercise caution in working with established women’s groups in Gujarat in a way that does not exacerbate local power dynamics within communities to ensure PxD’s services are designed in a sensitive way to promote the inclusion of marginalized groups that may face particularly challenging digital access gaps.

Looking forward to continue building our evidence base

In the coming year we are looking forward to continuing to build our evidence base with forthcoming insights on PxD’s impact on farmer welfare from several large-scale RCTs in India, Uganda, and Kenya.

For the impact evaluation of our largest service offered to date for rice farmers in India, endline data collection and analysis are expected following the second season of implementation in 2023. In addition to outcome data on farmers yields and profits, we’re excited to generate additional insights on scalable measurement options for detecting yield changes among rice farmers using remote sensing data.

In Uganda, our work with coffee farmers enabled PxD to explore several dimensions of digital advisory, including comparing a stand-alone digital advisory service to the provision of digital advisory as a complement to in-person training and studying social spillovers from our advisory services. An endline analysis of the effects of this program will be forthcoming in 2023.

We are also excited to generate initial insights on the impact of asset-collateralized loans for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. Using frequent administrative data from dairy cooperatives on milk production, we’ll be able to understand how improved access to water tanks helps farmers mitigate productivity shocks and domestic water shortages as farmers adapt to more dry spells from a changing climate.

In addition to evaluation research with rigorous RCTs, we look forward to building out our research innovation agenda in the coming year. We are exploring a variety of new, evidence-based high-value product innovations that can build on our agricultural impact for smallholder farmers, such as interventions to facilitate market linkages and access complementary financial services. We are committed to using rigorous evidence and deep user research to identify and prioritize which ideas to pursue.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2023! If you’d like to learn more or partner with PxD on specific areas highlighted please get in touch!

From confronting cataclysmic floods in Pakistan, to biblical pest infestations in east Africa, smallholder farmers are on the frontline of an escalating climate crisis. Poor farmers, whose livelihoods disproportionately depend on rainfed agriculture, are particularly vulnerable. The destabilizing impacts of a changing climate will drive many millions of farming families deeper into poverty.

At PxD, we work with millions of farmers to give them the information they need to make more informed decisions about unfamiliar and escalating challenges. We are honored that our MoA-INFO service in Kenya was chosen by the Global Center for Adaptation (GCA) as a case study to highlight the utility of digital information for assisting smallholder farmers as they struggle to adapt to climate change.

In the video below, funded and produced by GCA, Kuboka Maureen, a member of our agronomic team based in Kakamega, is joined by MoA-INFO farmers to explain how the service has assisted Kenyan farmers to navigate climate-related threats.

Given existing poverty, dependence on agriculture for livelihoods, and lack of access to safety nets, poor smallholder families in low- and middle-income countries are particularly vulnerable to exogenous shocks. In March 2020, when the world shut down and told people to stay home to mitigate the public health impacts of COVID-19, many poor smallholder families were left reeling. In response to the growing humanitarian crisis, in April 2020 the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) launched a multi-donor COVID-19 Rural Poor Stimulus Facility (RPSF) to improve food security and resilience among poor rural people during the pandemic.

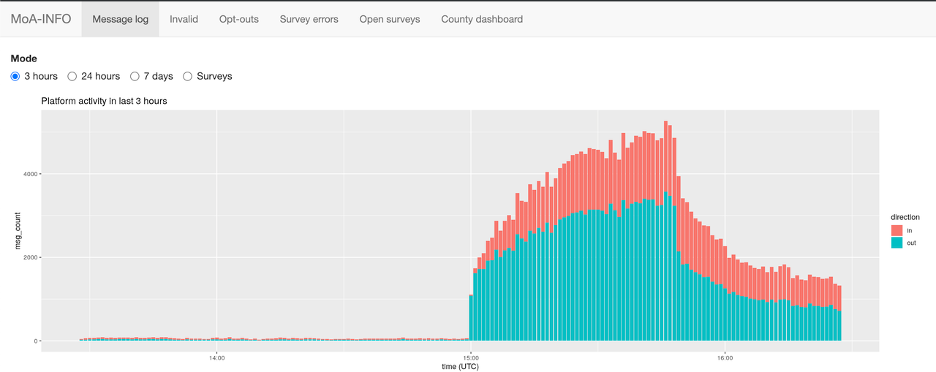

PxD was one of several RPSF grant recipients and interventions selected, all of which focused on either digital services, providing inputs or assets, access to markets, or targeting funds for rural financial services. In collaboration with the IFAD country teams and their government partners, PxD implemented three digital advisory services in Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan between August 2020 and September 2021 to provide digital extension services to approximately two million users. PxD reached 1.2 million farmers in Pakistan, 650,000 in Kenya, and 100,000 in Nigeria, surpassing the initiative’s target of 1.7 million farmers. This includes roughly 178,000 IFAD project beneficiaries across the three countries. These farmers received timely, relevant, and customized agricultural recommendations to improve their farm productivity directly via their mobile phones.

After successfully launching the initial digital services and delivering agricultural advice, IFAD and PxD conducted RPSF rapid assessments in late 2021 to assess farmer outcomes in all three countries. The surveys were designed to compare production, sales, income, food security, and resilience outcomes after the onset of COVID-19 but before the digital advisory intervention (the pre-intervention period) and after the intervention (the post-intervention period). We define resilience as the ability to cope with unexpected challenges and shocks, such as the ability to deal with drought/floods, pest invasions, and rising input prices. The final sample sizes for Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan were 400, 395, and 600, respectively. We stratified the samples by gender, youth status.Youth was defined as heads of households under 35, agro-ecological zone (AEZ) or state1Agro-ecological zones were used in Kenya and Pakistan; the survey covered seven (including unknown) and five AEZs, respectively. We stratified by seven states in Nigeria., and engagement level Kenya and Nigeria only, where we differentiate between high and low engaged users using the median number of messages or calls responded to. so we could analyze and compare outcomes by these subgroups. Within a country, we tested for statistical significance of crop, livestock, poultry, and agribusiness production and sales, as well as food security and income indicators between the pre-intervention and post-intervention period. The samples of farmers selected for the intervention and the surveys were randomly selected from our user bases of IFAD beneficiaries within each country, which may not be nationally representative. Moreover, this is a descriptive analysis, and we cannot infer whether PxD’s services had a causal impact on outcomes reported after the intervention because of the lack of an experimental design (there was no control group).

Farmer-reported outcomes during COVID-19, pre-intervention

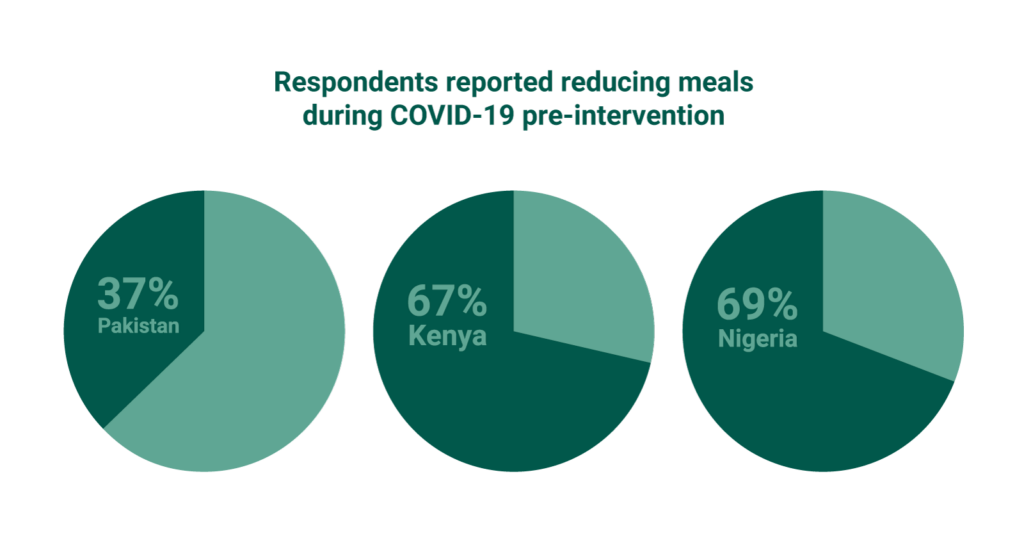

Across all three countries, most respondents reported a loss or reduction in production, sales, number of meals, and resiliency during COVID-19 prior to PxD’s RPSF intervention (pre-intervention period). Respondents from Pakistan seemed to be the least affected by the onset of COVID-19, as fewer respondents reported reductions or losses, compared to Nigeria or Kenya. Moreover, almost half as many respondents reported reducing meals (37%) than in Kenya (67%) or Nigeria (69%). For all indicators except food security, respondents from Kenya reported the worst outcomes, including over 98% who reported lost or reduced production during COVID-19. There was also a wide disparity between the percentage of respondents reporting selling assets across the three countries. Almost two-thirds (65%) of respondents in Kenya reported selling assets because of COVID-19, whereas less than 10% of respondents in Nigeria reported the same.

We also disaggregated production and sales outcomes by specific types of farming that farmers engage in, namely: crop growing, livestock rearing, poultry raising, and agribusiness activities. We find that agribusiness production and sales suffered the most in Pakistan when compared to crop, livestock, and poultry. This finding could be attributed to COVID-19 restrictions which limited the ability to engage in business activities. However, in Kenya and Nigeria, farmers reported larger reductions in crop production and sales compared to livestock, poultry, or agribusiness.

While respondents in Kenya overall seemed to fare the worst in the pre-intervention period, Kenyan women suffered disproportionately more. For example, all Kenyan women reported a reduction or loss of production during the pandemic, and women reported higher reductions than men for all other indicators. We don’t see the same clear pattern in Nigeria or Pakistan, although more women from all three countries reported worse food security outcomes than men. This could in part be due to cultural expectations of women eating last and in small portions, compared to men in the same household.

… and post-intervention

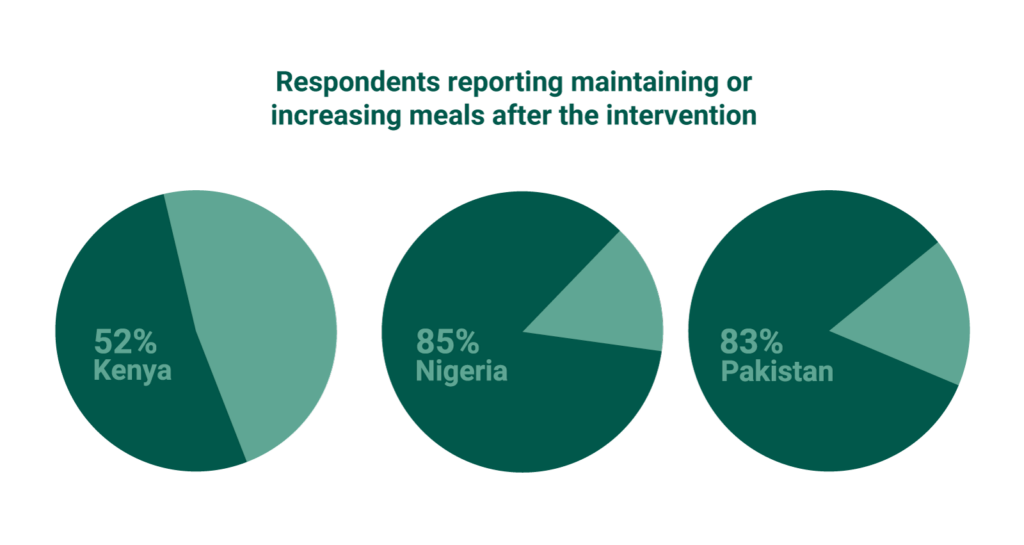

After the RPSF intervention concluded in late 2021, during a lull in the COVID-19 pandemic between the Delta and Omicron waves, we observed encouraging evidence of improved farmer resilience. Respondents in all three countries indicated that conditions had improved relative to the early phase of the pandemic, at the onset of COVID-19 but before the digital advisory intervention (the pre-intervention period), however, some fared better than others. For example, Nigerian respondents reported maintaining or improving production, sales, income, meals eaten, resilience, and asset indicators at higher rates than those in Kenya and Pakistan. Considering the poor conditions they reported during COVID-19, we take this as a sign that Nigerian respondents may have recovered from the pandemic more quickly than their counterparts in Kenya and Pakistan. Conversely, in addition to suffering the worst outcomes in the pre-intervention period, Kenyan respondents indicated that they maintained or improved outcomes the least in the post-intervention period. Only about half of Kenyan respondents reported production and meals were maintained or increased, and less than half reported maintaining or increasing sales, income, resiliency, and assets. Only 25.5% of Kenyan respondents reported income stayed the same or improved, highlighting that Kenyan farmers have struggled significantly in recovering from the pandemic, even after receiving the intervention.

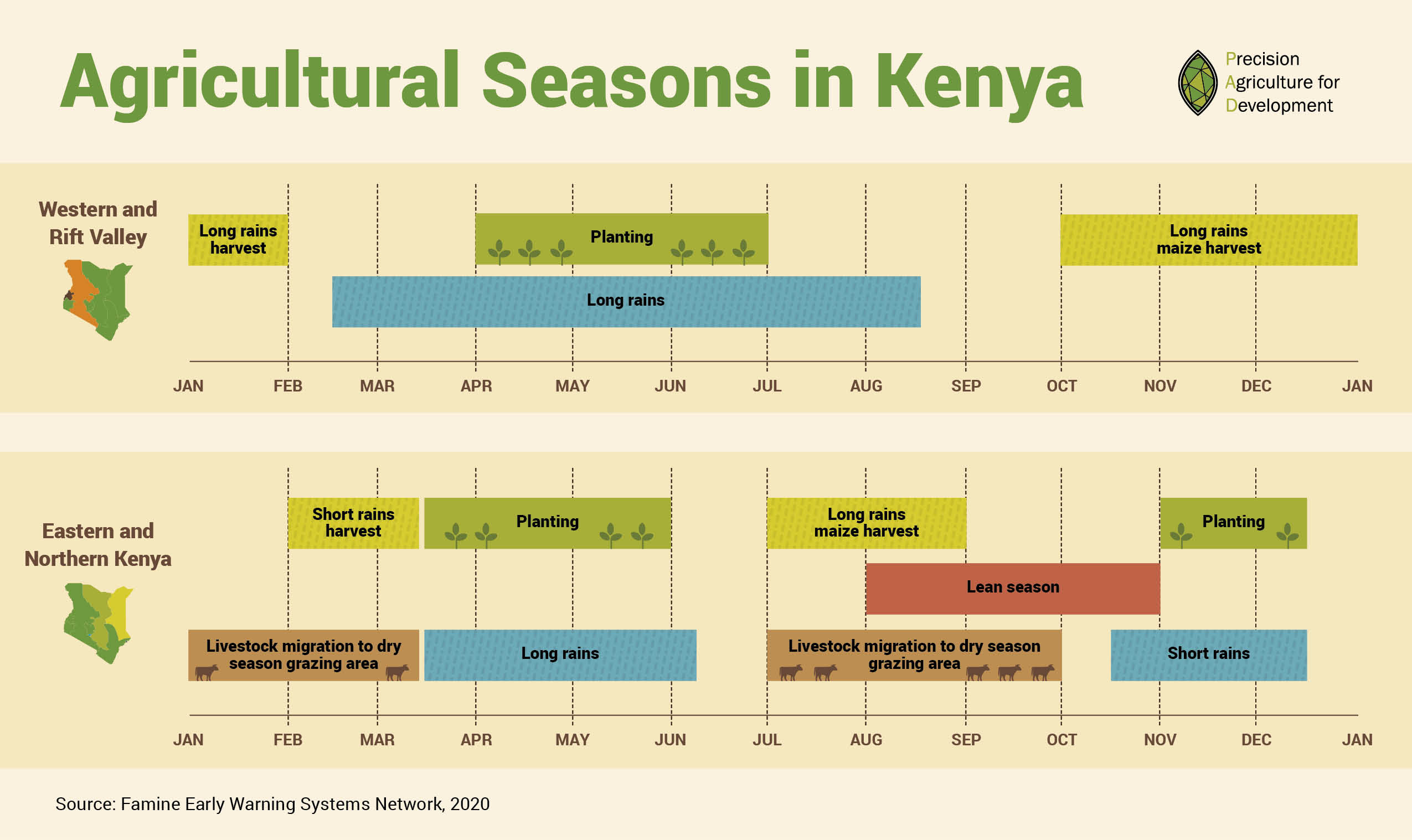

Kenya experienced severe drought during the long rains 2021 season (February-March to June-August depending on location) while the RPSF intervention was underway and during the collection of this data, which likely contributed to the poor outcomes reported after the RPSF intervention. For example, many farmers reported failed crops rendering it impossible to follow the customized digital advisory of the intervention, and to harvest and sell their crop. This is corroborated by reports estimating reduced crop production of up to 70% in Kenya during the drought2Oxfam International, 2022 https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/many-28-million-people-across-east-africa-risk-extreme-hunger-if-rains-fail-again.

Disaggregating the results by type of farming activity, we find that Kenyan and Pakistani farmers reported production and sales reductions in agribusiness the most, even after the RPSF intervention. Because COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the government persisted during the intervention and survey period, we suspect that these restrictions played a role in farmers’ ability to engage in agribusiness, resulting in lower production and sales than other farm activities. In Nigeria in the post-intervention period, farmers reported reductions in production and sales for crop farming more than the other surveyed farm activities, suggesting that even though there were improvements to production and sales after the intervention, farmers’ crop yields suffered the most, relative to their livestock, poultry, and agribusiness activities.

In Pakistan, we observe better outcomes than in Kenya, although slightly less than half (48%) of respondents indicated they maintained or improved their income after RPSF, and only slightly more than half (57%) reported maintaining or improving their sales. Greater than expected wheat yields might have contributed to the better outcomes observed in Pakistan. But while these figures are somewhat encouraging and indicate that some Pakistani farmers were able to recover from COVID-19-related shocks, it also indicates that a significant share of farmers has not recovered. This could be because of the lingering effects of COVID-19 such as global trade shocks and new variants disrupting economic activity via additional lockdowns.

Similar to the outcomes reported during COVID-19, Kenyan women respondents indicated they maintained or improved outcomes less than their male counterparts after the intervention, across all indicators except assets. Only 17.3% of women reported maintaining or improving their income after RPSF, which is almost half the proportion for men, highlighting the predicament of women in Kenya in the face of COVID-19 and drought-related shocks. In Pakistan, while overall outcomes were better, we still note women reported maintaining or improving production, sales, income, and meals at lower rates than men. In Nigeria, a higher proportion of women actually reported maintaining or improving income, meals, and resiliency, and for the other indicators, women reported maintaining and improving at similar rates to Nigerian men. However, we also found evidence that women were disproportionately affected in the livestock sector; Nigerian women were more likely to report reductions in livestock production and sales after RPSF, compared to their male counterparts. Across all three countries, women reported faring worse than men in maintaining or increasing sales.

We also disaggregated the post-intervention RPSF results by farmers’ level of engagement with the PxD service, where we defined highly engaged users as having picked up or responded to more than the median number of calls (Nigeria) or SMS messages (Kenya)3We did not disaggregate by level of engagement in Pakistan.. In Kenya, we did not see any clear patterns by engagement level. However, in Nigeria, we found that highly engaged users (who picked up more than seven calls) reported maintaining or improving production, sales, and income at a higher rate than lower engaged users. This result provides suggestive evidence to our theory of change that users who more actively engage with our services may implement more of (or implement better) our recommendations, leading to improved outcomes.

It was challenging to draw clear conclusions from the data at the level of agro-ecological zone and state, due to the small number of respondents per zone or state. For example, in Kenya, there is some evidence that households from the upper highlands (UH) AEZ fared better than respondents in other zones. This may be because the UH zone was less affected by severe drought than other more arid regions in the country. In Nigeria, respondents in Katsina fared worse than the other states, reporting the highest level of reductions in most production, sales, food security, and resiliency measures. We suspect that local terrorism and banditry in the state played a role in the poor outcomes reported there. Meanwhile, respondents in the Nigerian state of Jigawa reported faring the best, which may be because widespread telecommunication shutdowns that plagued the country during the grant period were avoided, and the state is relatively peaceful compared to others in the north.

While the initial COVID-19 shock occurred in early 2020, the results of the surveys suggest that there are strong lingering negative effects in all three countries (as well as other severe shocks such as extreme weather events and terrorism) and more direct support is needed to return smallholder farmers to their pre-COVID-19 state. While this analysis does not estimate the causal impact of PxD services, we plan to use the data from this analysis to improve our services to more effectively meet farmers’ needs. In Kenya, we hope to specifically address weather-related shocks such as severe drought. Weather-related services are already being explored in Pakistan and India and learnings from these pilots might also be applicable in Kenya. Based on the evidence that women found it more difficult to cope and recover from COVID-19, we hope to develop women-targeted interventions designed to reach more women users or develop content tailored to women’s needs. This will build on gender-focused service experimentation we have undertaken such as providing messages with a female narrator and nudges encouraging spouses to share PxD advisory with each other, as well as implementation of advisories focused on female-dominated value chains such as kitchen gardens, dairy, and livestock.

Since the conclusion of the intervention and endline survey, farmers’ situations have become even direr. Experts warn of rising food shortages and hunger due to high global inflation and supply chain disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine. The World Bank estimates that the Agricultural Price Index is 14% higher as of this June compared to January and 94% of low-income countries are experiencing food price inflation greater than 5%. The already looming food crisis is expected to be exacerbated by a sharp increase in fertilizer prices, largely driven by the war in Ukraine, as Russia and its ally Belarus produce 40% of the world’s supply of potash, and Russia and Ukraine together export 28% of nitrogen and phosphorus-based fertilizers. Within this context and amid the backdrop of the ongoing pandemic, the need for strong support for poor smallholder families is urgent.

Women play important roles in smallholder dairy production. As PxD prepares to roll out a dairy advisory initiative in Kenya, we conducted a gender survey to better understand the division of labor within households. In this post, the second of a two-part series, Sam Strimling, Research Associate, presents an analysis of the results. The first post laid out the importance of understanding the specific needs of women in designing effective service delivery for women.

In many smallholder households, labor relating to the tending of livestock – particularly dairy animal husbandry and dairy production – is derived disproportionately from women. This culturally entrenched division of labor has direct implications for PxD as we expand into supporting dairy farming activities and seek to target our digital advisory services appropriately.

There is a plethora of evidence – much of it detailed in the excellent book, Invisible Women, by Caroline Criado Pérez – of service providers who failed to understand women’s specific needs and preferences and thus designed inferior products. Providers of digital advisory services are no exception to this disappointing phenomenon.

As PxD prepares to roll out a dairy advisory initiative in Kenya, we considered it a top priority to conduct a gender survey to better understand the roles played by each household member with a focus on tasks performed, decision-making, and financial agency. The results of this survey will be used to inform the dairy content we are developing as part of an upcoming randomized controlled trial (RCT) we are implementing in partnership with several dairy cooperatives across different regions in Kenya. We will use the results of the survey to inform the type of content we write, as well as how and to whom we deliver it.

As detailed in a previous blog post about the survey, the PxD Kenya team used a novel and rich dataset to inform survey design. In addition to gaining insights into the roles played by different members of the household, we also sought to better understand the technical and analytical abilities of each respondent, as well as perceived technical knowledge for each household member. Finally, we used methods from behavioral economics to empirically evaluate trust within the household.

Survey Structure

We started with a total sample of 600 households randomly selected from two dairy cooperatives, in the Rift Valley and Eastern regions. The sample was stratified by geography, milk sales to the dairy, and deductions for purchases from the dairy-affiliated agrovet (in which farmers are able to purchase animal medicines and farming inputs using income from milk).

We called 464 unique respondents, of whom 357 answered at least one call. Respondents who lived with or made decisions with their spouses were asked to provide contact information. Single respondents – many of whom were widows or widowers – were encouraged to complete the survey, but were not asked a series of subjective questions about the degree to which they made decisions or discussed activities with their spouses. Single respondents were also not asked to participate in the public goods game. In total, 114 spousal pairs completed the full survey. These spouses, and their respective households, will be the focus of this post. The demographics of the survey respondents and their households are shown in the table below.

Intra-household dairy roles. At the start of the survey, each respondent was asked to list the members of the household above the age of five, and state their age, gender, and education. The survey enumerators used tablets to record responses that allowed them to capture this information to be used later in the survey. Respondents were then asked to select from this list to indicate which member(s) of the household:

- Practiced crop farming, grazing, fetching water, wage employment [Respondents were specifically asked if they held “a job outside the home.”], schoolwork, childcare, and/or leisure in any given week. Respondents were also asked to indicate the number of hours each selected household member spent on each task in a typical day.

- Practiced various dairy tasks, selected from a list of tasks generated by our Staff Dairy Livestock Expert. For each task selected, respondents were asked to indicate which household member took primary responsibility, and how many minutes this individual typically spent on that task per day. This is the only household roster question for which the respondent was asked to select a single respondent rather than having the option to select multiple members.

- Were knowledgeable about nutrition, artificial insemination, hygiene, disease, and feed and fodder. The respondent was also asked to rank the selected household members in terms of their knowledge on that particular topic.

- Had taken various financial actions, including purchased a personal asset, purchased a productive asset, sold crops on behalf of the household, received payment for crops on behalf of the household, received payment for milk production, and made decisions about spending dairy income.

Analytical ability and dairy knowledge. Respondents were asked to answer a series of scenario-based analytical questions as well as questions to assess technical dairy knowledge on a broad range of topics. We then calculated the percentage of analytical and technical questions the respondent answered correctly.

Subjective assessment of financial agency and cooperation. Respondents were also asked to provide information on their personal knowledge and feelings of financial agency. To assess financial agency, respondents were asked to indicate using a Likert scale the degree to which they discussed finances with their spouse, trusted their spouse’s financial decisions, talked with their spouses about agricultural work, and talked with their spouse about their day generally.

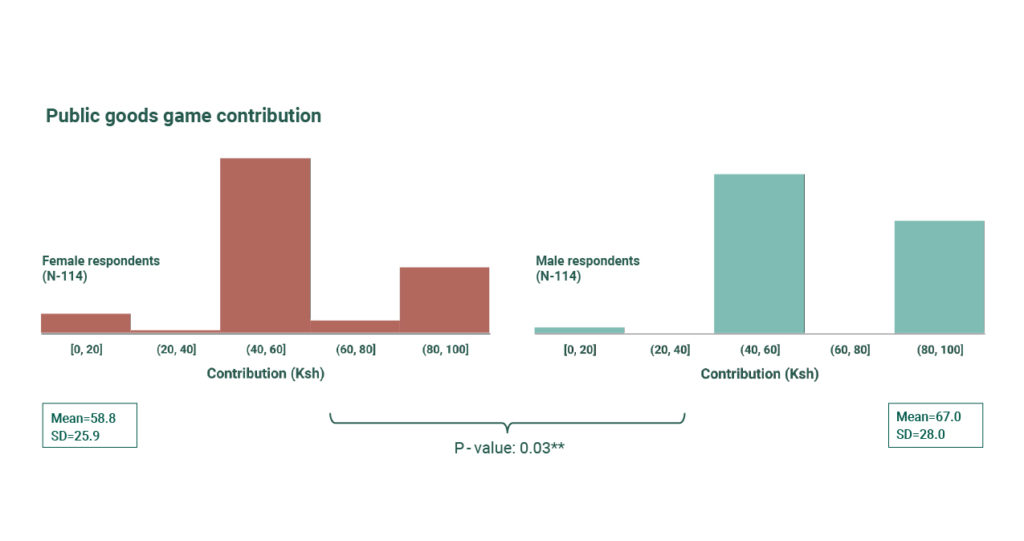

Intra-household cooperation – the public goods game. Finally, all respondents who completed the survey were awarded 100 Ksh (approximately $1) in airtime, and – if their corresponding spouse had also completed the survey – they were invited to increase their earnings by contributing some portion of their earnings into a common account with their spouse. Since the amount contributed to this common account was doubled and then split evenly, the respondent’s contribution could be interpreted as an empirical measurement of cooperation with their spouse.

Information asymmetry. For the 115 households in which we collected information from both spouses, we were able to calculate the degree of coherence in their responses in terms of the intra-household (inter-spousal) correlation coefficient.

General Time Use & Dairy Tasks

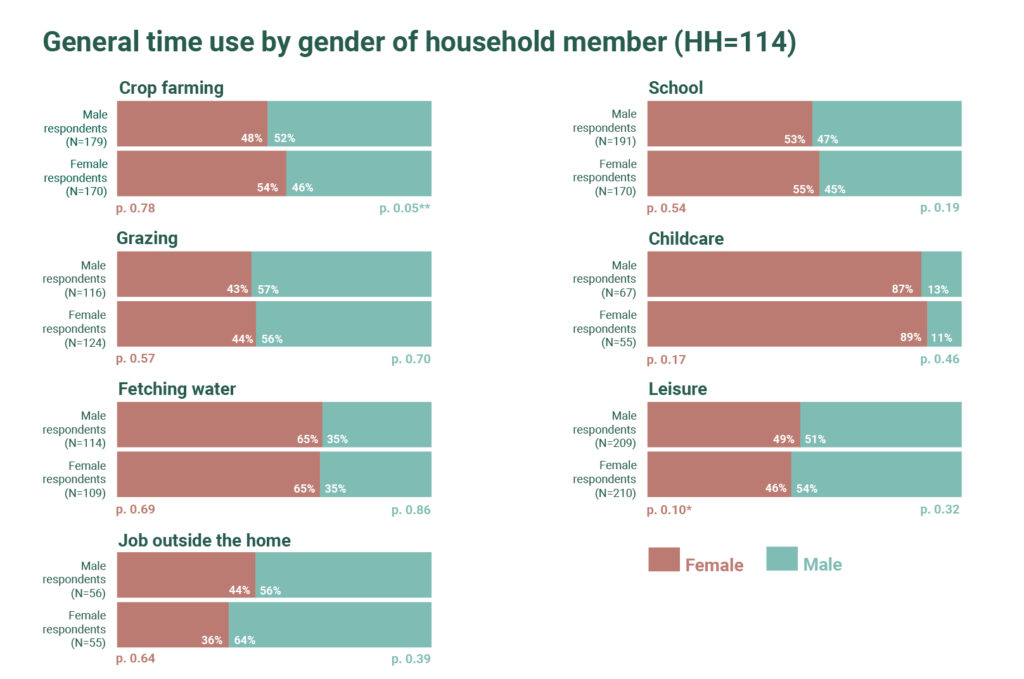

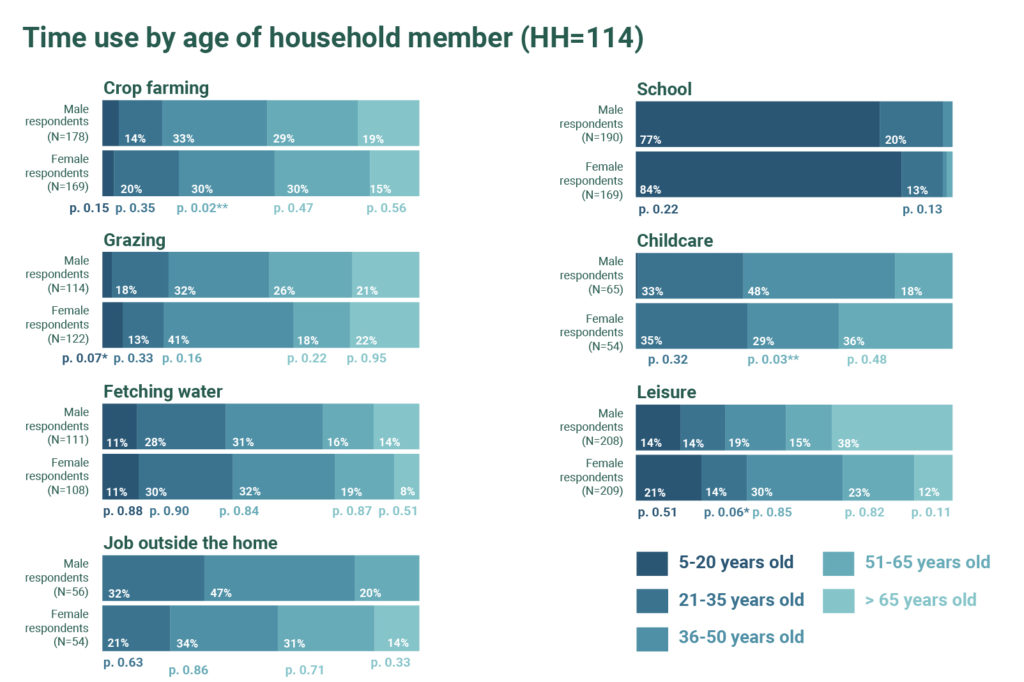

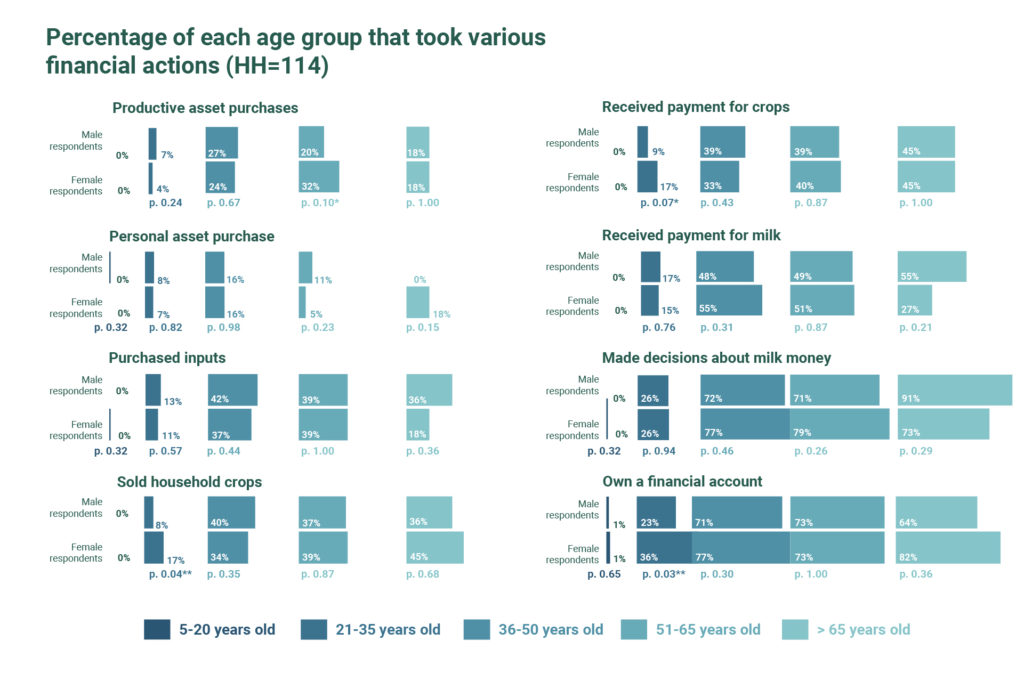

Male and female respondents broadly agreed on the division of labor within the household by gender of household members. We focus our description of intra-household gender-specific roles on the share of time spent by males and females within the household and checked whether men and women respondents generally agree on this proportion. This is presented in Figure 1 below, which organizes respondents’ perceptions by the proportion of hours household members of different genders spend on pre-specified activities within the household (p-values reflect tests of the null that there is no difference in responses across spouses). While male and female respondents differed in their reports of the time spent by gender of the household member, these differences were not significant for any time-use category other than crop farming. In this instance, the difference in perceived hours on task from the perspective of male and female respondents was statistically significant at the 5% level (as demarcated by the p-values next to each bar). In general, respondents of both genders reported that crop farming, grazing, school, and leisure were split nearly evenly by gender. Female household members, however, were reported to spend more time fetching water and engaging in childcare relative to male household members, and male household members were more likely to have a job outside the home.

There was an overall alignment between male and female respondents on the reported activities of different age groups (Figure 2). The overwhelming majority of those in school were aged 5-20, while those aged 26-50 performed the bulk of income-generating labor, including crop farming, tending to grazing animals, and jobs outside the home, as well as tasks culturally associated with “women’s work” (fetching water and childcare). Leisure was fairly equally distributed across age groups.

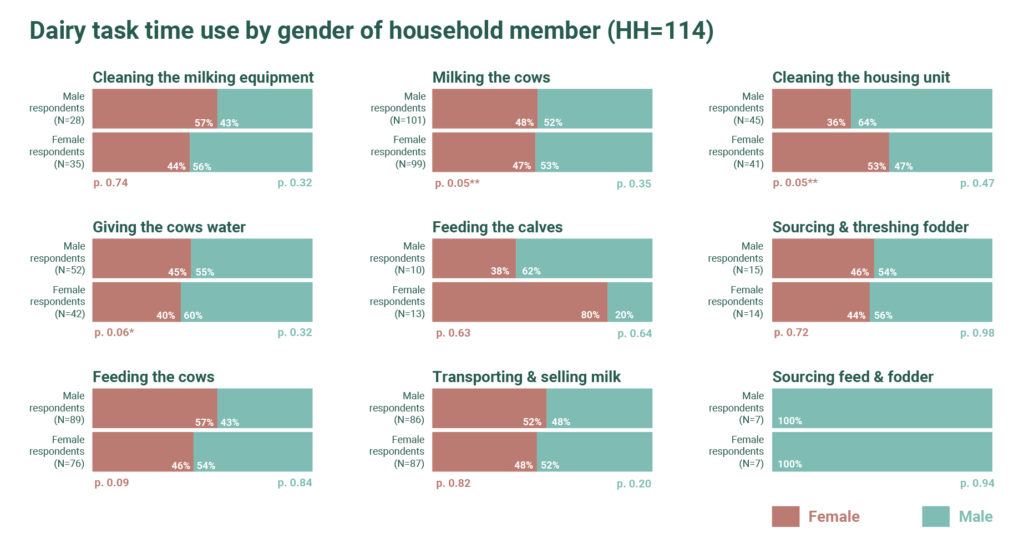

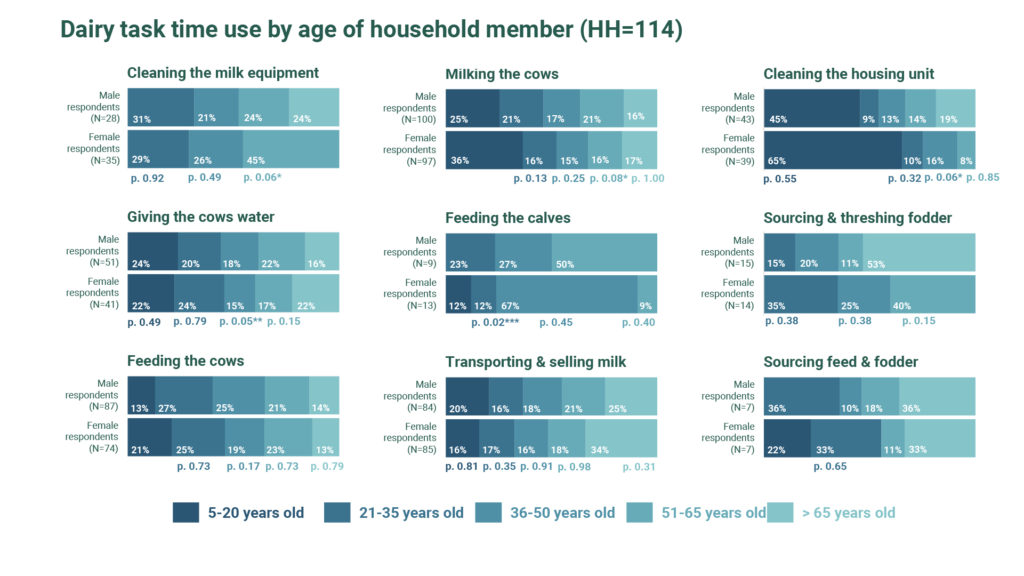

Of the 20 dairy tasks that each respondent was able to select from, nine were selected by respondents in our sample: cleaning the milking equipment, giving the cows water, feeding the cows, milking the cows, feeding the calves, transporting and selling milk, cleaning the housing unit, sourcing and threshing fodder, and sourcing feed and fodder. Figures 3 and 4 below applies the same analysis to these tasks as applied above to the responses on household time use: that is, Figure 3 analyzes the differences in male versus female respondents’ perceptions of household members’ dairy time-use by the gender of the household member, and Figure 4 analyzes this in terms of household member age group.

For most tasks, labor appears to be split fairly evenly by gender. A possible exception to this rule is feeding of calves, which female respondents assert is performed more by women than by men at a ratio of 4:1; men disagree on this, however, which is statistically significant at the 5% level, though the relatively low sample size makes it hard to put too much stock in this comparison. Further analysis could examine whether there is a difference based on a household’s production system. For example, in zero-grazing (or semi-zero-grazing) households, domestic tasks may account for a larger share of household labor, in turn skewing labor allocation toward the purview of women.

In addition to splitting labor by gender, dairy-related labor also appears to be distributed relatively evenly across age groups. The exceptions to this rule are “feeding the calves” and “cleaning the housing unit,” which according to female respondents – but not male respondents – is overwhelmingly performed by younger populations. Though difficult to say conclusively, a possible explanation for this difference in reporting is that female respondents may be more aware of how labor is divided on these tasks, which tend to be domestic in nature.

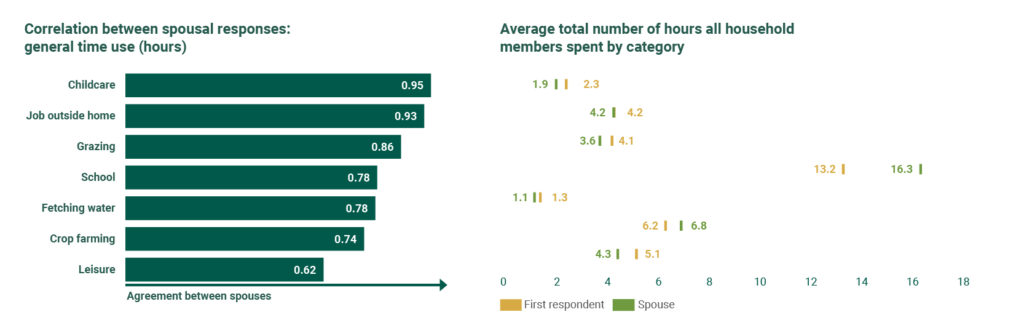

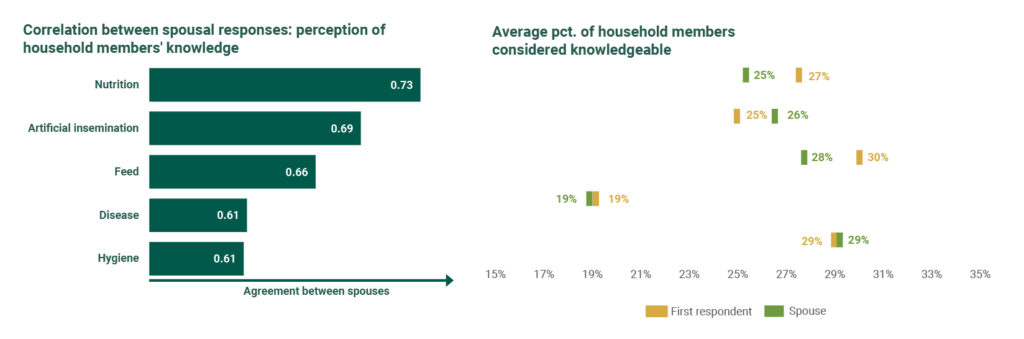

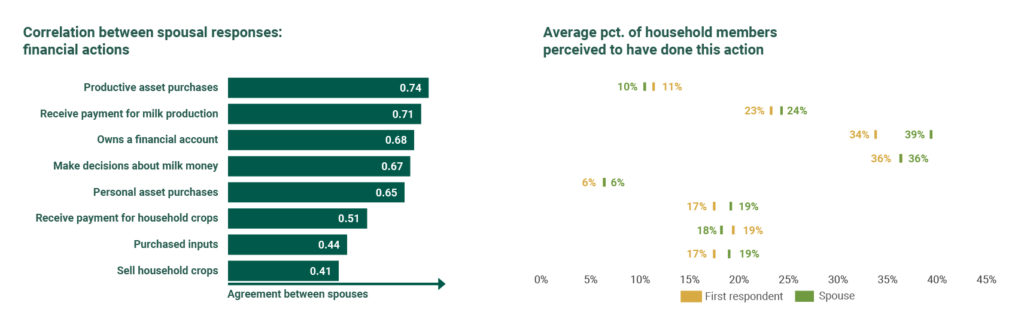

While on average there seems to be a great deal of agreement between spouses in our sample, this does not preclude the possibility of variation in the degree of agreement across households. Figure 5 below displays a measure of within household agreement by calculating the correlation coefficient in the vector of responses provided by women and men respondents in the same household. If, for example, on average, most husband and wife pairs agree on the time spent within the household on childcare, the correlation coefficient will be closer to 1. If they systematically disagree, the correlation coefficient will approach -1. If the correlation coefficient is close to zero, there is no clear agreement between husbands and wives within the same household on how tasks are distributed among household members. In our survey, there was a high degree of correlation between spousal responses for general time-use categories (i.e., crop farming, childcare, leisure, etc.).

Knowledge

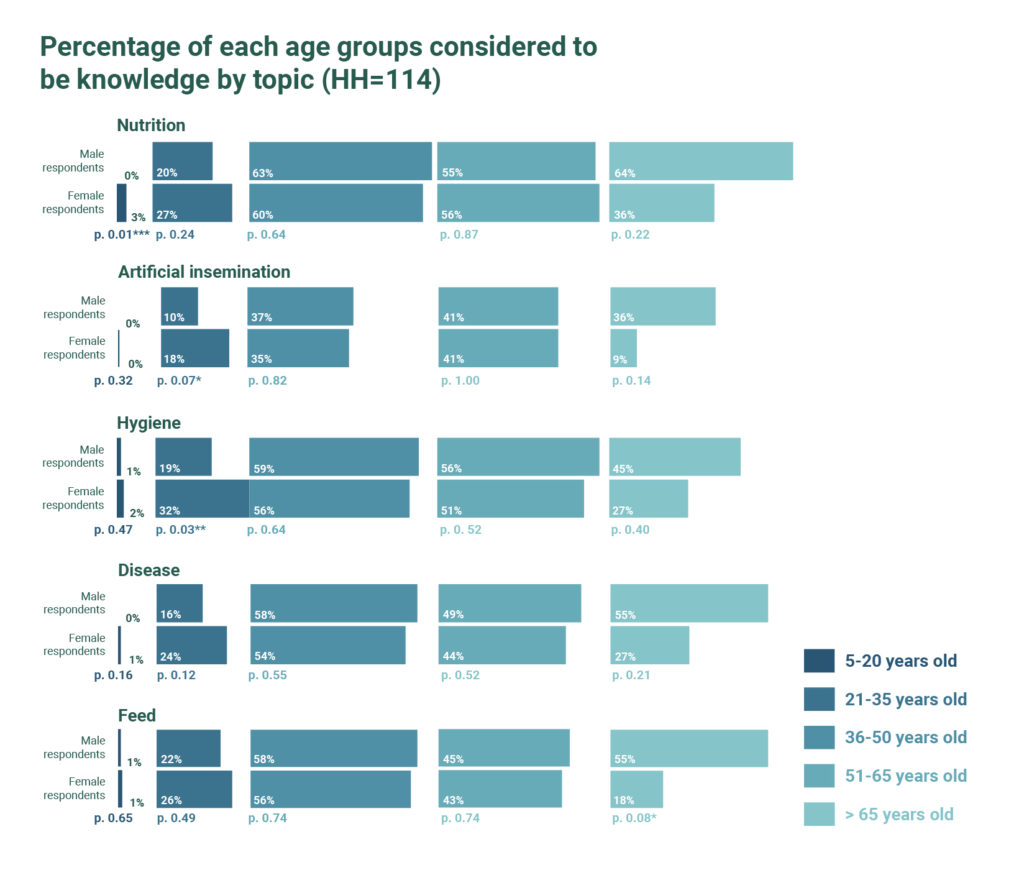

Prior to measuring actual analytical skills and technical knowledge, we asked respondents to subjectively indicate which household members possessed knowledge in five categories: nutrition, artificial insemination, hygiene, disease, and feed. We then calculated the total percentage of individuals within a household perceived to have knowledge on a topic by gender (Figure 6) and age group (Figure 7).

Across all categories, both male and female respondents perceived male household members to be more knowledgeable; there was broad intra-household agreement on knowledge perceptions as well (see Figure 8). Interestingly, male household members were judged to be especially knowledgeable in categories such as disease and artificial insemination; this was particularly true in the eyes of male respondents, who judged male household members to be at least twice as knowledgeable as women about these subjects. One hypothesis for this is that these subjects may carry a connotation of expertise due to their affiliation with actual professionals (i.e. veterinarians). By contrast, the perceived knowledge gap was a lot lower for other categories, such as nutrition and hygiene.

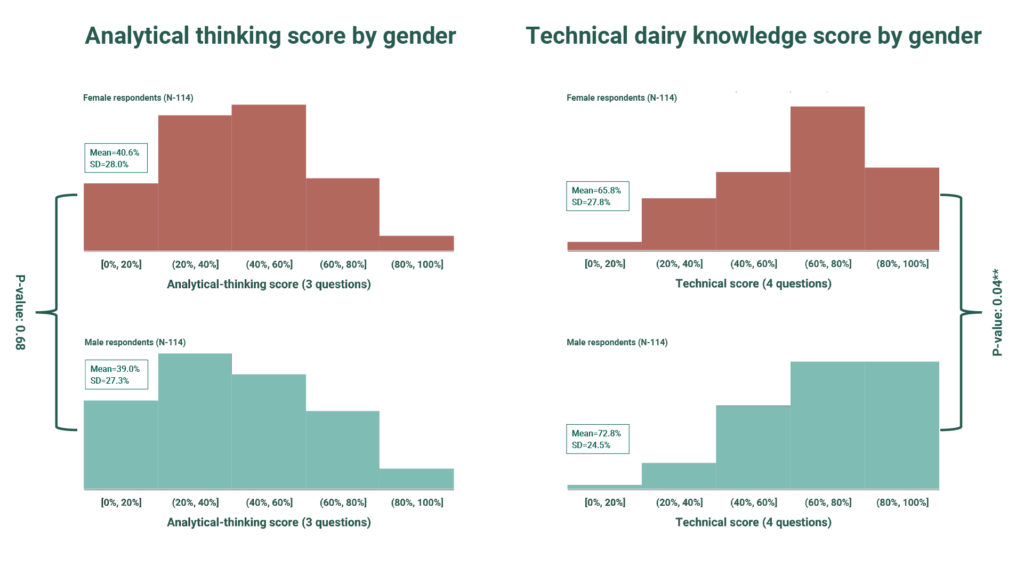

In fact, when tested, male respondents did perform significantly better than female respondents in terms of technical knowledge, with a mean score seven percentage points higher. That said, male respondents performed no better than female respondents on a test that used scenario-based questions to measure analytical thinking.

That said, two caveats must be considered in drawing conclusions from these results (shown in Figure 9): First, these results measure respondent knowledge rather than directly evaluating the knowledge of all household members. Second, the tests were brief and covered a broad array of subjects, making it impossible to evaluate whether the respondent may have deep knowledge on a particular topic. Both of these gaps suggest promising areas for future research in order to better understand the degree to which perceptions of knowledge match reality, rather than merely reflecting cultural biases; in reality, the answer may well be both, though additional empirical analysis is needed to make this claim.

Financial Agency, Intra-Household Decision-Making, and Trust

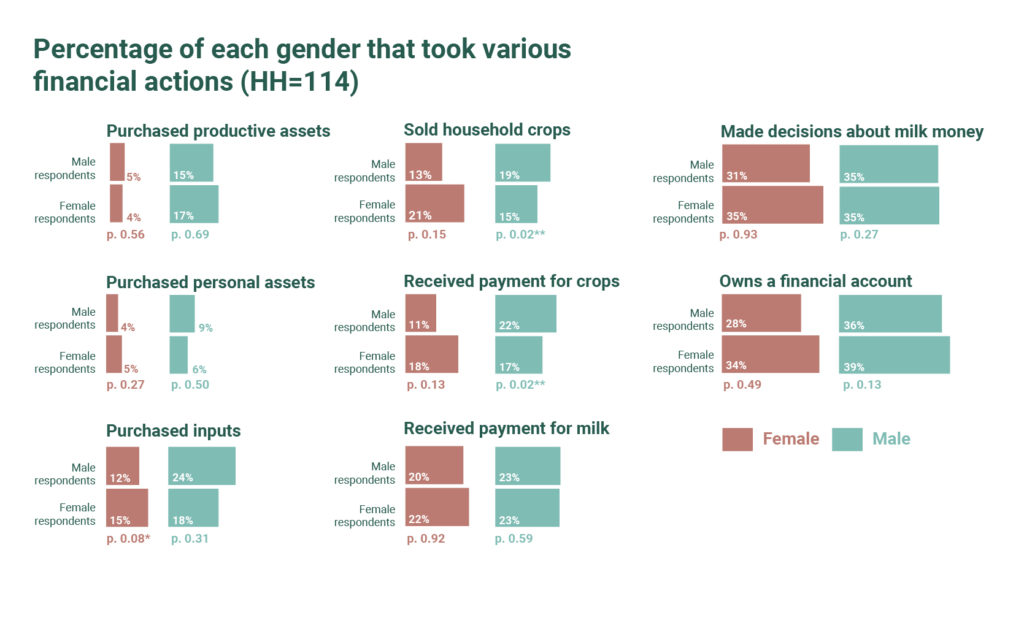

Respondents were asked a series of questions regarding their perceptions about who controlled money within the household: who in the household purchased productive assets, purchased personal assets, purchased inputs, sold household crops, received payments for crops, received payments for milk money, made decisions about spending milk money, and owned a financial account. Figures 10 and 11, respectively, analyze these results by gender and age of the household members.

Very few household members were reported to have purchased personal assets; more – overwhelmingly men – purchased productive assets, according to both male and female respondents. Male and female respondents also agreed that payment for milk money and decisions about milk money were generally split evenly within the household. Both male and female respondents also reported that household members of both genders owned financial accounts (though men did so to a slightly higher degree).

There was less agreement by respondent gender about crop farming. Male respondents reported that male household members played a larger role in selling crops, whereas female respondents reported the opposite. This same pattern was true regarding respondent perceptions of who received payment for crops. In both cases, the difference in the perception of different genders was statistically significant at the 5% level. Additionally, while respondents of both genders agreed that more male household members purchase inputs than female household members, male respondents reported the ratio to be 2:1, while female respondents reported this difference to be marginal; this disagreement was weakly statistically significant (at the 10% level). Within households, there was also comparatively more disagreement on the measures related to crop farming and associated income, as shown in Figure 12.

There are several potential explanations for the disagreement on this measure. One potential reason is there may be an internal lack of clarity within the household about who performed which category of tasks. This does not necessarily mean that individual tasks do not have a “clear” owner; alternatively, the divisions we at PxD made for the purposes of this survey may not correspond to household constructs around the division of finances. This suggests a possible area for future research: an open-ended survey consisting of structured interviews on this topic may yield interesting insights regarding financial accountability and power within the household.

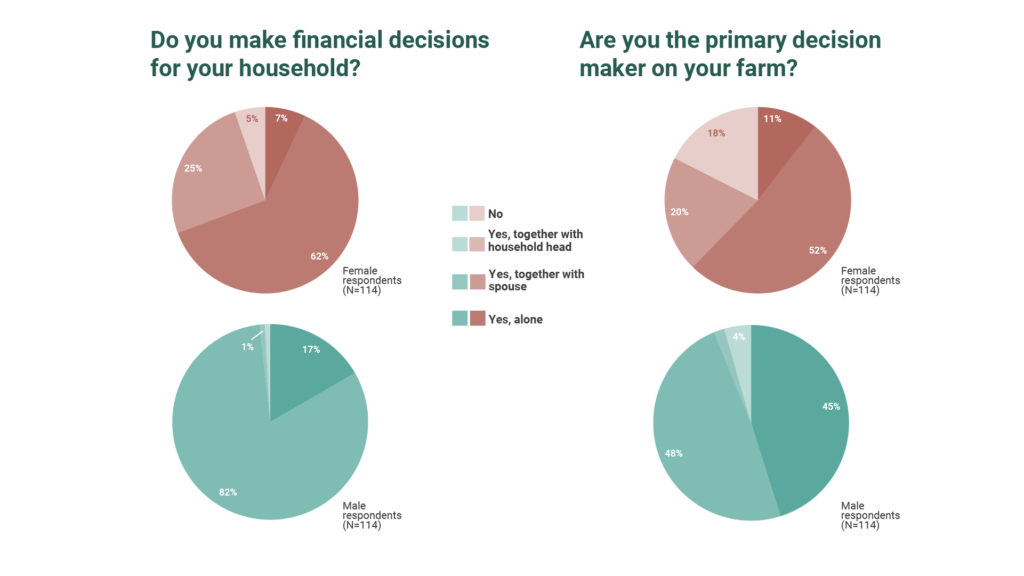

Moreover, the disagreement may reflect the fact that some tasks may be performed jointly (or in an alternating fashion) with other household members; this possibility need not be mutually exclusive with alternative divisions of labor within the household. The results in Figure 13 suggest this possibility. When asked who makes financial decisions about the farm, the majority of women (62%) and men (82%) said they made this decision together with their spouse; an additional 25% of women said they did so jointly with the household head. Even who the “primary” decision-maker was could be muddled, with 72% of women and 50% of men claiming to occupy this role jointly with either a spouse or household head.

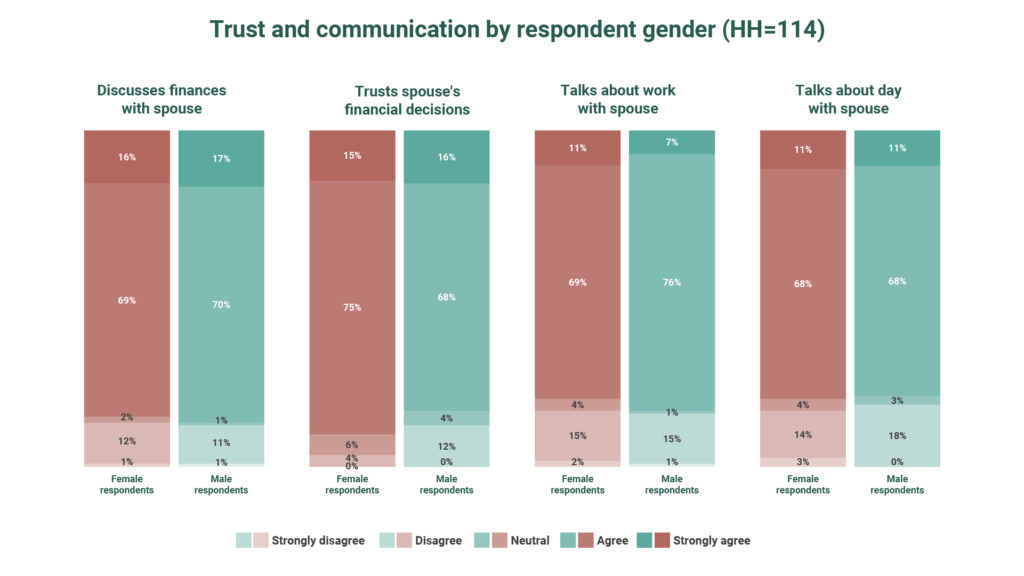

These results are ambiguous regarding whether each decision is made jointly or whether men and women have different spheres of influence within the household (and financial discretion within those spheres). However, the Likert scale questions, in which respondents were asked to agree or disagree with a number of statements about intra-household decision-making suggest that many decisions are made jointly – or at least with a substantial discussion between household members. (Figure 14)

Eighty-five percent of female respondents and 87% of male respondents reported that they discussed finances with their spouse; moreover, 90% of female respondents and 84% of male respondents reported that they trusted their spouse’s financial decisions.

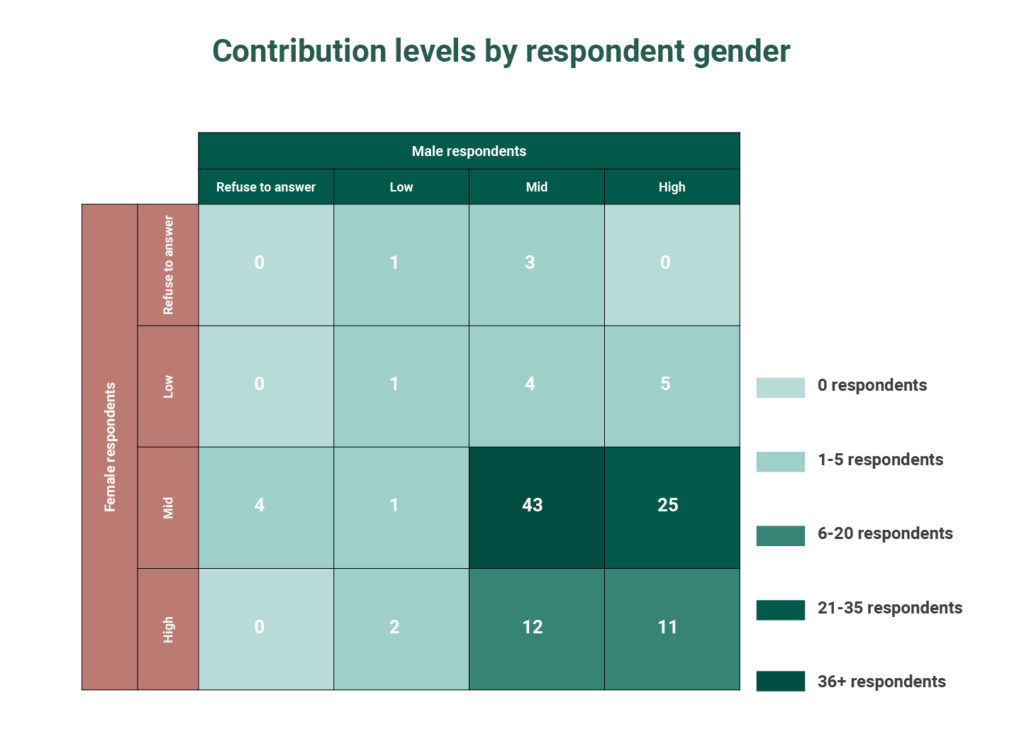

In order to empirically test these subjective responses, we also asked respondents to participate in a “public goods game,” in which they could choose to augment a portion of the financial incentive they earned for completing the survey (100 Ksh, or about 1USD) to a common account. Contributing a greater amount theoretically indicates a greater degree of cooperation with one’s spouse since the amount in the common account was split evenly between spouses after both completed the exercise, regardless of how much each spouse contributed individually. The results of this game suggest a moderate amount of trust, with contributions for both women and men clustering around the midpoint of the range between zero and the total possible contribution. Figure 15 displays the distribution of these respondents’ contributions. While male respondents contributed more on average (statistically significant at the 5% level), the plurality of respondents of both gender contributed a medium amount (i.e., 40-80 Ksh)

One way to empirically evaluate whether the public goods game in practice aligns with subjective cooperation in the household is to directly compare these results. First, we regressed the correlation coefficient between the spouse’s individual Likert responses – that is, the degree to which husband and wife agreed about their level of trust or communication – on the various contribution categories (limited the covariates to the bottom quadrant of Figure 16, to make sure each category reflects a sufficient sample of people to draw meaningful conclusions). The results of this regression are shown in Table 2. There was not a high correlation between these metrics, with none of the contribution categories predicting agreement between the spouses regarding the degree of cooperation.

The next stage of analysis was to compare directly the responses to the Likert scale questions on intra-household communication and trust to the public goods game contributions. To do so, we first split the sample by respondent gender and then ran ordered logit regressions separately for each sample (Table 3). In these regressions, a positive coefficient signifies that a member of a household in that specific contribution category is more likely to “strongly agree” with the statement. To make this concrete, the variable “female mid, male high” in the female sample is equal to one for a member of that population who contributed a medium amount (40-80 Ksh) and whose husband contributed a high amount (80-100 Ksh), and is equal to zero otherwise. A positive coefficient on this variable means that a respondent in this category is more likely to “strongly agree” with an affirmative statement on the Likert response; e.g. for the first regression in the table, she is more likely to say she often discusses finances with her spouse. While all the coefficients for the regressions on the male sample and about half of the coefficient for the regressions on the female sample are positive, none of the results in either sample are statistically significant.

Since the public goods game contributions do not align with subjective measures of intrahousehold cooperation, it is unclear whether respondents are less trusting in practice than they aspirationally report to be on the subjective questions, or whether the public goods game does not accurately measure intrahousehold trust. The answer may be a combination of the two or may vary by Likert category. This suggests an area for future research.

Next Steps

This information is valuable for informing the design and operation of a dairy service that empowers rather than further marginalizes female farmers. It bears mentioning that we will continue to monitor engagement by gender to validate the insights of this survey on an ongoing basis and to make sure that we continue to reach women farmers.

That said, there are a few points we can take away from this dataset –

and we can use it to identify areas for additional research:

- In general, women and men reported that they split labor related to crop farming and grazing, and both females and males reported going to school and pursuing leisure activities. Unsurprisingly, women reported spending more time fetching water and engaging in childcare relative to men, and men were more likely to have a job outside the home. Perhaps more surprisingly, most dairy tasks were split relatively evenly by gender. Further research could investigate the ways different production systems influence household division of labor: for example, since women generally take charge of more domestic tasks, in zero-grazing households is dairy-related labor more commonly performed by women?

- Both men and women perceived men to be more knowledgeable on all topics asked about (nutrition, hygiene, artificial insemination, and feed). One positive of digital advisory compared to traditional in-person systems is that both women and men are able to read the advice on their own, and thus may be less subjected to the influence (and doubts) of peers and other household members. However, this knowledge gap may have implications for marketing: if women are systematically viewed as less knowledgeable, men may find a service that aims to disrupt that balance in the household to be threatening. Additionally, the perceived knowledge gap may pose a barrier to adoption of recommendations by women if proposed without male buy-in and perceived to not know what they are talking about.

- The allocation of financial power in the household was far from clear-cut. A similar proportion of both genders received payment for and made decisions regarding milk money, and respondents of each gender disagreed as a group about which gender sold and received payment for crops. Additionally, the majority of respondents of both genders reported making financial decisions and being a “primary decision-maker” – either individually or jointly with a spouse or household head. Finally, both male and female respondents reported discussing finances with their spouse and trusting their spouse’s financial decisions. While this has positive implications for adoption of advice by both genders, it also suggests that many decisions are made jointly and buy-in from both spouses is necessary for implementation.

- The responses of respondents of both genders to the Likert scale questions suggest a high level of intra-household communication, trust, and cooperation, at least in the subjective opinions of respondents. Similarly, the vast majority of respondents of both genders contributed at least a medium amount (40 out of a possible 100 Ksh) to the common account in the public goods game. This has positive implications for adopting recommendations, which in many cases will require collective household buy-in. That said, there remains opportunity for a more granular understanding of intra-household cooperation. For example, how does it differ in households with more defined household and/or farming roles, or in households where one spouse is clearly knowledgeable? (While this dataset contains questions to this effect, the sample size is too small to draw meaningful conclusions about precise subsets of respondents.) Outside of this data, what impact do production systems (i.e. zero-grazing) and use of particular technologies (e.g. machinery such as chaff cutters or other equipment, such as durable water tanks) have on the level of intra-household cooperation?

While the effort to better understand our service users is ongoing and our efforts to improve content and delivery are constantly evolving, this data collection yielded meaningful insights and constituted a significant step towards inclusive product and service design that can be put to use in PxD’s Kenyan dairy service – and more broadly in programming across the region.

Since August 2020, PAD has collaborated with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), a UN affiliated multilateral agency, to deliver digital advisory to assist smallholder farmers in Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan to boost productivity and resiliency as they navigate the evolving impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 05 May 2021, IFAD convened an #IFADinnovationtalk webinar to showcase our partnership under the auspices of presentations and a panel discussion entitled ‘Digital Agriculture and the Rural Poor: Challenges and opportunities in delivering results’. Keynote speeches were delivered by Michael Kremer, PAD co-founder and Nobel Prize winner, and Owen Barder, PAD CEO. Our colleague Uzoamaka Ugochukwu, Nigeria Country Launch Manager, participated in a panel with Vivian Hoffman (a PAD research partner at IFPRI) and Dr. Zahoor-ul-Hassan (a key champion of our work in the Government of Punjab, Pakistan), and Patrick Habamenshi (country manager of IFAD Nigeria).

As Owen Barder, PAD’s CEO, stated in his keynote address, our collaboration with IFAD has demonstrated:

First, that our services can be replicated, adapted and scaled in new geographies, and can be scaled up to new target populations in existing geographies;

Second, that we have been able to develop and deploy surveys and A/B tests to quickly and accurately gather and analyze information from users to improve our services and adapt to evolving challenges in near real time; and

Third, the combined capabilities of governments, multilateral organizations and non-profit service delivery organizations can deploy services quickly and at scale, using local talent and shared knowledge and systems.

The full text of Michael Kremer’s contribution is accessible here; Owen Barder’s speech can be accessed here; and a full recording of their presentations, panel discussion and subsequent Q&A is accessible via the video posted at the top of this page.

We envisage this our partnership with IFAD as both a mechanism for recovery from the devastating effects that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on smallholder farmers, and an investment in better ways of delivering agricultural information in the long term.

We are excited at our progress in advancing our systems to complement IFAD’s work in support of poor rural farming families and look forward to further success as we continue to work together to service poor, rural families with valuable and productive information.

Owen Barder, CEO

Research Associate Sam Strimling argues that one must understand the specific needs of women to inform effective service delivery and presents an upcoming effort to gather these insights prior to launching a PAD advisory service aimed at Kenyan dairy farmers this summer. This post is the first of a two-part series, in which the subsequent installment will provide an analysis of the results for the survey described in this post. This is also the third in a series of blog posts on gender and digital development to mark International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month.

PAD empowers smallholder farmers across the developing world with actionable information to improve their wellbeing. However, there is evidence that digital advisory services like ours are underused by women. This summer we are expanding our agricultural advisory service in Kenya to the dairy sector, an arena in which women play a central role. As we prepare to launch, we are looking beyond one-size-fits-all solutions to more effectively address the unique needs, preferences, responsibilities, and constraints of female farmers.

This post is the first of two about a survey we are conducting in April 2021 to better understand gender roles and power dynamics in Kenyan dairy production and to better target our new service to the underserved needs of women in this sector. Here we describe the motivation and design of this survey. In a follow-up post, we will share insights from the results.

Invisible Women Farmers

In her spectacular book Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez details case after case in which service providers failed to deliver because they neglected to collect data about female users’ specific needs, preferences, and priorities.

The book cites the example of an organization seeking to provide “improved” seeds for staple crops: Male farmers cared more about increasing outputs. Women farmers, on the other hand, were more concerned with their input of time and labor in the field and in cooking the staple for household consumption. Since, adopting this new technology would require those doing the planting — women — to increase their time and effort, the seeds were not adopted.

Women often have less agency in agricultural and household financial decision-making. This is illustrated by Criado Perez who cites two failed attempts to introduce clean cookstoves capable of significantly reducing women’s exposure to toxic smoke. A model promoted in India required regular maintenance, which was considered men’s work. Since the new stoves improved women’s health, but didn’t directly affect men, stoves often fell into disrepair for want of maintenance. In Bangladesh, the fact that the clean cookstoves did not directly improve men’s outcomes, meant that they were not purchased at all, as men controlled household finances.

Understanding Context and Culture

Dairy is a sector of agricultural production in which tradition and gendered labor run deep. As we prepare to roll out our new advisory service, we commenced by focusing on a series of questions we need to answer to understand labor and decision-making dynamics in the sector, and within smallholder households more generally. These include:

- Who performs which tasks in the household, and within dairy farming specifically?

- Who holds the authority to make decisions?

- How systematically do users think about farming and what level of knowledge do they have about dairy farming? Does this differ by gender?

- Who controls household finances and for what types of purchases, and which accounts do they use?

- To what degree do women and men communicate about decisions and trust each other to make decisions in the interests of the household, even if one is the final arbiter of a particular decision?

The phone survey we designed to collect this information is due to be deployed in the field in early July, and will be asked to pairs of spouses. The goal is to obtain information to enable us to better target our services to both genders. By asking both men and women within the same household the same set of questions, we will be able to learn about typical responses for each gender, and we will also be able to note whether there are some questions for which we receive vastly different responses from a husband and wife within the same household.

Our survey will consist of six sections:

- Household Tasks and Time Use: This section will collect information about the gender(s) and age(s) of those performing various household tasks, including crop farming, livestock grazing, and water fetching. This section also attempts to account for household members’ time spent on other tasks, such as jobs outside the home and schoolwork. Information arising from this section will allow us to measure, for each time-use category, whether an activity is primarily performed by men, women, girls, or boys, or a combination thereof.

- Dairy Tasks: This section is similar to the Household Tasks and Time Use section, but focuses specifically on dairy farming, since the research team is most interested in using the results of this gender survey for informing the design and distribution of dairy advisory messages. This section will allow us to measure whether the following dairy tasks are primarily performed by men, women, girls, or boys: cleaning milking equipment, observing animals, giving cows water, feeding cows/calves, milking, milk transportation/sale, cleaning the housing unit (if zero-grazing or semi zero-grazing), sourcing/threshing fodder, spraying/dipping (for tick prevention), deworming, seeking veterinary treatment / artificial insemination (AI) services, identification (ear tagging), debudding/dehorning, hoof trimming, and grooming.

- Scenario-Based Questions: These are questions for which answers seek to understand respondents’ critical thinking abilities. An example of such a question would be: “Mrs Choge realized that to boost milk production beyond 7 litres a day, she needed to give her cow sufficient concentrates. For every 1.5 litres of milk above 7 litres, she gave 1 kg concentrate. How much concentrate should she give a cow producing 10 litres of milk per day?” We will disaggregate the results by gender to determine whether, on average, men or women think more systematically about dairy farming. This type of question tests the respondent’s causal reasoning, logical deduction, and systematic planning.

- Knowledge-Based Questions: This section is similar to the scenario-based section, but instead tests respondents on their technical dairy knowledge. As in that section, these questions have correct answers, and we will disaggregate the results by gender to determine whether, on average, men or women have more technical knowledge about dairy farming.

- Financial Decisions: This section will allow us to draw conclusions about who within the household holds financial power, with regards to purchases of productive assets, personal assets, and consumption goods. We will measure this empirically by collecting information, disaggregated by gender, on transaction amount as well as account type (digital/cash, joint/solo).

- Public Goods Game: In this section, respondents will be asked whether they want to augment the amount earned for participating in the survey by allocating a portion to a common account with their partner. A random amount will also be added to the survey by the research team, such that it is not possible for the respondent to lose money by completing this exercise, only to increase their earnings by a variable amount depending on the contribution made by both members of the spousal pair.1 This section allows us to collect data on trust within each spousal pair, which we assume to be correlated with the total amount contributed into the common account.

We plan to publish our findings to inform our own platform development and to make them available to other service providers and policy makers concerned with smart service design. In doing so, we plan to add to the existing body of research on gender and international development — a more complete review of which was published by my colleague Theresa Solenski in an earlier blog post.

Surveying the Evidence

Specifically, our research will add to the empirical evidence base on asymmetric information within the household. One study in Ghana found that on average, both men and women commonly underestimate or overestimate their spouse’s expenditures by more than 75%. Concerningly, this research found implications for profitability: the more imperfect the husband’s information about his wife’s expenditure, the lower the wife’s output/profit, and vice versa (Chen & Collins, 2014).

Another study from Uttar Pradesh provided an example in which women were less likely to adopt productivity-enhancing technology (in this case, laser land-leveling because they were less aware of its impact (Magnan et al. 2015)). Similarly, a study from Uganda in which agricultural videos were shown either jointly to a spousal pair, or separately to one member, found that information was not shared within the household when just one member was engaged (Lecoutere et al. 2019). These examples are particularly relevant to our work at PAD, as they highlight a way in which our service has the potential to fail: if our messages primarily reach men but women are charged with implementing the recommendations we provide (or vice versa), the suggested practices may not be adopted because we failed to get the information into the hands of women who can make it actionable.

Our survey will contribute to the literature on within-household asymmetric information in two ways. First, the sections on household tasks / time-use, dairy tasks, and finances will — in addition to providing information about gender roles — enable us to compare directly the wife’s knowledge of household affairs to that of her husband (and vice versa). Second, the sections quizzing respondents on dairy knowledge and testing of systematic thinking through scenario-based questions will measure within-household information asymmetries with respect to dairy farming.

Imperfect communication and limited trust also have implications for message adoption: Qualitative evidence from a focus group discussion with 113 male farmers and 141 female farmers in Malawi suggests that men often do not trust agricultural information received from their wives, and female farmers may be hesitant to suggest new agricultural practices for fear of retribution (Ragasa et. al., 2019). Another group of researchers partnered with Kakira Sugar Ltd., a large sugar company in Uganda that sources sugarcane through contracts with smallholder farmers, the vast majority of whom are men. This study implemented an intervention in which men were encouraged to transfer uncontracted blocks of sugarcane to their wives. Since both spouses needed to agree to the proposed intervention, whether the men were willing to do so provided in and of itself a measurement of trust. The researchers found a man was less willing to transfer the contract — i.e. was less trusting of his wife’s capabilities in this respect — if the household had fewer assets and/or expenditures, if his wife was not already involved in sugarcane farming, or if he had previously expressed a preference for managing the household’s finances himself (Ambler et al., 2021).