2022 was a tremendous leap forward for research at PxD. Our research and operations teams completed a total of eight A/B test experiments and impact evaluations. We collected data in person and over the phone from approximately 20,000 survey respondents in 27 distinct surveys that took place in Kenya, Ethiopia, Colombia, Pakistan, and three states in India.

We generated new insights to build future programming such as an SMS agro-dealer directory to reduce input market information frictions, built evidence-based proofs of concepts for innovative service design such as WhatsApp-based crowdsourcing chatbot and learned to leverage research partnerships for scalability with dairy cooperatives. We used research insights to shift and refine our approach and we are excited about further impact evidence from forthcoming analysis in 2023.

Devastating events in 2022 from drought in the Horn of Africa to the 100-year flood in Pakistan emphasize that climate change is one of the most urgent challenges facing our users. As such, we have intensified our research efforts to identify interventions that can improve smallholder livelihoods whilst incorporating climate adaptation and mitigation efforts into our existing services. We’ll continue this innovation research agenda in the coming year to explore high-value innovations to supplement our core digital agricultural advisory.

New insights to build future programming

Across a diverse portfolio of research projects, we have demonstrated the value of PxD’s services and contributed to an expanded knowledge base on digital agricultural extension. A particularly promising finding is establishing that digital tools can be effective in improving in-person extension services.

Performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages could increase extension volunteers’ performance: Through a large-scale randomized evaluation in Rwanda, we demonstrated that performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages – particularly goals that were ambitious but attainable – could improve community extension volunteers’ (known as Farmer Promoters – FPs) performance and therefore generate positive impacts on farmers’ outcomes. Sending goal reminders to FPs significantly increased the number of farmers trained by 3.1 percent, led to a significant 4.3 percent more training sessions being delivered, and increased farmers’ registration for subsidized inputs by 1.9 percent (statistically insignificant) over FPs who did not receive goal reminders. Given that the unit cost for each SMS is $0.006 and the average number of farmers assigned to each of the ~14,000 FPs across Rwanda is 190, the effect sizes of these messages are likely to be highly cost-effective.

The results of the Rwanda project support the expansion and replication of extension agent interventions in other settings targeting different populations in the future. In addition, these results point to areas for future research and development that could enhance the effectiveness of extension agent services. For example, we are interested in exploring how digital tools can be used to help extension agents set performance-increasing goals, direct them to farmers most in need, and extend information access to farmer populations that may not benefit from direct digital advisory services.

A digital directory of agro-dealers has the potential to increase the adoption of recommended inputs: In Kenya, we found evidence that farmers can benefit from the provision of an SMS agro-dealer directory by reducing input market information frictions. Our preliminary empirical findings suggest that – particularly for a directory that includes stock and price information about agro-dealers – access to this tool prompts farmers to refine their choice of agro-dealers before an in-person visit. Farmers in the treatment arm who had access to the agro-dealer directory and stock information contacted 21 percent more agro-dealers, but visited 4 percent fewer agro-dealers relative to the control group which did not have access to the tool. This suggests that farmers in this treatment arm used the contact information to call more agro-dealers before spending time and money to travel to the shops themselves.

Farmers given access to the agro-dealer directory were more likely to purchase PxD-recommended inputs and experienced fewer stockouts than those who didn’t have access to the directory. When pooling the two treatment arms, we observe that consistent with PxD’s advisory recommendations, treated farmers were 6 percent more likely than control farmers to use hermetic bags to store maize – a practice shown in rigorous studies like Ndegwa et al. (2016) to prevent post-harvest losses from pests. Farmers in the treatment arm with access to the directory but not stock info appeared to contact and visit agro-dealers at the same rate as the control group but then were 22 percent less likely than the control group to report facing an input shortage when they shopped (meaning they were more likely to find and purchase the product they were looking for).

Building on these promising findings, we hope to identify opportunities to further develop a scalable digital agro-dealer directory tool. Specifically, we are interested in exploring ways to onboard a large number of agro-dealers and update the stock information at a low cost.

Building proofs of concepts

Digital peer groups increase farmer interactions and potentially increase the adoption of recommended practices, but we need creative ways to form groups at a low cost: Various research projects aimed to demonstrate proof of concept for novel interventions that PxD was exploring for the first time. For example, we now have empirical evidence that an intervention in Kenya to organize farmers into groups and send them SMS nudges to communicate with each other was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members. Treatment farmers who were organized into digital peer groups had higher interaction levels than their control group counterparts and were 43 percent more likely to meet with their group members on a farm than control farmers. Interacting with one’s group members on a farm was also associated with increased adoption and knowledge of recommended practices.

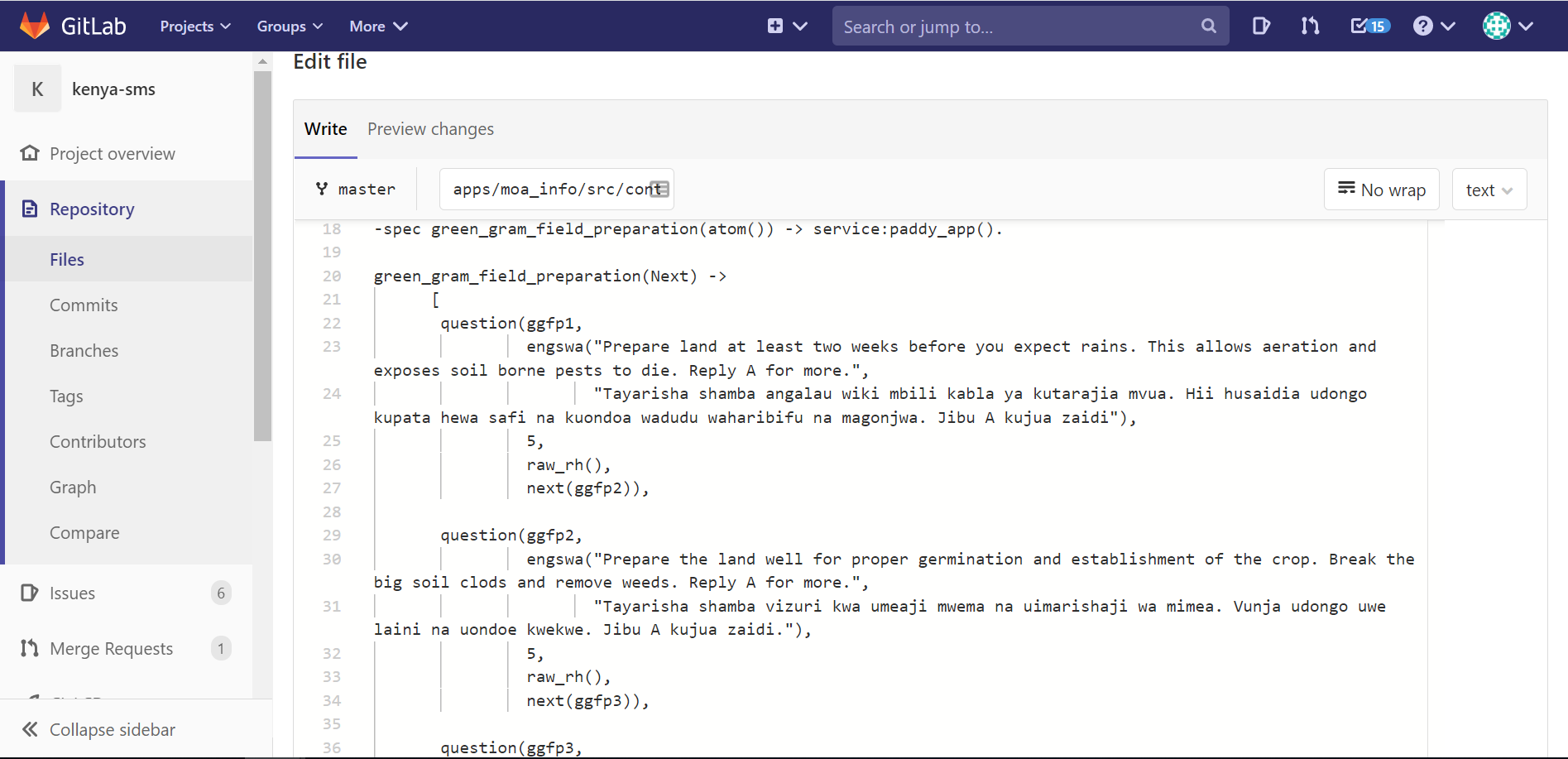

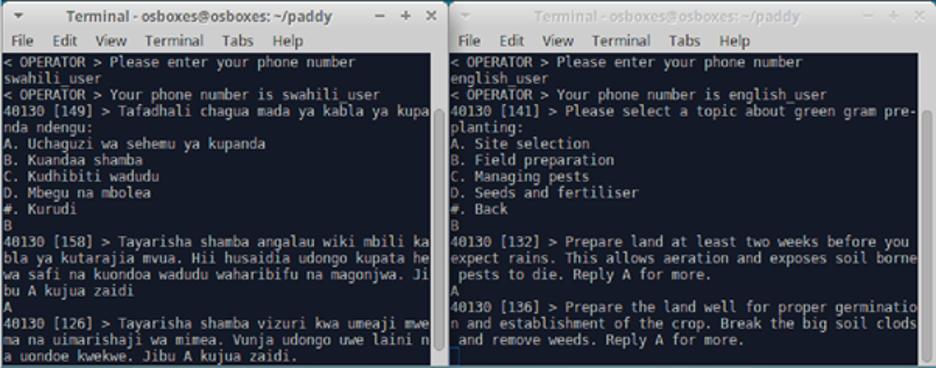

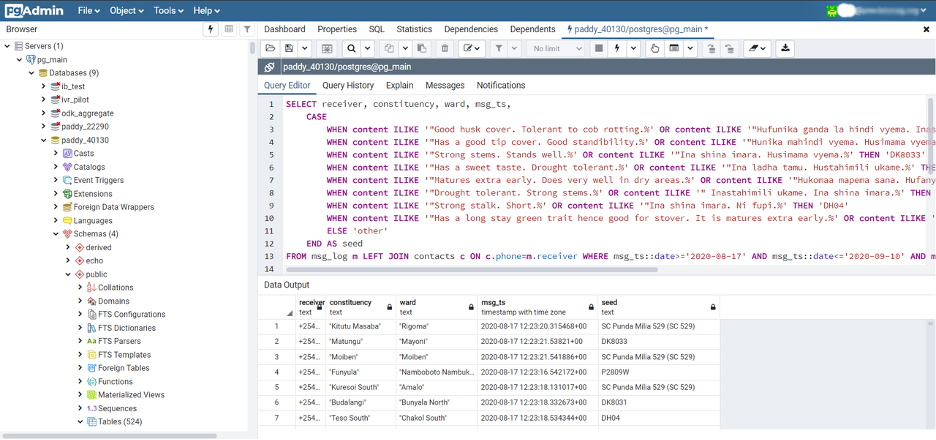

A gig-worker model for crowdsourcing agricultural field photos has the potential to generate real-time data on field conditions: We acquired institutional knowledge, both technical and regulatory, to build and operationalize crowdsourcing platforms to demonstrate the feasibility of crowdsourcing information from agro-dealers and farmers in Gujarat. In a pilot, we set up a WhatsApp chatbot, integrating a WhatsApp Business Account with our in-house user communications platform, Paddy, to guide users through a systematic inspection of a field for crop health issues and send reports back to PxD with their findings.

Eighteen of our recruited farmer agents consistently engaged with the program over 10 weeks, with a median of nine crop health reports per agent. The quality of field reports was high – approximately 94 percent of reports are usable. In total, we received 220 field reports with accurate GPS locations and usable photographs. Each of these reports costs INR 125 (USD 1.67), which is substantially below the cost of a 15-minute phone survey. This suggests that crowdsourced data could be a cost-effective method of collecting local data.

PxD aims to further build this knowledge to crowdsource various types of information and use it to improve future service offerings by customizing advisory to be more locally relevant and actionable.

Working with smallholder farmers in the fight against climate change

We are intensifying our efforts to provide information to smallholder farmers that will allow them to make informed decisions to reduce the risks that climate change presents to their livelihoods and to consider adopting practices that can actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We approach this work with the guiding principle of farmer welfare first: smallholder farmers cannot be expected to pay the price for climate change mitigation. Climate change-related advisory should directly support livelihood gains via improved agricultural output or renumeration .

PxD, in collaboration with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD), worked to assess opportunities to benefit poor farming communities through their participation in climate mitigation activities and to direct tangible returns to participating smallholder communities.

The PxD-IGSD collaboration has focused on exploring four mitigation areas with most promise in agriculture: Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced rock weathering; Carbon dioxide sequestration with organic carbon storage in soils and plant biomass; Nitrous oxide mitigation through precision nutrient management; and Methane mitigation in dairy through improved livestock feeding practices.

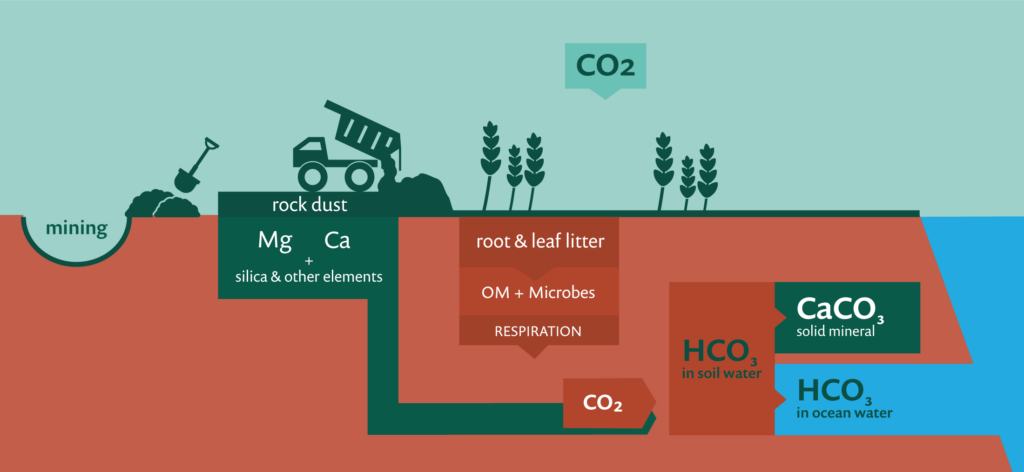

- Enhanced rock weathering (ERW), an emerging technology that permanently draws down carbon from the atmosphere and has the potential for agricultural co-benefits makes it an attractive mitigation strategy in the smallholder farmer context.

- There is evidence that conservation agriculture practices that many farmers are already familiar with – such as reduced tillage, the use of cover crops, and intercropping – promote the sequestration of organic carbon in soils.

- In terms of nitrous oxide emissions, simple decision support tools following the Site Specific Nutrient Management approach, i.e. Leaf Color Charts (LCC), have been shown to reduce nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use as well as improve farmer outcomes.

- For methane, improving feeding practices that increase milk production and closing the dairy yield gap in the Global South per cow can lower the methane intensity of production and contribute to methane mitigation, as well as improving farmer livelihoods.

We’re excited to be on the cutting edge of exploring the potential of these climate change mitigation opportunities- like scoping a digital version of Leaf Color Charts to enable the tool to reach a wider scale and Advanced Market Commitments to incentivize R&D for enhanced rock weathering. Our research initiative with IGSD has enabled PxD to identify future activities within each opportunity area to advance climate change mitigation in the smallholder farmer context and we are actively pursuing partnership and funding opportunities to advance these activities.

Learning to leverage research partnerships for scalability

Partnerships have proven to be a critical pathway to increasing impact and scaling evidence-based programs across our project portfolio.

By collaboratively identifying and developing high-impact opportunities with dairy cooperatives in Kenya, PxD has identified a new partnership model in which PxD serves as a technical and analytical partner for innovating and testing service offerings for cooperatives, and builds cooperatives’ capabilities for generating greater impact at scale. We kicked off the partnerships with Lessos Dairy and Sirikwa Dairy by adapting an asset-collateralized loan product for water tanks which has been shown to dramatically increase access to water tanks among dairy farmers in a research study (Jack et al, 2022) and setting up an evaluation to measure its impact on economic and household outcomes.

In Gujarat, India we surmise that identifying low-cost and scalable approaches to crowdsource pest information will require leveraging local organizations and existing social networks for cost-efficient recruitment and training of agents.

To further explore opportunities to support women farmers in Gujarat, we successfully established partnerships that allow us to better understand the constraints women farmers face in engaging in economic activities and their access to information and other services. These partnerships allow us to design and implement group-based digital services to address those specific constraints.

Insights to shift and refine our approach

Our scoping activities allowed us to identify when a change in approach was needed or when interventions did not turn out to be as promising as we had hoped.

In the dairy sector in Kenya, we learned that existing market and coordination failures, such as credit constraints, need to be addressed to create an environment in which digital advisory can effectively improve smallholder dairy productivity.

In testing social learning mechanisms in Kenya, we did not find evidence that the designed intervention increased farmers’ knowledge or the likelihood of adopting recommended practices, despite finding that peer learning was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members.

While subsequent qualitative interviews suggest that some farmers visited the farm fields of their peers and experimented with the recommended practices in a small portion of their plot, developing the digital peer group advisory further is likely to require a substantial investment in basic research to understand farmers’ social learning process and identify creative ways to reduce the relatively high costs associated with forming peer groups.

Finally, we learned to exercise caution in working with established women’s groups in Gujarat in a way that does not exacerbate local power dynamics within communities to ensure PxD’s services are designed in a sensitive way to promote the inclusion of marginalized groups that may face particularly challenging digital access gaps.

Looking forward to continue building our evidence base

In the coming year we are looking forward to continuing to build our evidence base with forthcoming insights on PxD’s impact on farmer welfare from several large-scale RCTs in India, Uganda, and Kenya.

For the impact evaluation of our largest service offered to date for rice farmers in India, endline data collection and analysis are expected following the second season of implementation in 2023. In addition to outcome data on farmers yields and profits, we’re excited to generate additional insights on scalable measurement options for detecting yield changes among rice farmers using remote sensing data.

In Uganda, our work with coffee farmers enabled PxD to explore several dimensions of digital advisory, including comparing a stand-alone digital advisory service to the provision of digital advisory as a complement to in-person training and studying social spillovers from our advisory services. An endline analysis of the effects of this program will be forthcoming in 2023.

We are also excited to generate initial insights on the impact of asset-collateralized loans for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. Using frequent administrative data from dairy cooperatives on milk production, we’ll be able to understand how improved access to water tanks helps farmers mitigate productivity shocks and domestic water shortages as farmers adapt to more dry spells from a changing climate.

In addition to evaluation research with rigorous RCTs, we look forward to building out our research innovation agenda in the coming year. We are exploring a variety of new, evidence-based high-value product innovations that can build on our agricultural impact for smallholder farmers, such as interventions to facilitate market linkages and access complementary financial services. We are committed to using rigorous evidence and deep user research to identify and prioritize which ideas to pursue.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2023! If you’d like to learn more or partner with PxD on specific areas highlighted please get in touch!

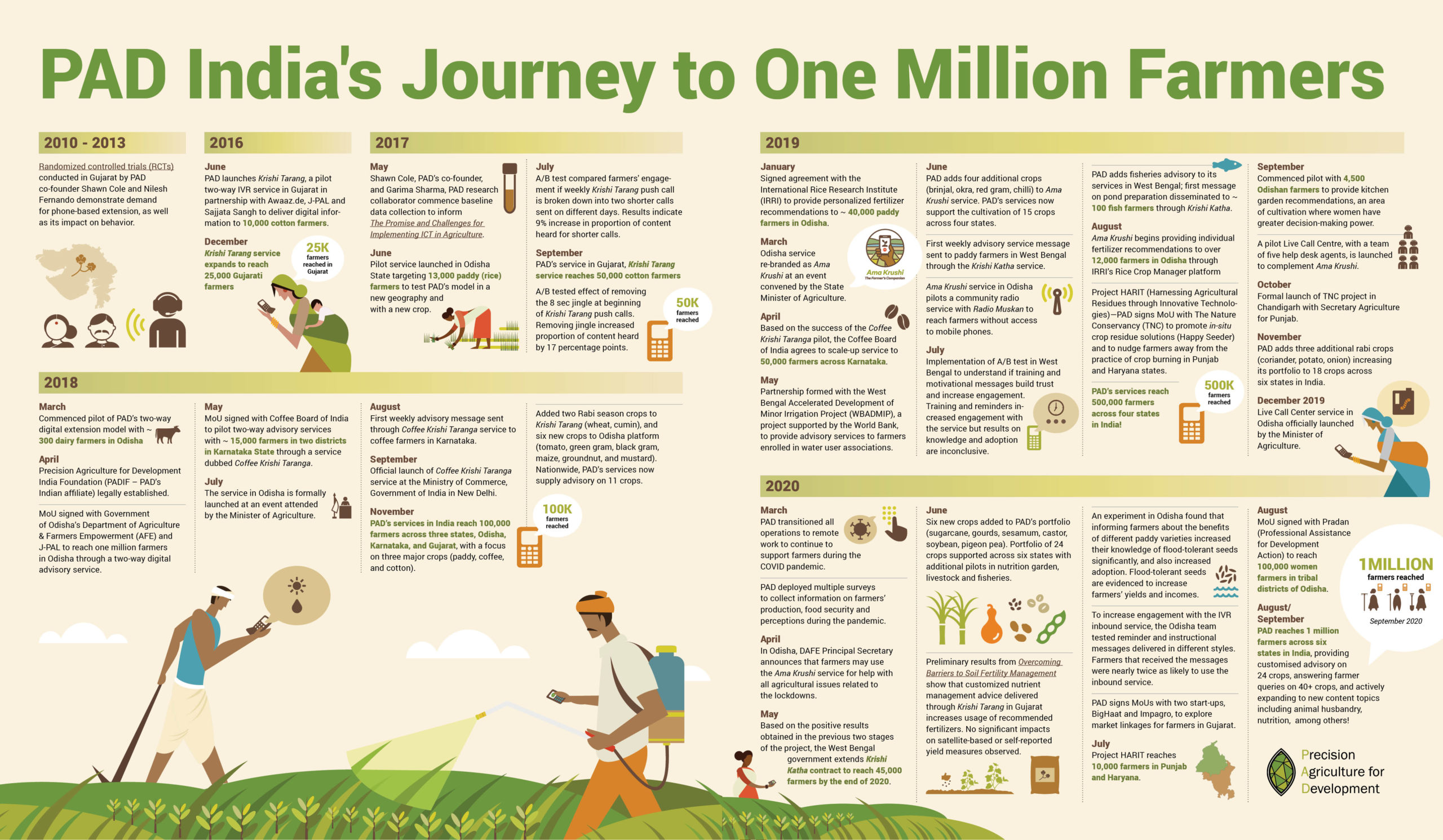

On 1 August 2022, PxD completed the transition of the management and operations of Ama Krushi – our largest digital service – to Tatwa Technologies Limited, a third-party firm that won a competitive government tender. This post reflects on Ama Krushi’s journey from concept to a fully-fledged digital advisory service providing customized agronomic advice to over three million farmers, and recounts some of the hard truths, lessons learned, and innovations uncovered.

The successful handover of Ama Krushi to Tatwa is bittersweet, marking the culmination of years of work to build a sophisticated digital extension service from scratch. But the transition also means the end of a remarkable journey and a farewell not only to a service we are justly proud of, but also to longstanding colleagues who have transitioned with the service to new management.

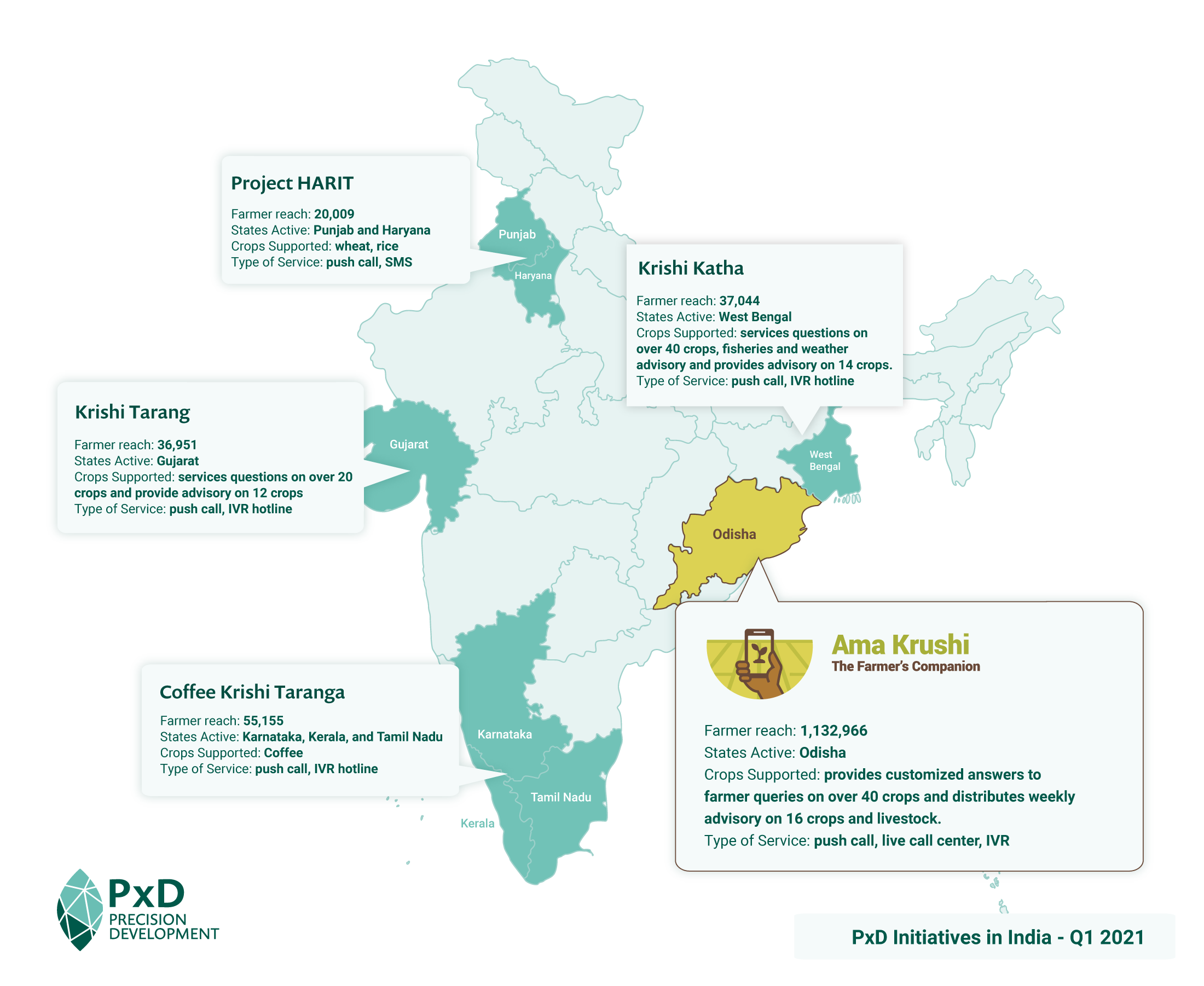

In 2018, PxD (then Precision Agriculture for Development) – in partnership with the Department of Agriculture and Farmer Empowerment (DAFE), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), and the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) – launched “Ama Krushi” (“farmers’ friend” in Odia, the most commonly spoken language in Odisha State). Ama Krushi was envisioned as a digital farmer-advisory platform to deliver timely, customized digital advice free of charge to smallholder farmers in the state of Odisha via their mobile phones. Conceived as a build, operate, and transfer (BOT) project, its design envisaged the transition of the management of Ama Krushi to the government of Odisha at the conclusion of the implementation and scaling period. The partners imposed an ambitious target for Ama Krushi: by March 2021, the service would have leveraged research and evidence to build and scale a cost-efficient, statewide digital extension service to serve one million farmers.

As is often the case with well-laid plans, PxD’s journey was very different from what was envisioned in 2018. The initial transition timeline to transfer day-to-day management of the service in 2021 was revised as the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt.

The formal transition ultimately commenced on 1 April 2022 with the initiation of an intensive capacity-building and transfer plan. Tatwa began operating Ama Krushi independent of PxD on 1 June, with continued technical support from PxD staff. Tatwa assumed full responsibility – with PxD becoming entirely hands off – on 1 August. At transfer, Ama Krushi was actively servicing over 3.1 million farmers.

The early days

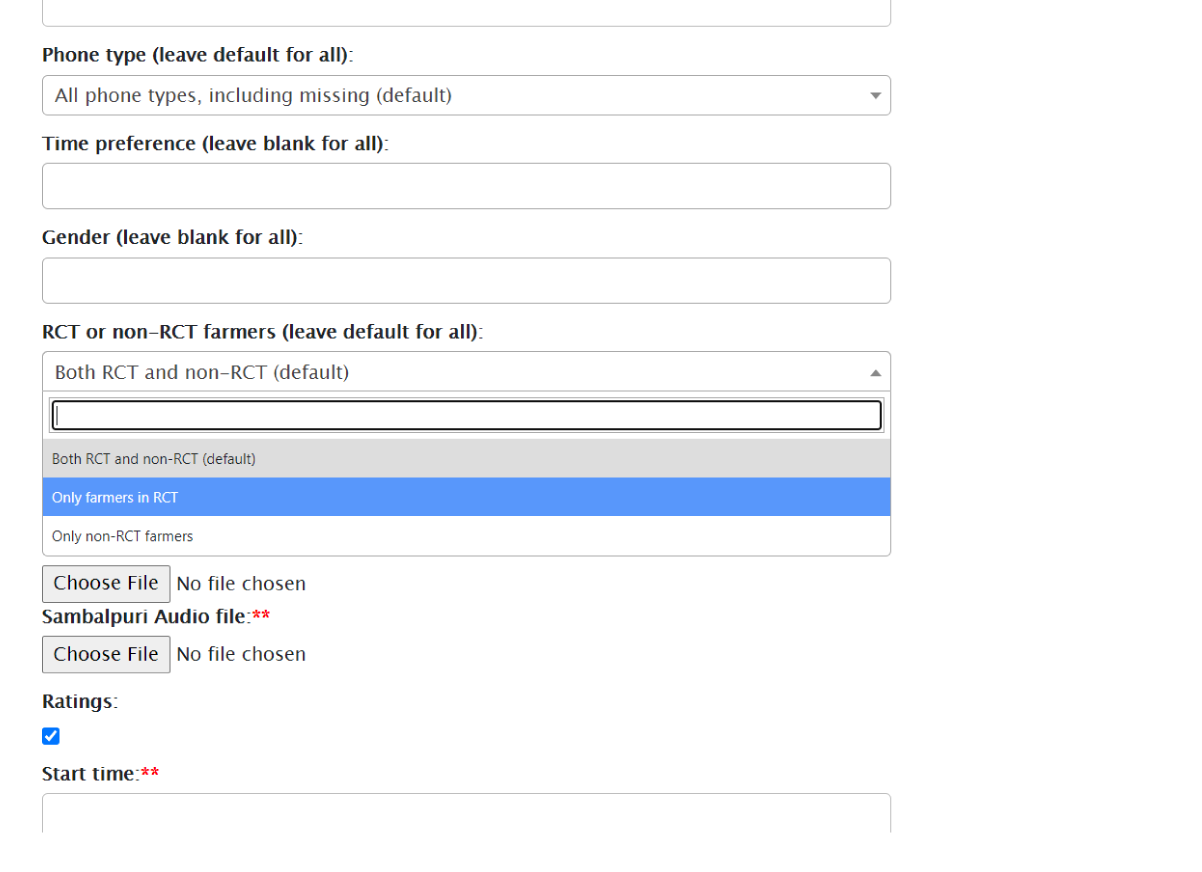

During the first two years of project implementation, Ama Krushi grew to provide advisory and information for 16 crops across all 30 districts of the state of Odisha. After consenting to be registered, each farmer added to the service was profiled by enumerators. In profiling, a cropping profile for each farmer was created and was populated by our call center team or by our field team on the ground. An accurate profile enabled the service to direct customized content to each farmer, timed to align with critical decision points on the agricultural calendar.

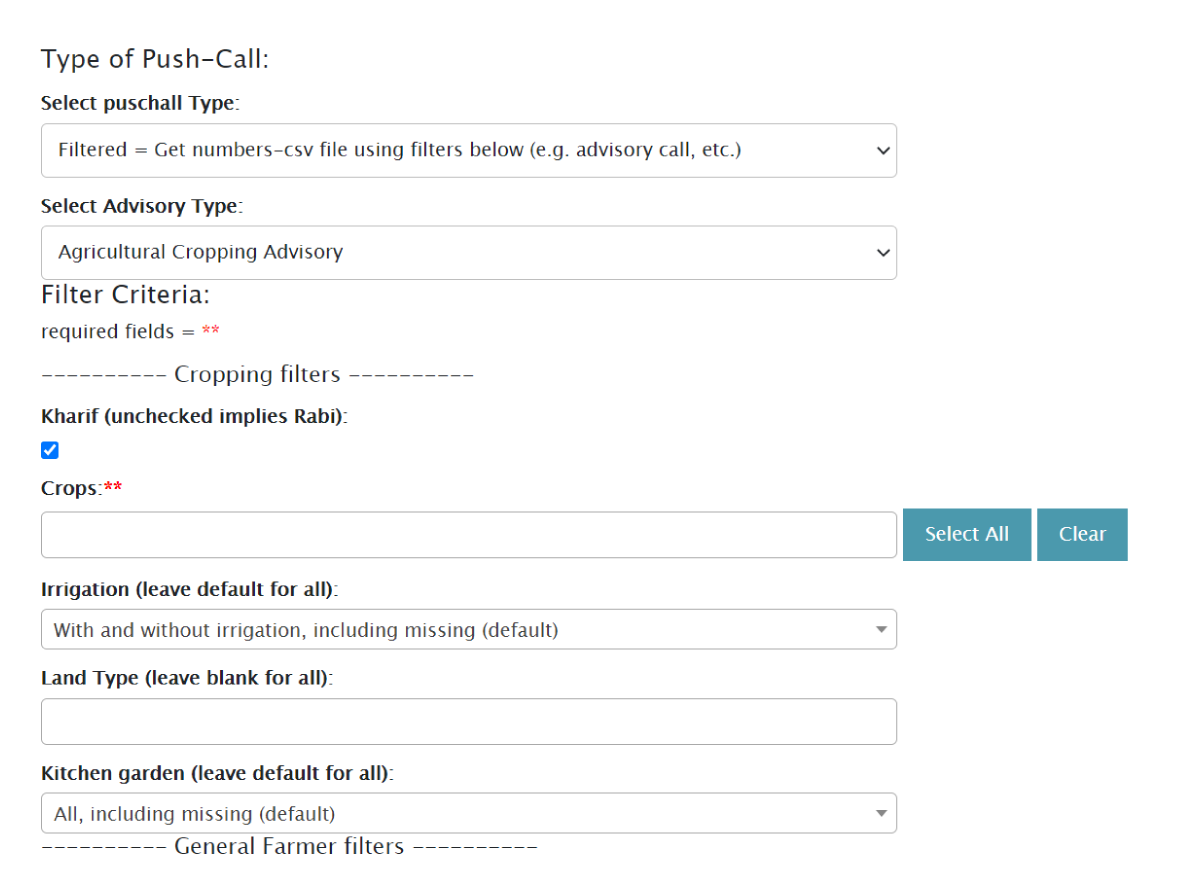

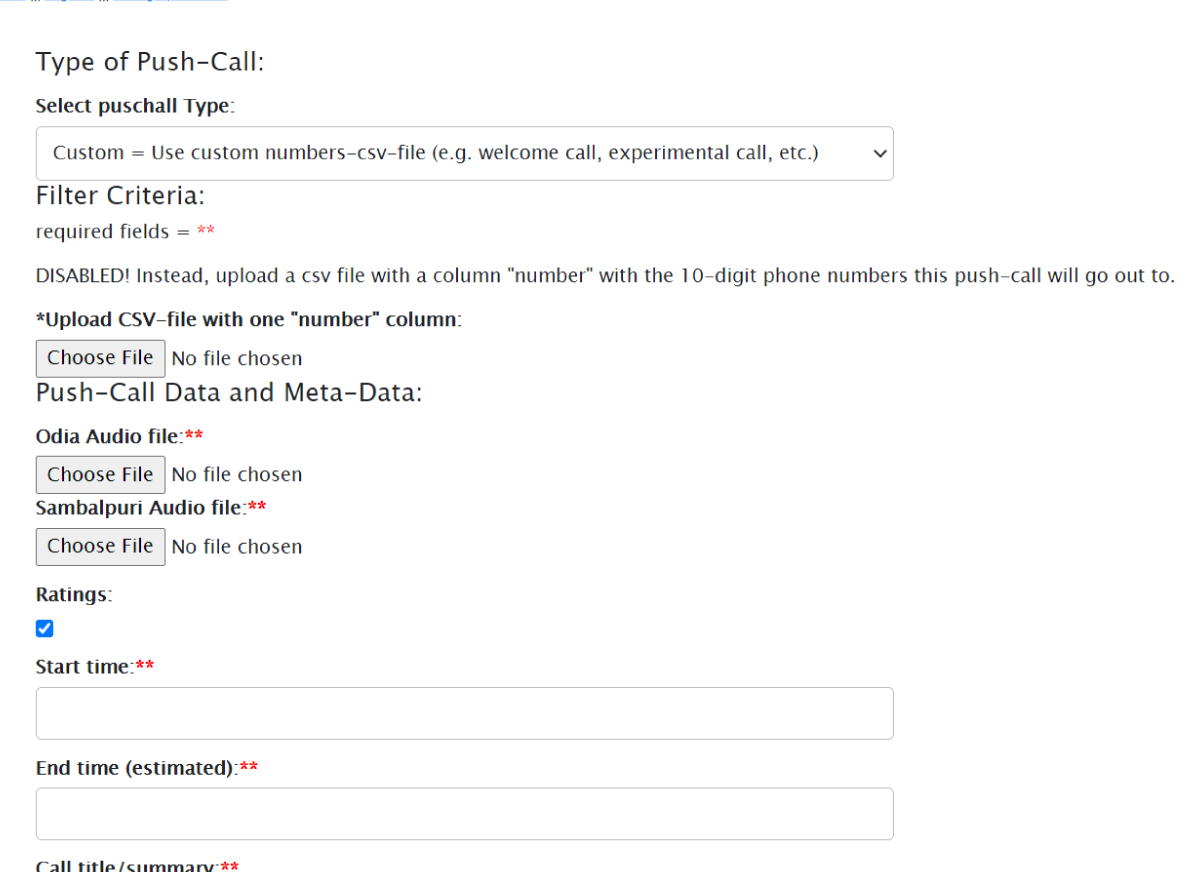

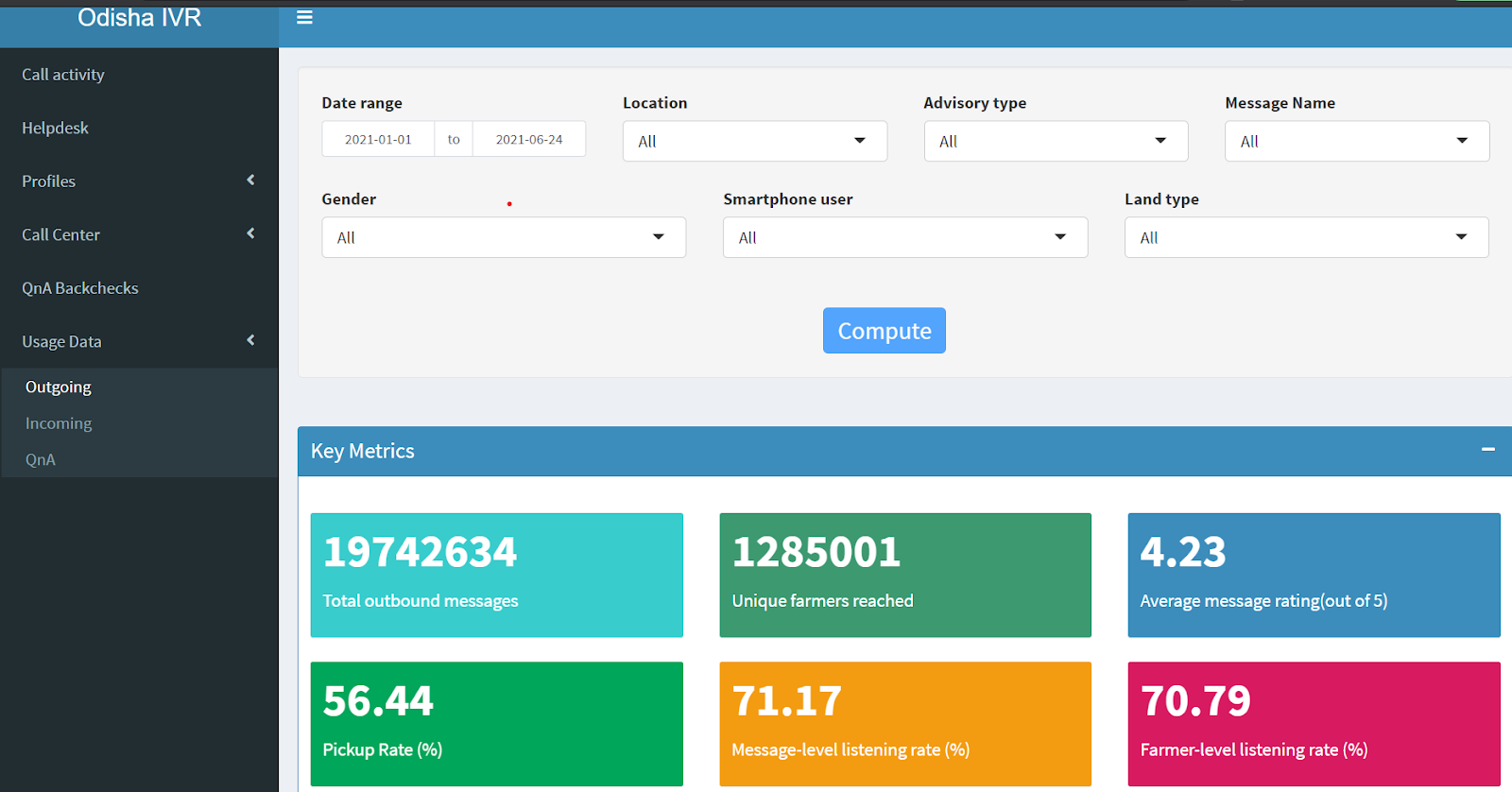

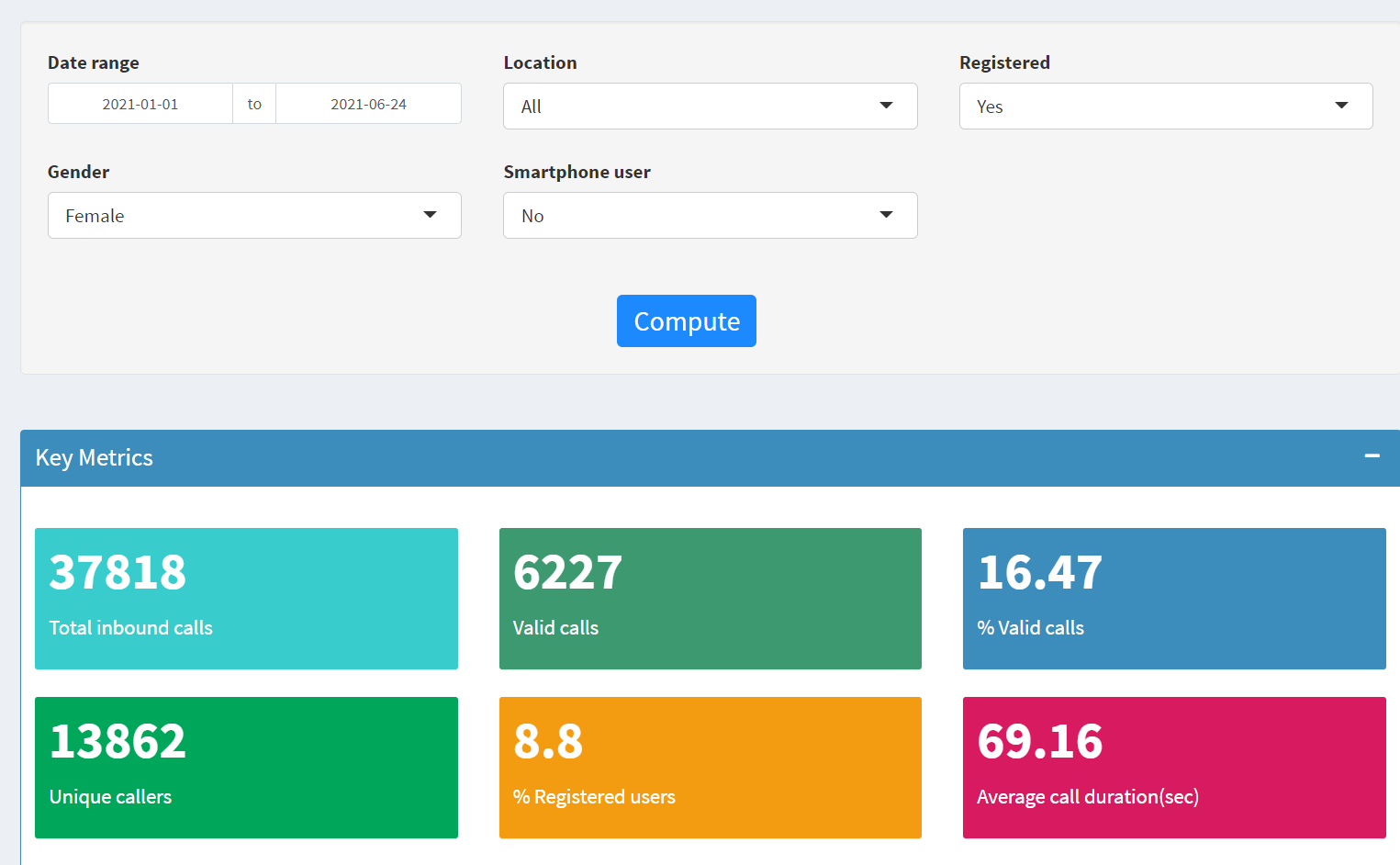

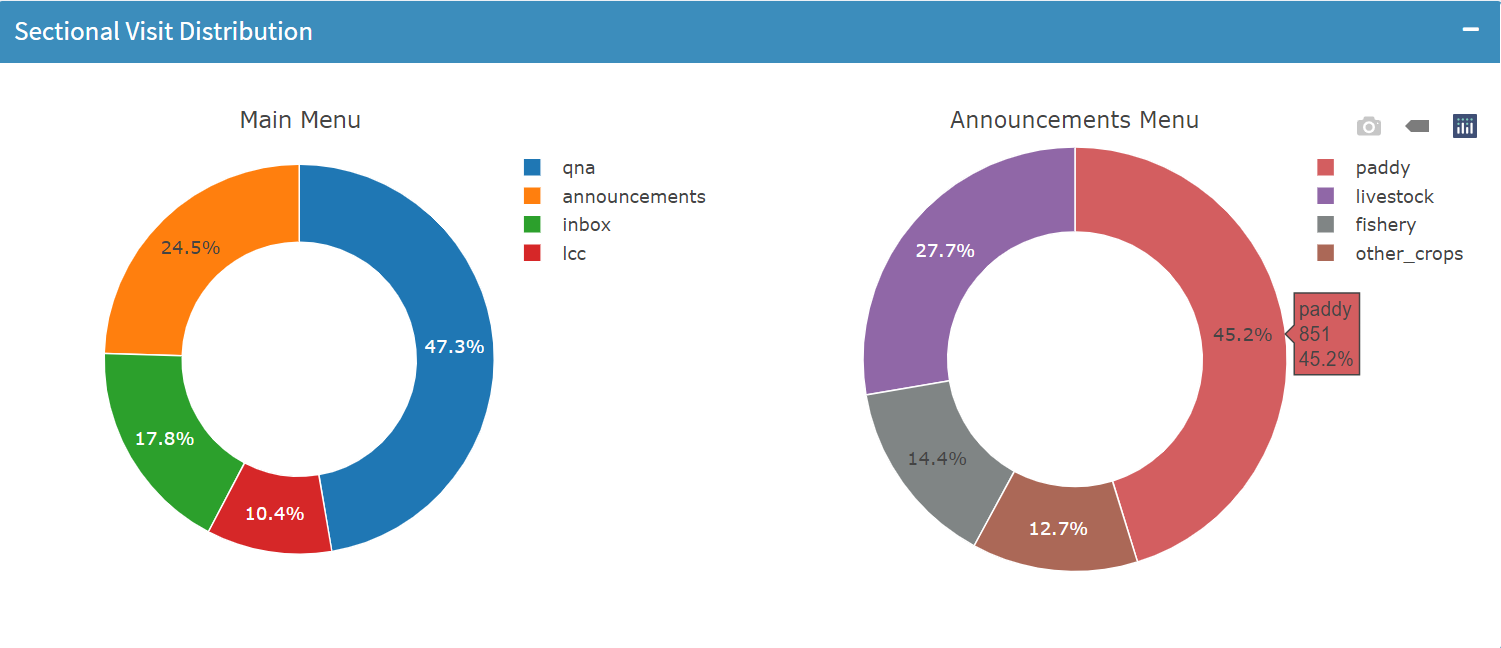

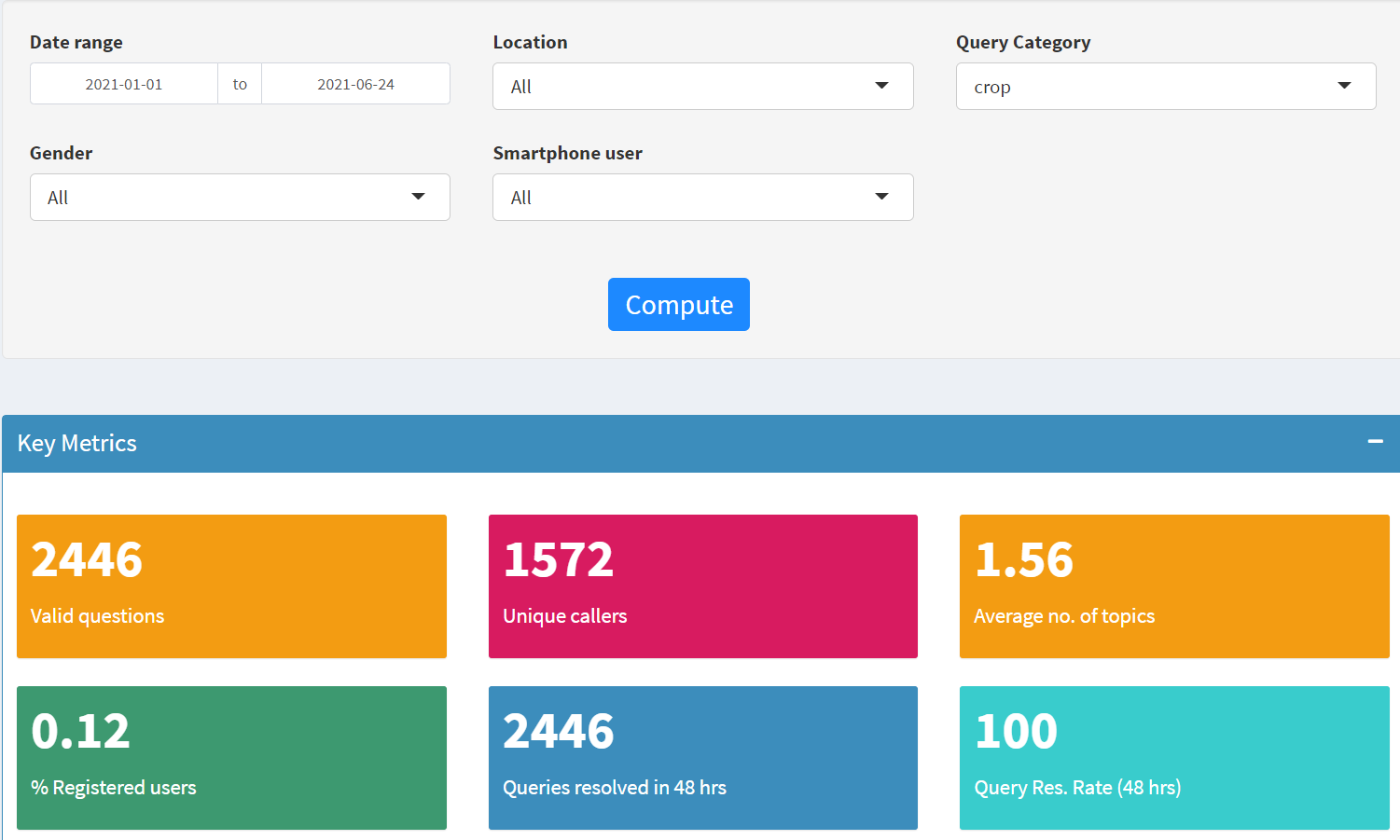

In the early years, the team focused on building out Ama Krishi’s core service: an interactive voice response (IVR) push call service that delivered weekly advisory information tailored to each farmer’s profile information, and a complementary farmer hotline. By placing a missed call to the hotline, farmers received a free return call, enabling them to access a library of advisory information and frequently asked questions, and the option to leave messages to be serviced by agronomists via a recorded push call within 48 hours (typically fulfilled within 24). While any farmer could ask a question, only profiled farmers received weekly advisory.

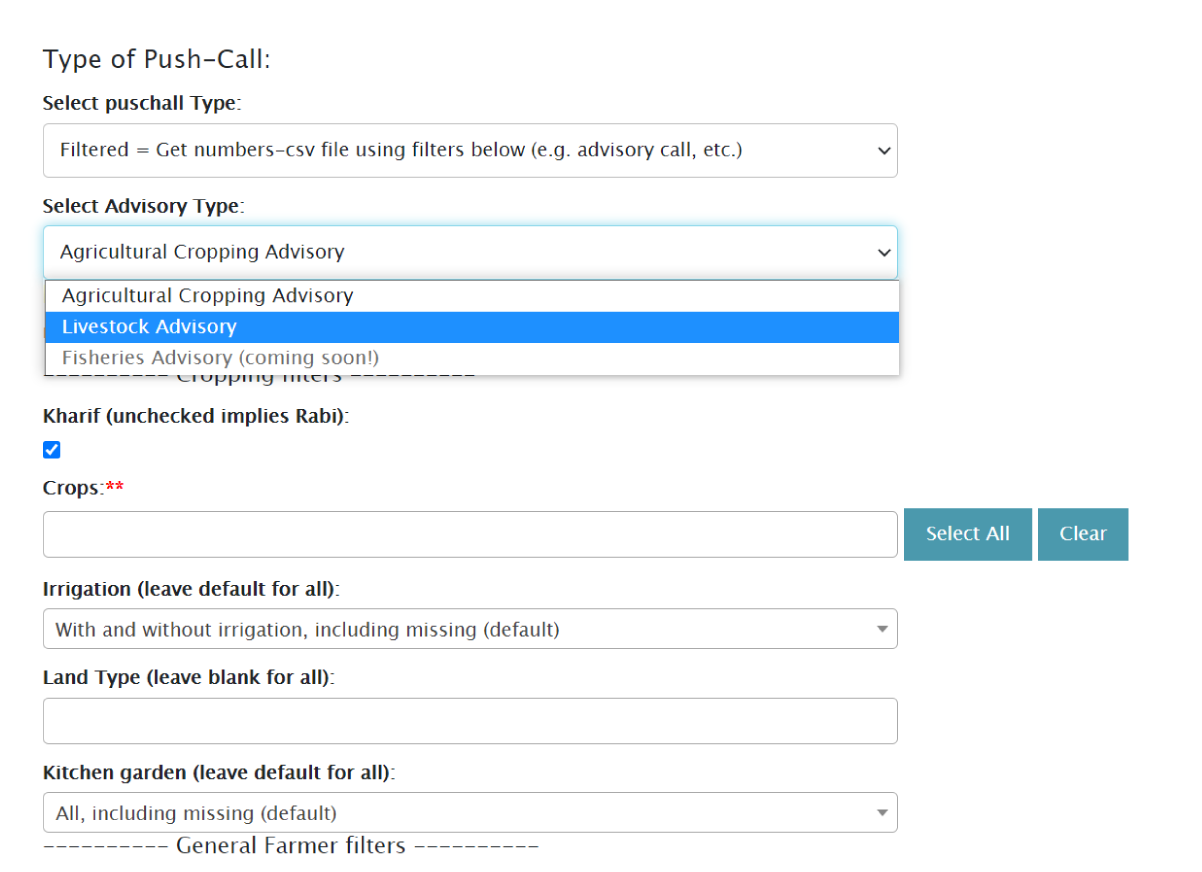

By analyzing trends in engagement and directly interacting with users during field visits and focus groups, we gather information to inform new products and service innovations that are relevant to the needs of users. Two prominent examples include the integration of Kitchen Garden Advisory, aimed at women who engage in subsistence farming, with our regular programming, and the expansion of our advisory to include non-crop-related value chains, specifically livestock and fisheries. During the first two years of operation, the Ama Krushi team explored different avenues for expansion while deploying A/B tests to iteratively improve modes of information delivery. At the end of 2019, Ama Krushi was serving over 620,000 farmers.

Similarly, in response to demand from farmers and our partners at DAFE, PxD added new digital channels to expand our reach to smallholder farmers. Radio remains an important medium for information dissemination in rural India. Accordingly, PxD piloted advisory dissemination via a local community radio station in early 2019. By September 2020, the pilot had evolved into a formal collaboration with the Community Radio Association of Odisha, with Ama Krushi broadcasting weekly advisory across 12 community radio stations. Community radio enabled us to reach many more farmers who were not registered on the service and advise them on how to register to receive the full suite of AK digital services.

We also added a live call center (LCC) in December 2019 so that farmers could call in to be connected to a live agent. Given farmers’ limited digital literacy, we observed that many farmers had trouble navigating the inbound hotline. To make the service more accessible, DAFE requested that we build out an LCC to help reduce the technological burden on farmers. Propelled by the government of Odisha’s request to have all services offered by Ama Krushi available under one short code, the LCC was added to the main menu in February 2021 – now, should the farmer wish to, they can call 155 333 and choose whether or not to engage with a live agent to have their concerns addressed. This is supplemented by an escalation system that ensures that the farmer receives the answer on the spot or through a push call within 48 hours.

In early 2019, PxD also ramped up the training and onboarding of extension workers and other village-level champions, which allowed us to grow the number of agents that could sensitize farmers on the Ama Krushi service. It also meant that content could be disseminated via a hybrid model to these groups (e.g. IVR and district-level WhatsApp groups).

Scaling through the pandemic

At the start of 2020, in consultation with our colleagues at DAFE and BMGF, we formulated a transition plan to transfer day-to-day management of the service to a third party in 2021, as per the initial BOT agreement.

No sooner had the execution of the transition begun, however, than our plans were upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, which presented challenges that we (and most organizations across the world) did not have the experience or knowledge to contend with. We reconfigured our operations to continue offering the service while adapting our operations to work-from-home.

The move to a fully remote, work-from-home operation underscored a cornerstone advantage of digital extension services: the ability to operate at times and places that traditional extension services cannot reach. In the first month after the pandemic, we transitioned our hundred-strong call center team to work-from-home arrangements, established a system to service agriculture-related distress calls (for example, being stopped by police when taking perishable crops to market after the issuance of a statewide authorization communique) and questions from farmers during the nationwide lockdown, and assisted the government of Odisha to deliver key agriculture-related updates to remote areas. The Ama Krushi team demonstrated remarkable resilience, maintaining and then building their capacity to serve farmers. The Ama Krushi service was available every day of the nationwide lockdown and subsequent phases of physical-distancing protocols, .

Despite significant operational adjustments imposed by the pandemic, Ama Krushi surpassed its target of servicing one million farmers in November 2020, five months ahead of DAFE’s initial target. Bolstered by Ama Krushi’s success, the government of Odisha issued a directive defining new targets and goals in March 2021. With additional support from BMGF, we received approval to launch advisory channels to support livestock and fisheries on the Ama Krushi platform. The government of Odisha also revised the end goal of onboarding 1 million farmers by March 2021 to 2.5 million farmers by June 2021.

While these requests reflected the Odisha government’s faith in Ama Krushi and our team, the revised targets and deadlines presented challenges for the handover of the service. COVID-19-related concessions had allowed for the extension of the original transition timeline from March 2021 to September 2021, but the addition of livestock and fisheries went beyond the scope of the original agreement and required us to test, launch, stabilize, and hand over a new version of the service within six months.

Undeterred, the Ama Krushi team quickly commenced piloting and testing to support the development of livestock and fisheries advisory, launching the two new advisory channels in January and April 2021, respectively. Concurrently, we continued to leverage research and user feedback to improve the service and began preparing operations and management materials in preparation for the handover.

Collating and organizing information about the service and the platform operations was an extensive exercise that required the creation of a large vault of documents. These documents detailed how the service worked (even as the service continued to change), outlined a framework to facilitate capacity building to support the transition of workstream ownership from PxDs’ team to government officers, and created a learning agenda to document and monitor the transition and inform future efforts.

Transition

Coordinating with the government during the pandemic was challenging – understandably, as their focus had shifted to the resolution of pressing issues. Coupled with the adjustment to work-from-home arrangements and personnel changes in critical official roles, discussions, and decisions to guide the Ama Krushi transition slowed.

At a meeting in March 2021, the government committee, chaired by the then Principal Secretary, met to decide what form the Ama Krushi transition would take. Early considerations had included embedding government staff within the Ama Krushi team, but given the complexity of operations, the government indicated a strong preference for a procurement process to contract out management of the service to a third party, while retaining government oversight and ownership. Naturally, this development led to a series of internal considerations. What form would the transition now take? How would the third party engage with the government and the program? What would happen to program staff who had been trained with a view of being transitioned to government management? How would the service remain government-owned and -funded in the long term?

After exploring the route of procurement via impaneled agencies with the Government of Odisha, PxD and DAFE came to the conclusion that, given the size and complexity of Ama Krushi and its teams, the identification of a new implementing partner would require a full public procurement process facilitated by a request for proposals (RFP). 1An RFP is essentially an open tender:an advertisement for a service that the government requires (in this case, the management of the Ama Krushi program) is put out for a minimum period of time with a set of eligibility criteria. It invites bidders to submit a tentative budget and uses a careful scoring system to identify the best-qualified party for the task. In July 2021, the government published an RFP inviting candidates to take up the tender. The plan of transitioning the service in 2021 seemed unlikely.

The PxD team running Ama Krushi was funded by both BMGF and DAFE and comprised “ground teams” running everyday operations like profiling, content delivery, fieldwork, and IT maintenance, in addition to a dynamic data and management team. The RFP proposed a different model: the entire program would now be funded by DAFE, with the management team comprised of a Program Lead – to be filled by a government official – in charge of a program management team staffed by the organization identified through the tender, who in turn would manage the work of the ground/operational teams. We had expected that the ground teams would remain in place given that they are critical for program continuity, but there was no guarantee that the new entity would absorb the existing operational team. Suddenly, the future of our 120-people strong operational team looked uncertain.

Handover to Tatwa

Given the repeated delays and shifting parameters of the transition, we agreed with DAFE and BMGF to further extend the transition timeline to 31 March 2022.

At the conclusion of the RFP process, the government appointed Tatwa Technologies Limited as the third-party firm to take over Ama Krushi’s management and operations. Following the announcement, PxD facilitated an extensive capacity-building program premised on in-person workshops and intensive shadowing. Tatwa wisely chose to retain the program’s existing ground teams, ensuring that Ama Krushi’s operations would run smoothly, with little to no inconvenience to Ama Krushi’s now 3.1 million farmers. On 31 May 2022, PxD successfully transferred the day-to-day management of the Ama Krushi program to Tatwa Technologies. After an additional two months of technical support, PxD is no longer involved in the delivery and development of Ama Krushi’s services.

Needless to say, building and then handing over the program has been an immense learning experience. Odisha farmers relied on traditional knowledge for generations to navigate challenges associated with drought, cyclones, and other input-based complexities. Ama Krushi attempted to complement this traditional knowledge with an agricultural digital extension service capable of delivering credible, scientifically validated, and evidence-based digital information to improve decision-making, agricultural productivity, and smallholder livelihoods. We scaled a program from 50,000 farmers in 2018 to over three million in 2022, from one crop to 29 value chains spanning crops, livestock, and fisheries – all with the support of a growing team of content experts, field coordinators, and surveyors. Today, we can proudly say that Ama Krushi is an entirely government-funded and government-owned service running at scale. The transition formally concluded on 31 July 2022.

A fond farewell

Building a successful digital extension service like Ama Krushi and overseeing its successful handover was the product of years of hard work and effort. The learning curve has been steep, with unexpected accelerations in the ascent, as well as detours and changed plans. No success would have been possible without the active and sustained support of the BMGF and all of the government officials from DAFE. As a team, we learned to consistently check our assumptions and biases, systematically plan for contingencies, tailor our communications, manage expectations, and make ourselves more attuned to context-specific nuances. We will catalog these learnings as part of the post-transition monitoring exercise to inform future transition efforts (both internal and external) and provide insights for different use cases. We hope to leverage active learning from this transition to identify best practices for laying a foundation for a successful transition during the build and operate phases of development, and for successfully executing transition as the fulfillment of the build, operate, and transfer design.

Accurate, medium-range weather forecasting information can help mitigate smallholder farmers’ exposure to climate-related risks. PxD is in the process of launching new products to assist smallholder farmers to make more informed and timely decisions based on weather information. In this post, we outline the contours of our exploratory research to integrate weather forecasts into Coffee Krishi Taranga (CKT), our existing digital advisory service for small coffee farmers in India.

Coffee is a notoriously fickle crop. For example, heavy rainfall can damage crops, result in premature fruit-drop, increase the incidence of pests, and wash away fertilizer with negative implications for plant nutrient levels. Increasing weather variability and the incidence of extreme weather events associated with climate change will have significant negative effects on coffee producers. Given the sensitivity of the crop — and yields — to fluctuations in the weather, coffee farmers are likely to derive meaningful benefits from accurate and timely weather forecasts. Insights from our CKT learning agenda will be used to inform the design of a larger evaluation of the weather-integrated service and to scale an enhanced service to over 150,000 coffee farmers across four Indian states (Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh – an expansion state).

The motivation

PxD delivers CKT in partnership with the Coffee Board of India and with support from the Walmart Foundation. Since 2018, CKT has delivered a two-way interactive voice response (IVR) service with two principal components: an outgoing push call service that provides regular advisory to coffee growers via their mobile phones, and an inbound hotline that farmers can call to access free information services. In April 2022, CKT reached just over 70,000 smallholder coffee farmers in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

More accurate information about medium-term rainfall — with a lead time of up to 15 days — will enable farmers to make informed decisions about applying nitrogen fertilizer and increase the likelihood that they apply this input during dry spells to reduce run-off and leaching. Similarly, if farmers are alerted to impending heavy rain, they can leverage this information to alter harvesting times or take other precautionary measures to protect crops and insulate yields.

Speaking to farmers to inform design and process

In interviews conducted with coffee growers in August 20211 Described further in an earlier blog post that outlined findings from the landscape analysis of coffee production in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh relating to sustainability, market linkages, and gender., only 16% of respondents reported accessing forecasts (N=73). Integrating weather information into CKT’s existing services will broadcast weather forecasts to farmers tailored to their specific contexts and complement these forecasts with agronomist-designed advice. Exploratory and pilot research will be implemented between May and December 2022 in three important coffee-growing districts in Karnataka: Chikmagalur, Hassan, and Kodagu.

Studies conducted in other contexts find that farmers form subjective expectations about upcoming weather events based on various factors, including their past experiences, local rules of thumb, existing forecast information, the costs and benefits of acquiring such information, and perceptions about how relevant weather-related risk is to their incomes2As demonstrated in Giné, X., Townsend, R.M., & Vickery, J. (2015). “Forecasting When it Matters: Evidence from Semi-Arid India.” Working Paper.. These expectations inform behavior over the course of the coffee crop cycle as farmers make decisions relating to input and investment choices, the timing of activities, and so on. The sum of these decisions, in turn, influences outcomes that farmers (as well as researchers and practitioners) are interested in – notably plant health, yields, costs, and profits. The goal of this research is to understand each of these elements through measurement and service pilots, A/B tests, qualitative interviews, and in-person workshops with farmers, agronomists, and extension agents.

Coffee laborers having lunch on a coffee farm.

Iterating relevant service design and a weather service at scale

Commencing in May 2022, we will conduct multiple rounds of in-depth qualitative interviews with men and women coffee farmers. The sample will include farmers working a range of landholding sizes and will include both smartphone and feature-phone owners. The objective of the first set of interviews is to better understand how coffee farmers make decisions relating to the timing of agronomist-identified, weather-dependent coffee activities: fertilizer and lime application, coffee pruning, shade regulation, and harvesting. We hope to identify how weather fits into these decisions and what other factors influence the timing of these activities. If other limiting factors (such as the availability of an input) impact timing to a greater extent than the weather, forecast information with short lead times may not help farmers optimally time their practices without access to complementary inputs or information. These interviews will also help us identify how farmers interpret weather forecasts they already have access to, what impact incorrect forecasts have on their activities and on their trust in forecasts and the extent to which farmers discuss their expectations of upcoming weather with other members of their communities.

As detailed in previous blog posts about our weather-related work, PxD is partnering with leading private forecast provider CFAN (Climate Forecast Applications Network) to develop calibrated custom forecasts. Using weather forecasts from CFAN provides access to a continuous stream of information, which includes the numerical quantity of a rainfall event being forecast, numerical probabilities associated with a forecasted weather event, and error margins on the quantity of rainfall forecast for each of the upcoming 15 days3Read more about our collaboration in this previous blog post. Building on the first set of qualitative interviews, we plan to assess (1) whether farmers comprehend and have an appetite for probabilistic and uncertain information; (2) whether specific forecast attributes or lead times meaningfully change farmers’ expectations of upcoming weather; and (3) which combinations of attributes and lead times aid decision-making for each weather-dependent activity. We plan to gauge farmers’ understanding of probabilities and uncertainty in a second set of in-person interviews to whittle down the forecast formats that will be most useful in this context.

PxD facilitated Interviews with coffee growers.

Coffee farmers in a subset of villages in our three study districts will then be invited to participate in in-person workshops, where they will interact with different forecasting formats. The workshop will be in the form of a ‘lab-in-the-field experiment’, where participants engage with an interactive platform that presents weather forecasts together with incentivized agricultural decision-making scenarios. Utilizing participants’ decisions on the platform, an ‘in-scenario’ weather ‘realization’ will be simulated, allowing participants to accrue a higher payoff for a ‘better’ decision. The best-performing forecast will accrue the highest cumulative payoff across participants and will inform our understanding of which forecast formats most effectively aid decision-making. The ‘best-performing’ customized-to-context weather forecast will then be piloted in the field among a sample of existing CKT users to evaluate whether it improves decision-making in a real-world setting.

Delivering an effective weather-based advisory service via mobile phone also requires that we ensure that users engage with and use the information being delivered. To this end, we plan to run A/B tests to optimize the frequency with which weather forecasts are delivered, the length of messages, and other service features.

We are optimistic about the utility of weather forecasting information and its potential impact on smallholder farmers — and their productivity — as they make what we hope will be more informed decisions. We are excited to deploy this information and make it actionable for smallholder coffee producers on our CKT service. Watch this space!

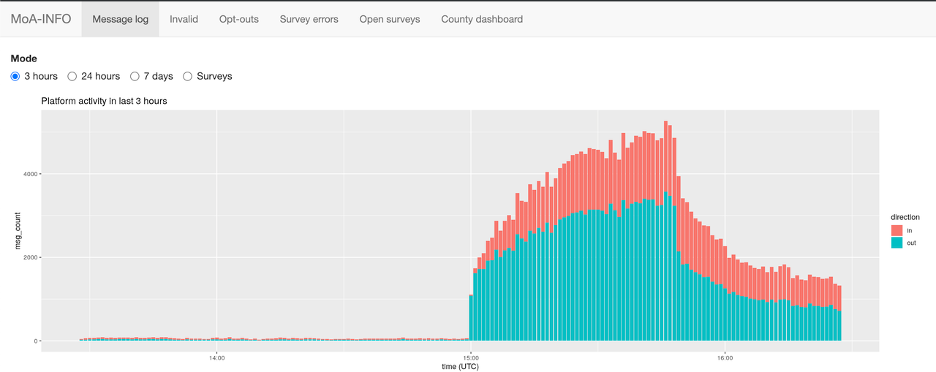

Uzoamaka Ugochukwu, PxD’s Nigeria Country Launch Manager, was selected to present a “tech demonstration” at the 2022 rendition of the Global Digital Development Forum. The demonstration presents how PxD leveraged our in-house tech platform, Paddy, and our experience implementing digital advisory services to rapidly build, deploy and scale services to 107,000 smallholder farmers in Nigeria.

PxD’s forthcoming 2021 Annual Report will be conveyed primarily via video using a similar design to that deployed in this video. Watch this space!

Precision Development (PxD) leverages needs assessment research to inform our agricultural extension services, and we survey our farmers to gauge their opinion of our services. Sourcing information from farmers gives us direct insight into the challenges and opportunities farmers face. We use these insights to improve the design of our services and the content of our advisory messages in an effort to align them most closely to farmers’ informational needs.

Through the course of 2021, as we designed and rolled out a new advisory service for farmers in Nigeria, we conducted five surveys to inform more evidence-based decision-making:

- Baseline survey (Jan 21)

- Dry season feedback survey (7th April)

- Wet season feedback survey (3rd August)

- Wet mid-season adoption and knowledge survey (20th August)

- End-line survey (December – analysis is ongoing)

Having a clear line of sight into the needs of farmers has been critical as the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved and created new and shifting challenges for farmers in remote areas.

At PxD we believe the information revolution and the spread of mobile technology to people living in poverty offer unprecedented opportunities for increasing access to information at scale and at a very low cost. We promote digital information-sharing systems to distribute quality, actionable and targeted information. By obtaining regular feedback from farmers through research in behavioral economics and social learning our services are improved to encourage the adoption and assimilation of practical information and improved or adapted production practices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gathering Insights on Farmers’ Needs

Utilizing an emergency grant from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), PxD began working in Nigeria in November 2020 – eight months after the World Health Organization’s assessment of COVID-19 as a “pandemic”. PxD’s initial service, delivered during the dry season, reached more than 5,000 smallholder farmers within three months of the program’s launch. The service was then scaled to serve more than 100,000 users during Nigeria’s primary growing season, the wet season. PxD collaborated with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) to implement the Nigeria Rural Poor Stimulus Facility (RPSF), funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). IFAD’s funding objective was to assist Nigeria to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on smallholder farmers and its goal was to insulate domestic food supply by supporting access to affordable inputs and advisory to sustain production.

We believe that gathering baseline information from farmers about their needs was a critical factor that contributed to the success of PxD’s digital advisory service in Nigeria. We conducted a baseline survey in January 2021 to collect information on:

- Farmers’ socio-economic, demographic, and institutional characteristics;

- Their knowledge about dry season cultivation of crops and Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs); and

- Their perception of and willingness to receive mobile advisory services.

The survey interviewed 254 farmers randomly selected from a database of over 5,000 farmers. Findings from the baseline survey showed that 95% of the respondents indicated they would be interested in planting during the dry season. The remaining five percent identified lack of water and access to land as major barriers to engaging in any planting in the dry season. The survey also revealed that a lack of appropriate inputs, pests and disease problems, personal preferences, bad harvests, distance from water, and knowledge gaps are important challenges for the smallholder farmers.

Listening to the Farmers from the ‘Get-go’!

At PxD, we prioritize offering our users valuable and practical information to change or improve farmer behaviors and farm productivity. We do this by providing information customized – wherever possible – to a farmer’s location, market conditions, and personal characteristics. To calibrate our systems effectively, it is essential that we hear from the farmers themselves to understand their needs as they relate to their socio-economic realities. The results of our dry season baseline survey provided useful insights about farmers’ crop choices as well as their previous or existing crop practices. This information was vital for informing our product development and service delivery.

Only 56% of farmers surveyed during our baseline assessment had ever attended any training or workshops on crop production techniques. The survey also revealed that rice was the preferred crop for the dry season, followed by onions, tomatoes, and other vegetable crops. These and other findings helped us develop recommendations for specific topics, crop value chains, and farmer groups.

While just over half of farmers surveyed at baseline had experienced some kind of extension outreach, the advisory content received varied. For example, fewer than 50% of farmers had received training on GAPs such as:

- Weed management;

- Harvest and postharvest handling;

- Water management;

- Nursery establishment;

- Transplanting; and

- Input selection.

Whereas more than 50% had received training on:

- Pest and disease management;

- Fertilizer application; and

- Land preparation.

Importantly, the team also learned that fewer than 50% of the respondents had applied any of the GAPs or any other training they had received.

Monitoring Farmers’ Engagement and Feedback

One crucial aspect of our work at PxD is to gather evidence on the impact of our services on smallholder farmers. We are a learning organization that rigorously tests our services through experimentation and research. We have a high level of flexibility to adapt to the complexities of the various geographies where we work. Regular monitoring and evaluation of our interventions help us understand how our services are impacting our users and give us early insights into potential problems. PxD incorporates insights from behavioral economics, human-centered design, and social learning theory, and uses A/B testing and data science to identify what types of information and delivery mechanisms work best for our users.

In Nigeria, a feedback survey was conducted at the end of the 2021 dry season to assess farmers’ perceptions and use of the push call services, and to analyze factors that influenced their engagement with the service. The sample comprised 700 farmers randomly drawn from the seven states where the service was provided (Borno, Jigawa, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara). The sample distribution was 500 farmers from the ‘high participation’ group (with a more than 50% average listening rate) and 200 farmers from the ‘low participation’ group (with a less than 50% average listening rate). The survey results indicated that 88% of respondents, or a member of their family, recalled listening to any of the push call messages, while 86% reported “continuing to listen” to the calls (a proxy for continued engagement). This was particularly significant as it was the first season of the PxD program in West Africa.

Furthermore, a knowledge and adoption survey conducted in August, during the wet season campaign, indicated that 85% of respondents reported adopting at least one GAP, while 95% of respondents correctly answered one or more of the five knowledge questions asked in the survey. The survey also measured service satisfaction. Analysis of the survey results revealed a positive net promoter score of 39 (on a scale of -100 to 100), indicating that a majority of respondents (53%) said that they were likely to promote the service to other users, while only 14% of the sample reported being unlikely to recommend it or continue using the service.

To achieve behavioral change, the information conveyed should be accessible and of practical use to rural farmers. Ninety-four percent of respondents to the wet season feedback survey answered ‘Yes’ when asked: Were the messages clear and loud enough so that you could understand their content? In addition, 96% confirmed that they or a household member adopted the agronomic advice during the planting season.

Research shows that access to extension services is a key driver of technology adoption. Farmers are usually informed about new technology and its effective use by extension agents (Genius et al., 2010). Furthermore, the extension agents form a link between the researchers and users of the information, which helps to reduce transaction costs incurred when passing on the information about the new technology to a large heterogeneous population of farmers (Genius et al., 2010).

However, in-person extension services are expensive and time-consuming to deliver, and very difficult to scale. One can’t copy-and-paste trained extension agents, or their means of transportation, or guarantee that when extension agents make contact with a farmer the information they carry with them will be temporally valuable or practical. As evidenced by feedback from our farmers, very few Nigerian smallholder farmers have benefitted from extension services in the past. Feedback from farmers suggests that PxD’s model of digital agricultural extension in Nigeria, implemented in collaboration with partner organizations to maximize scale and at very low costs per farmer served1 Our Nigeria service was delivered at an average annual cost of $3.45 per farmer served, which compares extremely favorably with the costs of in-person extension services. With further scaling, we expect this number would fall further, and more closely align with PxD’s average cost per user served which at the time of writing was $1.61 per user per year., was considered by farmers to be valuable and relevant. Many farmers reported implementing the advice we broadcast to them. Digital delivery channels meant that we were able to deliver extension services under pandemic conditions when human movement and personal interactions were limited or prohibited.

The success and rapid scaling of our Nigeria service were built on strong partnerships, a portable and customizable in–house technology platform, and a service delivery model that we constantly update with information sourced from the farmers we serve, the results of surveys and experimentation, and rigorous evidence on the impact of our work. We look forward to building on our Nigerian successes and further assisting farmers in need as they confront wide-ranging challenges in very difficult conditions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the RPSF financial support of IFAD. Many thanks to the Nigerian team for their collective effort in drafting this post, and Emmanuel Bakirdjian, Theresa Solenski, Moira Levy, and Jonathan Faull for their contributions.

References

Balana B.B., Oyeyemi M.A., Ogunniyi A.I., Fasoranti A., Edeh H., Aiki J., and Andam K.S. (2020). The effects of COVID-19 policies on livelihoods and food security of smallholder farm households in Nigeria: Descriptive results from a phone survey. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1979. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.134179

Mungai L.M., Snapp S., Messina J.P., Chikowo R., Smith A., Anders E., Richardson R.B., and Li G. (2016). Smallholder Farms and the Potential for Sustainable Intensification. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01720

Paul A. Francis, John T. Milimo, Chosani A. Njobvu, and Stephen P. M. Tembo (2013). Listening to Farmers. Participatory Assessment of Policy Reform in Zambia’s Agriculture Sector. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-4025-5

Genius, M., Koundouri, M., Nauges, C., and Tzouvelekas, V. (2010). Information Transmission in Irrigation Technology Adoption and Diffusion: Social Learning, Extension Services and Spatial Effects. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aat054

Precision Development’s goal is to generate large aggregate impacts for the poor. Research plays a central role in advancing that objective. In a collaborative post, our Research Team surveys their work in 2021 and outlines an exciting portfolio of activities planned for 2022.

As a recent video produced by our colleagues at J-PAL recounts, Precision Development would not exist were it not for the practical application of research in the world. By intentionally deploying experiments and other methods, we continue to use research to inform the design of our services (innovation research) and to evaluate our impact (evaluation research), and these two types of research often overlap. PxD’s research practice aims to integrate with service design and delivery, and we leverage research to iterate our theory of change, identify learning objectives, and gather insights in every program and initiative.

Needless to say, in 2021 we were busy! Our research and operations teams have collaborated on 26 experiments, of which 14 are completed and 12 are ongoing.

Evaluation Research

At the end of 2021, PxD has three ongoing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to rigorously evaluate the impact of our services on downstream user outcomes, such as the adoption of improved farming practices, improved agricultural yields, or impacts on learning. In addition to these three evaluations of our own services, we are collaborating with One Acre Fund (OAF) to evaluate aspects of their work with Farmer Promoters.

Excitingly, PxD is running a large-scale RCT with nearly 15,000 rice farmers in India to estimate the impact of the Ama Krushi service on farmers’ practices and yields, and how the magnitude of these impacts vary by farmer characteristics. Data on production costs and revenues will be collected from a subset of farmers for a back-of-the-envelope calculation on the service’s benefit-cost ratio. This RCT also aims to test the effectiveness of using satellite-based imagery to detect yield changes in GPS-measured smallholder rice plots and to compare these to self-reported farmer yields. Early in 2022, we will conduct the midline survey and process satellite images to assess the impact in the first season. We are eager to share our initial findings!

In western Uganda, PxD is collaborating with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the Hanns R, Neumann Stiftung (HRNS), and Technoserve to measure the stand-alone impact of PxD’s two-way voice-based advisory service and the complementary impact of digital reminders implemented by PxD as part of the Uganda Coffee Agronomy Training (UCAT) program. This RCT plans to integrate the use of machine learning to identify agricultural practices that have the highest impact on improving coffee yields and to identify farmer characteristics that are most closely associated with the increased adoption of such practices. The COVID-19 pandemic pushed back the initial implementation schedule for UCAT and we now plan to collect endline data for approximately 4,000 farmers in 2022.

In the education sector, Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and PxD have concluded data collection for a randomized evaluation to assess the impact of our two-way SMS math education service, ElimuLeo, on learning and knowledge. Implementation of the RCT has now concluded and we have extended access to the platform to children in the control group. We have recently surpassed the milestone of over 500,000 problems solved on the platform!

Since 2018, PxD has partnered with One Acre Fund (OAF) to test low-cost incentives to enhance the performance of approximately 11,000 Rwandan volunteer extension agents, commonly known as Farmer Promoters (FPs). With one FP in each of Rwanda’s 14,500 villages, PxD’s collaborative intervention targets a majority of FPs in the country. Importantly, FPs do not receive monetary compensation for their service, but rather receive in-kind benefits such as free inputs. Throughout 2021, PxD and OAF have been conducting an RCT to examine whether motivational SMS messages improve FPs’ performance, and to test whether motivational messages designed to appeal to the FP’s specific personality traits lead to improved FP performance and farmer outcomes. This evaluation includes three main interventions: a subsidized input promotion campaign, a demonstration plot and farmer training campaign, and an agroforestry tree planting campaign. We aim to launch endline surveys in early 2022.

Service Design and Innovation Research

As part of our efforts to leverage research to improve service design and delivery, we often conduct rapid hypothesis testing. We are also exploring ways of increasing engagement with our Ama Krushi push call service. In 2021 we deployed an A/B test that experimented with sending “heads up” SMS messages at different times to alert farmer users of an impending IVR call from the Ama Krushi service. Results are very promising: sending an SMS reminder 10 minutes before a service call increases pick-up rates by 5.9 pp (a 17% increase from the control mean pick-up rate of 34%). Conditional on picking up, the 10-minute SMS reminder also increases average listening rates by 4 pp (a 25% increase over a control mean of 15.4%). Considering both the success of the 10-minute reminders and the relatively high costs of sending SMS messages via the Ama Krushi service, one implication of this experiment would be to send short SMS reminders to farmers who are at risk of becoming inactive on the service to nudge engagement for a limited period and to promote recommendations that have particularly high-impact or are time-sensitive.

Reminders also play an important role in nudging farmers to take action on optimal planting dates. Planting at the optimal time is positively correlated with yields, yet misconceptions, lack of knowledge, or limited resources often result in farmers planting at a later date. In the 2021 Long Rains season in Kenya, we tested whether sending SMS messages recommending optimal planting times would nudge adoption. This experiment targeted a sample of approximately 15,000 OAF farmers and included additional treatments such as messages addressing misconceptions on planting times and direct endorsements from Field Officers. We found that SMS recommendations for optimal planting times are effective in nudging average self-reported planting dates closer to the optimal date. This effect is larger for late planters. Late planters in treatment groups reported planting, on average, four days closer to the optimal date relative to the late planters in the control groups. These results are valuable for improving service delivery in Kenya and for nudging farmers toward more timely planting. We are keen to conduct further research on the mechanisms underlying planting time decisions.

A/B tests deployed by PxD have shown that a narrator’s voice can impact user engagement in various contexts. In 2021 we completed a first A/B test on our nascent program in Nigeria to measure the effect of the narrator’s gender on pick-up and listening rates for PxD’s push call platform. Over the course of a seven-week period in the Wet Season, a sample of over 45,000 farmers was randomly allocated into two groups, receiving weekly audio content narrated either by a female or male voice, respectively. We found that female farmers have systematically lower pick-up rates than male farmers, yet this gap is slightly mitigated when the narrator is female. In addition, we found that all farmers (both male and female) when listening to content voiced by a female narrator were 1.4 pp more likely to listen to the full push call, given a mean completion rate of 51.8% of the audio content. Going forward, our service in Nigeria will primarily use female narrators when recording audio content for push calls. Nevertheless, we will benefit from further research to generate evidence on the long-term effect of this action on user engagement.

Our nascent research agenda in our newest program in Colombia is leveraging past experimentation on human contact and direct endorsements, particularly when it comes to increasing user engagement in the early stages of service delivery when name recognition and trust levels are limited. We have recently concluded profiling surveys and are analyzing how user engagement with PxD’s Un Mensaje por El Campo platform varies before and after farmers receive the profiling survey. SMS messages are not broadly used by smallholders in the Meta region of Colombia and many farmers need to be guided on how to access and navigate their SMS inbox to realize that they have been receiving messages from our service. Surveys and direct contact with surveyors from our team provide an opportunity to mitigate low digital literacy and improve trust in our service.

Moreover, we continue to explore ways to support farmer access to recommended agricultural inputs. In Kenya, we are building a proof-of-concept digital tool to improve linkages between farmers and agro-dealers by providing local agro-dealer contact information on our MoA-INFO platform. This digital Agro-dealer Contact Directory (ACD tool) will help us gather insights on the perceived value of reducing search costs among farmers and agro-dealers, as well as potential effects on farmers’ input search behavior and input access. Using these insights, we can then determine if there are other low-touch, scalable engagements with agro-dealers that will help us to improve farmers’ welfare. Drawing on the evidence from the literature on digital phone books, we have launched a two-way agro-dealer pilot with over 33,000 MoA-INFO farmers and 142 agro-dealers. This pilot aims to elicit feedback from farmers and convey information about their input demand to agro-dealers, mitigating informational barriers that prevent agro-dealers from consistently stocking inventory. Farmers are often uncertain about which inputs are in stock and agro-dealers are uncertain about quantities of inputs demanded by farmers, with many reporting being out-of-stock during peak times of the year. Stock-outs raise uncertainty and search costs for farmers and can lower adoption rates for improved inputs, especially if farmers have to travel far to other markets. Experimentation with the ACD tool aims to reduce search costs and improve access to recommended inputs.

Crowdsourcing local information from farmers and other actors along the agricultural value chain holds many potential advantages for our services. The key is to identify scalable ways to crowdsource sufficiently granular information to improve the quality of our advisory content. In Gujarat, we are generating insights on the operational feasibility and scalability of collecting accurate and timely information on crop health issues from locally recruited gig workers and tracking the volume and quality of data submitted by these workers via a tailored WhatsApp chatbot.

Finally, sourcing and providing information on pest prevention and management continues to be one of our research priorities. We are particularly excited about an ongoing pilot in Karnataka, India, which is reinforcing good management practices for white stem borer, a major coffee pest. In a recent round of qualitative surveys, we found that a majority of respondents had experienced white stem borer infestation in the previous coffee season, and many farmers reported using antiquated corrective measures that are no longer recommended by the Indian Coffee Board, or even practices that have been banned. Research undertaken in 2021 on Fall Armyworm infestation in Kenya and Zambia, provides some indicative evidence that our advisory increases knowledge and adoption of recommended pest prevention and management practices, and that sending reminders for priority practices may result in higher knowledge and adoption. Building on this evidence, we are partnering with J-PAL to test whether repeating key advisory messages on white stem borer and using different types of reminders and nudges, lead to higher rates of adoption for recommended practices among a sample of 2,400 coffee farmers. This experiment is ongoing and we aim to share results by mid-2022.

Looking forward to exciting research opportunities in 2022

Throughout 2021, PxD expanded dairy and livestock advisory services in Kenya, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and India. In Kenya, we are partnering with three dairy cooperatives to iterate and build a two-way SMS advisory service for dairy farmers. Building on the results of a gender survey to assess the gendered division of labor within dairy-producing smallholder households, we are excited to commence an RCT of the service in early 2022, ahead of the Long Rains seasons. We aim to rigorously evaluate the impact of the service on milk production (both in terms of quality and quantity) and sales for a random sample of 5,000 dairy farmers using administrative data made available from our dairy cooperative partners.

Finally, we are excited about our nascent climate research agenda, which includes both adaptation and mitigation efforts, and aim to continue scoping opportunities within our services and geographies to strengthen smallholders’ climate resilience, generate scalable low-cost climate mitigation innovations, and, above all, to improve smallholders’ agricultural productivity and income. We are excited to launch new products integrating granular weather forecasting with actionable advisory in Punjab, Pakistan, and Karnataka, India. Our weather pilots aim to incorporate innovation research to understand how to communicate uncertainty and probabilistic events in low-literacy settings, as well as the value of forecasting versus tracking advisory. Moreover, after recently securing new climate mitigation funding, we are eager to conceptualize research pilots to measure low-cost scalable innovations and rigorously measure changes in both farmer and climate outcomes. We intend to establish a proof of concept for our environmental theory of change and seek further validation of the applicability of PxD’s communication for behavior change model on new research areas, such as the potential for cash payments to farmers for activities that sequester soil carbon and contribute to climate change mitigation efforts.

At PxD our decision-making draws on existing evidence and scientific knowledge; understanding about how humans, institutions, firms, and markets behave and function; contextual information and knowledge about targeted users and local conditions; and our prior experience (as well as resource envelopes and other pesky exogenous factors). Research and inquiry are critical to generating insights and uncovering new information across all of these categories of knowledge. We are privileged to work with colleagues who rigorously generate and leverage evidence to guide our work and decision-making as we develop, iterate, and scale innovations that impact poverty at scale.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2022!

Can e-commerce address constraints that inhibit growth and productivity among Indian smallholder farmers? Rohit Goel, a Research and Operations Associate on PxD’s India Team, investigates and traces the contours of an exciting PxD pilot in Gujarat which aims to connect smallholder farmers to online vendors and marketplaces.

E-commerce – the buying and selling of goods and services over an electronic network – has transformed business operations in India. In 2020, the market size of e-commerce in India was assessed at 64 billion USD in 2020 and is expected to rise to 200 billion USD by 2027. This rapid growth in e-commerce has the potential to address long-standing deficiencies in the Indian agricultural sector, and transform Indian agriculture – a sector that accounts for 18.3% of India’s GDP (2020) and is the primary source of income for a majority of Indian households. This opportunity presents itself at a time when the sector is declining in productivity due to a range of challenges including a constrained supply of inputs, inefficient sales markets, and low levels of competition among intermediaries across supply chains. However, India’s agriculture sector is poorly positioned to capitalize on the opportunities presented by e-commerce due to challenges confronting smallholder farmers in rural areas, such as low levels of digital literacy, poor ICT infrastructure, a lack of familiarity with digital transactions, and inequitable access to smartphones and/or the internet.

Precision Development (PxD) is well-positioned to assist firms and farmers overcome these and other access and market-related challenges. With support from the Swiss Re Foundation, we are utilizing our voice-based, two-way information exchange service – dubbed Krishi Tarang – to pilot an initiative to inform farmers about, and connect them with, a variety of businesses that address unmet needs at different points across the agricultural value chain – including, but not limited to, input suppliers, crop offtakers, lending agencies, crop insurance providers, soil testers, and carbon traders. Krishi Tarang operates using Paddy, PxD’s in-house communications platform, and is compatible with very basic mobile phones that lack internet capabilities. The pilot will also explore revenue generation opportunities to support the scaling of free, customized, and timely agricultural advisory services to smallholder farmers and endeavors to complement the work of other not-for-profit organizations working to improve farmer livelihoods so that their farmers can take advantage of these new partnerships too.

Creating an online ecosystem for smallholder and village farmers

With support from the Swiss Re Foundation, PxD is working to holistically address farmer needs by creating an ecosystem of private partners along the agricultural value chain. Moreover, we are investigating ways in which new partnerships can generate revenue to support free digital agricultural advisory services for smallholders. The successful implementation of an integrated service offering at scale has the potential to reduce farmers’ overall costs while enhancing their revenues. We also hope that this initiative will generate new insights that help us to make our advisory service more relevant and, by extension, improve adoption rates of PxD’s recommendations among farmers.

Since December 2020, PxD has run a pilot project with farmers registered on our Krishi Tarang advisory service in Gujarat. As part of the pilot, PxD contacts farmers via channels, such as automated and live calls, to promote the services of our partners. Farmers who show interest in a particular service are then connected to service providers. PxD takes a nominal commission on every successful transaction initiated by Krishi Tarang farmers and, in certain instances, a fixed fee for connecting each new farmer. In this way, PxD’s farmers can connect with a series of legitimate e-commerce partners to access various goods and services such as business development and market linkages, agricultural inputs, financial support, and field-level technology. Since the farmers do not need an internet connection or smartphone to access these services, we can circumvent some persistent barriers to entry and access, and connect marginal and smallholder farmers to online vendors. We hope that competition among vendors will improve and draw an increased number of users and service providers to the village and smallholder marketplace.

E-commerce’s transformative potential

In 2016, 59% of India’s workforce was employed in agriculture. In rural areas, dependence on farming activity is widespread, with 70% of households relying on agriculture to support their livelihoods. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 82% of India’s farmers are small and marginal farmers. Despite the importance of agriculture for so many Indian households, the contribution of agriculture to GDP has fallen precipitously in recent decades, declining from 41.3% in 1960 to 18.3% in 2020. Given the large share of Indian households that continue to depend on agriculture to support their livelihoods, and the number of poor households dependent on the fortunes of the sector in particular, declining productivity and profitability in the sector is a significant concern.

E-commerce has the potential to address several challenges constraining the performance of India’s agriculture sector by creating new links between participants along the agricultural value chain. Examples of potential benefits include:

- Waste reduction: According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a third of food produced for human consumption is wasted. A study by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research in 2016 reported losses of approximately 5.5% for cereals, pulses, and oilseeds, and approximately 11% for fruits and vegetables, due to waste during harvesting, post-harvesting, handling, and storage. Agriculture e-commerce services can reduce post-harvest waste by minimizing the number of intermediaries farmers need to liaise with, improve access to more efficient transportation, and quicker access to quality storage facilities. At the aggregate level, these effects can substantially reduce the time it takes for produce to reach consumers.

- Overcoming information asymmetries: There is some evidence that mobile phones improve farmers’ access to information with potentially positive implications for their incomes, although the findings are mixed. Muto & Yamano (2009) found that increased phone coverage in rural Uganda, between 2005 and 2009, was associated with a higher probability of banana sales and an increase in the sale price of bananas. However, this pattern was not evident for maize, a non-perishable crop, suggesting that price information may be more important for products with a shorter shelf life. Jensen (2007) found that the introduction of mobile phones in Kerala was associated with an increase of 8% in fishermen’s profits, driven by reduced wastage. However, other papers have found little impact of ICT on farm prices and farmer income. For example, Aker and Fafchamps (2015) examined mobile phone expansion in Niger, and Futh and McIntosh (2009) examined the introduction of village phones in Rwanda. Neither evaluation found evidence that increased access to phones was associated with price changes.

- Financial inclusion: When agricultural e-commerce platforms store transaction records, they may offer farmers an opportunity to build a “digital history” that could, in turn, allow them to demonstrate farmers’ creditworthiness to financial service providers. Francis, Blumenstock and Robinson (2017) identified credit scores, captured from the historical user data using mobile phones, as one of the major factors leading to creating a digital credit system. Digital credit lowers transaction time and reduces costs compared to conventional credit, and borrowers generally do not need collateral to be approved for digital loans. According to GSMA’s report, in 2018, 866 million people have mobile money accounts processing 1.3 billion USD daily. Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 45.6% of the mobile money activity in the world; and technology companies, credit bureaus, and banks are opting for smartphone digital credit scoring for their business.

- Improved cost and market efficiency: The potential economic benefits of agriculture e-commerce may serve as an incentive for farmers to increase their on-farm investments and productivity. In addition, farmers may gain access to higher-quality inputs through online suppliers than they can find in their local markets. For example, Bergquist and McIntosh (2021) find that the introduction of a mobile phone-based marketplace for agricultural produce in Uganda led to increased trade flows and reduced-price dispersion across markets, generating a cost-effective increase in farmer profits.

Ongoing Challenges

Agritech startups and other private firms are leveraging technology to provide farmers with access to new input suppliers and improve linkages to output markets. The market for digital agriculture services in India has grown rapidly in the past few years, with companies like Ninjakart, Big Basket, Grofers Agrostar, and BigHaat raising millions of dollars in start-up capital.

Despite the actions of these and other stakeholders, and evidence of benefits associated with e-commerce, the take-up of e-commerce services to support the agricultural sector in India has been limited. Key challenges include:

- Rural India lacks infrastructure for e-commerce. 70% of the rural households do not have an active internet connection, and only 4.4% of rural households own a computer.

- Middlemen continue to play a dominant role in agriculture markets and rural economies. Poor market linkages increase transaction costs and post-harvest losses. Poor market development enables middlemen to dominate critical roles and transactions across the supply chain in such a way that only a very small share of the final sales price reaches smallholder farmers. Moreover, middlemen and money lenders at the local level may function as local monopolies, further depressing farmers’ bargaining power and the prices paid for produce.

- Underdeveloped cold chains and long transportation times limit the transport of perishable goods, increase post-harvest losses and constrain market development.

- Farmers are unable or reluctant to adapt to online opportunities. PxD conducted qualitative interviews with 119 farmers registered on PxD’s service in Gujarat and Haryana in March, April, and May of 2021. Ninety-six percent of respondents reported that they bought their inputs locally, citing the quality of the inputs received, trust in the seller, and credit availability as their reasons for doing so. Only 13 farmers (11%) had ever purchased agricultural inputs online.

- In 2018, more than 19,500 languages or dialects are spoken by Indians as their mother tongue. The diversity of spoken and written languages and cultures makes it difficult for small firms to scale their services.