2022 was a tremendous leap forward for research at PxD. Our research and operations teams completed a total of eight A/B test experiments and impact evaluations. We collected data in person and over the phone from approximately 20,000 survey respondents in 27 distinct surveys that took place in Kenya, Ethiopia, Colombia, Pakistan, and three states in India.

We generated new insights to build future programming such as an SMS agro-dealer directory to reduce input market information frictions, built evidence-based proofs of concepts for innovative service design such as WhatsApp-based crowdsourcing chatbot and learned to leverage research partnerships for scalability with dairy cooperatives. We used research insights to shift and refine our approach and we are excited about further impact evidence from forthcoming analysis in 2023.

Devastating events in 2022 from drought in the Horn of Africa to the 100-year flood in Pakistan emphasize that climate change is one of the most urgent challenges facing our users. As such, we have intensified our research efforts to identify interventions that can improve smallholder livelihoods whilst incorporating climate adaptation and mitigation efforts into our existing services. We’ll continue this innovation research agenda in the coming year to explore high-value innovations to supplement our core digital agricultural advisory.

New insights to build future programming

Across a diverse portfolio of research projects, we have demonstrated the value of PxD’s services and contributed to an expanded knowledge base on digital agricultural extension. A particularly promising finding is establishing that digital tools can be effective in improving in-person extension services.

Performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages could increase extension volunteers’ performance: Through a large-scale randomized evaluation in Rwanda, we demonstrated that performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages – particularly goals that were ambitious but attainable – could improve community extension volunteers’ (known as Farmer Promoters – FPs) performance and therefore generate positive impacts on farmers’ outcomes. Sending goal reminders to FPs significantly increased the number of farmers trained by 3.1 percent, led to a significant 4.3 percent more training sessions being delivered, and increased farmers’ registration for subsidized inputs by 1.9 percent (statistically insignificant) over FPs who did not receive goal reminders. Given that the unit cost for each SMS is $0.006 and the average number of farmers assigned to each of the ~14,000 FPs across Rwanda is 190, the effect sizes of these messages are likely to be highly cost-effective.

The results of the Rwanda project support the expansion and replication of extension agent interventions in other settings targeting different populations in the future. In addition, these results point to areas for future research and development that could enhance the effectiveness of extension agent services. For example, we are interested in exploring how digital tools can be used to help extension agents set performance-increasing goals, direct them to farmers most in need, and extend information access to farmer populations that may not benefit from direct digital advisory services.

A digital directory of agro-dealers has the potential to increase the adoption of recommended inputs: In Kenya, we found evidence that farmers can benefit from the provision of an SMS agro-dealer directory by reducing input market information frictions. Our preliminary empirical findings suggest that – particularly for a directory that includes stock and price information about agro-dealers – access to this tool prompts farmers to refine their choice of agro-dealers before an in-person visit. Farmers in the treatment arm who had access to the agro-dealer directory and stock information contacted 21 percent more agro-dealers, but visited 4 percent fewer agro-dealers relative to the control group which did not have access to the tool. This suggests that farmers in this treatment arm used the contact information to call more agro-dealers before spending time and money to travel to the shops themselves.

Farmers given access to the agro-dealer directory were more likely to purchase PxD-recommended inputs and experienced fewer stockouts than those who didn’t have access to the directory. When pooling the two treatment arms, we observe that consistent with PxD’s advisory recommendations, treated farmers were 6 percent more likely than control farmers to use hermetic bags to store maize – a practice shown in rigorous studies like Ndegwa et al. (2016) to prevent post-harvest losses from pests. Farmers in the treatment arm with access to the directory but not stock info appeared to contact and visit agro-dealers at the same rate as the control group but then were 22 percent less likely than the control group to report facing an input shortage when they shopped (meaning they were more likely to find and purchase the product they were looking for).

Building on these promising findings, we hope to identify opportunities to further develop a scalable digital agro-dealer directory tool. Specifically, we are interested in exploring ways to onboard a large number of agro-dealers and update the stock information at a low cost.

Building proofs of concepts

Digital peer groups increase farmer interactions and potentially increase the adoption of recommended practices, but we need creative ways to form groups at a low cost: Various research projects aimed to demonstrate proof of concept for novel interventions that PxD was exploring for the first time. For example, we now have empirical evidence that an intervention in Kenya to organize farmers into groups and send them SMS nudges to communicate with each other was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members. Treatment farmers who were organized into digital peer groups had higher interaction levels than their control group counterparts and were 43 percent more likely to meet with their group members on a farm than control farmers. Interacting with one’s group members on a farm was also associated with increased adoption and knowledge of recommended practices.

A gig-worker model for crowdsourcing agricultural field photos has the potential to generate real-time data on field conditions: We acquired institutional knowledge, both technical and regulatory, to build and operationalize crowdsourcing platforms to demonstrate the feasibility of crowdsourcing information from agro-dealers and farmers in Gujarat. In a pilot, we set up a WhatsApp chatbot, integrating a WhatsApp Business Account with our in-house user communications platform, Paddy, to guide users through a systematic inspection of a field for crop health issues and send reports back to PxD with their findings.

Eighteen of our recruited farmer agents consistently engaged with the program over 10 weeks, with a median of nine crop health reports per agent. The quality of field reports was high – approximately 94 percent of reports are usable. In total, we received 220 field reports with accurate GPS locations and usable photographs. Each of these reports costs INR 125 (USD 1.67), which is substantially below the cost of a 15-minute phone survey. This suggests that crowdsourced data could be a cost-effective method of collecting local data.

PxD aims to further build this knowledge to crowdsource various types of information and use it to improve future service offerings by customizing advisory to be more locally relevant and actionable.

Working with smallholder farmers in the fight against climate change

We are intensifying our efforts to provide information to smallholder farmers that will allow them to make informed decisions to reduce the risks that climate change presents to their livelihoods and to consider adopting practices that can actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We approach this work with the guiding principle of farmer welfare first: smallholder farmers cannot be expected to pay the price for climate change mitigation. Climate change-related advisory should directly support livelihood gains via improved agricultural output or renumeration .

PxD, in collaboration with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD), worked to assess opportunities to benefit poor farming communities through their participation in climate mitigation activities and to direct tangible returns to participating smallholder communities.

The PxD-IGSD collaboration has focused on exploring four mitigation areas with most promise in agriculture: Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced rock weathering; Carbon dioxide sequestration with organic carbon storage in soils and plant biomass; Nitrous oxide mitigation through precision nutrient management; and Methane mitigation in dairy through improved livestock feeding practices.

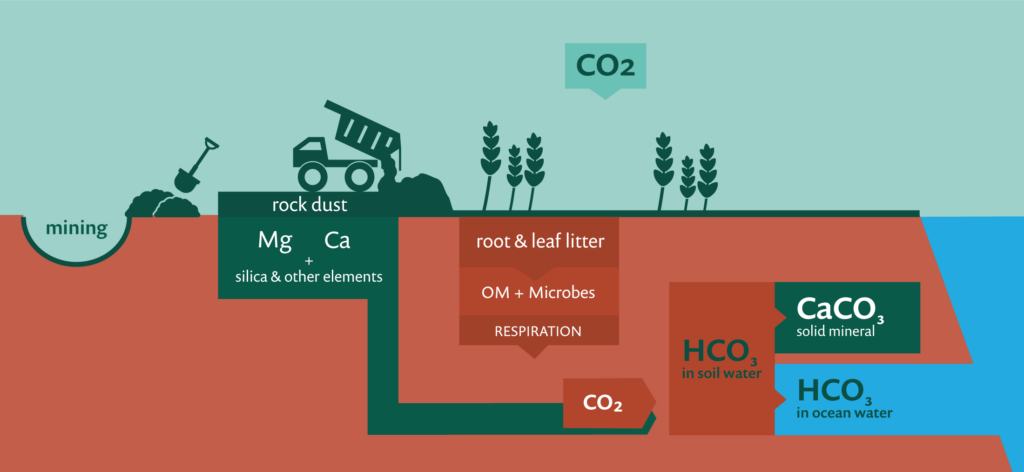

- Enhanced rock weathering (ERW), an emerging technology that permanently draws down carbon from the atmosphere and has the potential for agricultural co-benefits makes it an attractive mitigation strategy in the smallholder farmer context.

- There is evidence that conservation agriculture practices that many farmers are already familiar with – such as reduced tillage, the use of cover crops, and intercropping – promote the sequestration of organic carbon in soils.

- In terms of nitrous oxide emissions, simple decision support tools following the Site Specific Nutrient Management approach, i.e. Leaf Color Charts (LCC), have been shown to reduce nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use as well as improve farmer outcomes.

- For methane, improving feeding practices that increase milk production and closing the dairy yield gap in the Global South per cow can lower the methane intensity of production and contribute to methane mitigation, as well as improving farmer livelihoods.

We’re excited to be on the cutting edge of exploring the potential of these climate change mitigation opportunities- like scoping a digital version of Leaf Color Charts to enable the tool to reach a wider scale and Advanced Market Commitments to incentivize R&D for enhanced rock weathering. Our research initiative with IGSD has enabled PxD to identify future activities within each opportunity area to advance climate change mitigation in the smallholder farmer context and we are actively pursuing partnership and funding opportunities to advance these activities.

Learning to leverage research partnerships for scalability

Partnerships have proven to be a critical pathway to increasing impact and scaling evidence-based programs across our project portfolio.

By collaboratively identifying and developing high-impact opportunities with dairy cooperatives in Kenya, PxD has identified a new partnership model in which PxD serves as a technical and analytical partner for innovating and testing service offerings for cooperatives, and builds cooperatives’ capabilities for generating greater impact at scale. We kicked off the partnerships with Lessos Dairy and Sirikwa Dairy by adapting an asset-collateralized loan product for water tanks which has been shown to dramatically increase access to water tanks among dairy farmers in a research study (Jack et al, 2022) and setting up an evaluation to measure its impact on economic and household outcomes.

In Gujarat, India we surmise that identifying low-cost and scalable approaches to crowdsource pest information will require leveraging local organizations and existing social networks for cost-efficient recruitment and training of agents.

To further explore opportunities to support women farmers in Gujarat, we successfully established partnerships that allow us to better understand the constraints women farmers face in engaging in economic activities and their access to information and other services. These partnerships allow us to design and implement group-based digital services to address those specific constraints.

Insights to shift and refine our approach

Our scoping activities allowed us to identify when a change in approach was needed or when interventions did not turn out to be as promising as we had hoped.

In the dairy sector in Kenya, we learned that existing market and coordination failures, such as credit constraints, need to be addressed to create an environment in which digital advisory can effectively improve smallholder dairy productivity.

In testing social learning mechanisms in Kenya, we did not find evidence that the designed intervention increased farmers’ knowledge or the likelihood of adopting recommended practices, despite finding that peer learning was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members.

While subsequent qualitative interviews suggest that some farmers visited the farm fields of their peers and experimented with the recommended practices in a small portion of their plot, developing the digital peer group advisory further is likely to require a substantial investment in basic research to understand farmers’ social learning process and identify creative ways to reduce the relatively high costs associated with forming peer groups.

Finally, we learned to exercise caution in working with established women’s groups in Gujarat in a way that does not exacerbate local power dynamics within communities to ensure PxD’s services are designed in a sensitive way to promote the inclusion of marginalized groups that may face particularly challenging digital access gaps.

Looking forward to continue building our evidence base

In the coming year we are looking forward to continuing to build our evidence base with forthcoming insights on PxD’s impact on farmer welfare from several large-scale RCTs in India, Uganda, and Kenya.

For the impact evaluation of our largest service offered to date for rice farmers in India, endline data collection and analysis are expected following the second season of implementation in 2023. In addition to outcome data on farmers yields and profits, we’re excited to generate additional insights on scalable measurement options for detecting yield changes among rice farmers using remote sensing data.

In Uganda, our work with coffee farmers enabled PxD to explore several dimensions of digital advisory, including comparing a stand-alone digital advisory service to the provision of digital advisory as a complement to in-person training and studying social spillovers from our advisory services. An endline analysis of the effects of this program will be forthcoming in 2023.

We are also excited to generate initial insights on the impact of asset-collateralized loans for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. Using frequent administrative data from dairy cooperatives on milk production, we’ll be able to understand how improved access to water tanks helps farmers mitigate productivity shocks and domestic water shortages as farmers adapt to more dry spells from a changing climate.

In addition to evaluation research with rigorous RCTs, we look forward to building out our research innovation agenda in the coming year. We are exploring a variety of new, evidence-based high-value product innovations that can build on our agricultural impact for smallholder farmers, such as interventions to facilitate market linkages and access complementary financial services. We are committed to using rigorous evidence and deep user research to identify and prioritize which ideas to pursue.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2023! If you’d like to learn more or partner with PxD on specific areas highlighted please get in touch!

Punjab means “five rivers”, and those five rivers are the reason that the Punjab region in Pakistan is the country’s bread basket. Tomoko and I were in Punjab last week visiting the PxD Pakistan country team. As many of you will know, PxD in Pakistan is housed within a local economics research institute, CERP, a partnership that has enabled us to be more effective and flexible.

This week much of our attention has been on smallholder rice production. The staple food in Pakistan is of course wheat (for roti), but rice is a major crop for both domestic consumption and export. (We were in town at the same time as the IMF delegation, negotiating a package of macroeconomic reforms to stabilise the economy, so those export earnings are important right now).

Punjab is famous for its basmati rice, a variety much prized for its aroma, fluffiness and grain length. It is very popular in traditional dishes like biryani and pulau. We visited Kala Shah Kaku Rice Research Institute, established in 1926, where basmati rice varieties have been developed since the 1930s. Farmers in Pakistan typically grow wheat in the Rabi season and then many grow rice in the Kharif season, especially in the basmati belt in Punjab. The yield of basmati rice is around half as much per hectare as hybrid rice varieties, but it sells for around twice the price, so generating similar revenues and broadly similar net income per hectare. (An exciting development on the horizon is the prospect of hybrid basmati rice that may have a much higher yield while retaining much of the quality for which basmati rice is famous.)

Many of the people we met were keen to stress that Pakistan, rather than India, is the home of basmati rice. I’d be very glad if the rivalry between these two great nations were confined to arguing about the origin of basmati rice and, far more importantly, their relative prowess in cricket.

Pakistan’s farmers produce on average around 4 tonnes of rice per hectare, about the same as in India. In China, the yield is 7 tonnes per hectare and in Australia 10 tonnes per hectare. The yield gap (that is, the gap between what farmers produce and what they could produce with the land and other inputs available to them) is estimated to be about 50% – about 3.5 tonnes per hectare – for basmati rice, and closer to 60% – 6 tonnes per hectare – for the higher yield but lower price varieties. In other words, farmers could, in principle, at least double their yields. So what is holding them back?

You would expect farmers to be more interested in increasing their profit than their yield, so one possible explanation – in theory – could be that the additional inputs are too costly, and the value of the extra output does not justify the investment. In that case, it would be rational for farmers not to increase their output this way. But that doesn’t seem to be the problem. The additional cost of the recommended inputs, at market prices, is small relative to the price that basmati farmers could get for the roughly extra 3-4 tonnes per hectare that they could be producing. Despite extra input costs, the extra yield on this scale would lead to much higher profits – perhaps multiples of profits now being earned. If you are doing only a little better than breaking even, then moving to a reasonable surplus could mean a transformational increase in net income.

So what is getting in the way? We spent two days in villages outside Lahore talking to farmers, extension agents, and private and public sector experts to try to get a better picture.

My main take-away is that it seems that expensive credit for agricultural inputs and low prices paid by middlemen (called aahrtis) leaves farmers with little surplus. Farmers are unwilling to take on a large, expensive debt which – if the harvest is bad – they may not be able to repay, especially when they know that a big chunk of any profit, if the harvest is good, will go to the middleman. So they stick to limited use of inputs, which gives them lower yields and less debt and thus lower risk. Thus it is the cost of credit, and the associated risk, rather than the cost of the inputs themselves, that stops them from investing more.

I’m conscious that we met farmers close to Lahore, who are relatively well-off, and who are already in contact with extension services. So we should be careful about drawing too many conclusions. Based on these few conversations with an atypical group of farmers, I find it hard to convince myself that there are very many practices that farmers could adopt that they do not already know about. That said, there may be some value to encouraging practices that cost the farmer little or nothing to implement – or which save inputs such as using the right amount of urea – for example by issuing timely reminders. But it looks as if the larger gains would come if we could find a way to reduce the risk of increased investment in inputs, reduce the cost of credit, provide high-resolution weather information, or perhaps improve planning and coordination in the use of scarce machinery or casual labour.

It is harder to notice what is missing than what is in front of you. As you may see from the photos, we did not meet any women farmers. We met a female scientist at the rice institute, but everyone else we spoke to was a man. In every conversation, farmers were routinely and unthinkingly referred to as “he”. Yet we know that women provide a substantial part of labour in agriculture, and are hugely affected by all the decisions that are made. If we want to understand what it would take for farmers to adopt practices that would increase their yield and their incomes, we are likely to learn a lot by talking to women too.

I leave Pakistan optimistic but uncertain. Optimistic because the opportunities are huge for large increases in yield and potentially transformative increases in farmer incomes. The constraints are real, but there may be solutions that have a low marginal cost per farmer and so would be hugely cost-effective at scale. Uncertain because we do not yet have enough information to arrive at robust ideas for higher-impact services that we could design and test.

I want to thank Adeel, and all the team, for giving up so much of their time and energy to host us – including taking us to the old Walled City of Lahore to have dinner overlooking the famous Badshahi Mosque (Mosque of Kings) and the Lahore Fort (Shahi Qila in Urdu), an ancient citadel of the Mughal Empire. I look forward to returning to Pakistan soon and hope to combine my next trip with some tourism in your beautiful country.

When disease and a heatwave, followed by devastating floods ravaged Pakistan’s Punjab province, PxD’s LMAFRP digital information service, which we implement in partnership with the Rural Community Development Society (RCDS) with support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), assisted women livestock farmers navigate new and unprecedented challenges. This International Day of Rural Women, we highlight the important role women play in Punjab’s rural farming economy and our work to promote information to enhance more productive and resilient livelihoods.

Introduction

Livestock husbandry and livestock-related products (dairy, meat, leather goods, etc.) constitute an important sub-sector of Pakistan’s agriculture sector: Pakistan is the fourth largest milk-producing country in the world1Sattar, Abdul, “Milk Production in Pakistan” PIDE Blog, pide.org.pk/blog/milk-production-in-pakistan , and the share of livestock products in the generation of foreign exchange is approximately 13%2Government of the Punjab, “Livestock Contribution” , livestock.punjab.gov.pk/livestock-contribution. As is the case in many smallholder economies, in Pakistan, women are largely responsible for the care of livestock and for the production of many livestock-related products, particularly dairy3Ibid..

In rural areas, livestock plays an outsize role in livelihoods, with the Punjab provincial government estimating that “livestock is an integral part (30-40%) of the livelihood of about 30 to 35 million rural farmers”4Ibid.. Livestock-related products, such as butter, eggs, meat, and animal fats (oils), contribute important nutrients for all households – rural and urban – and play a critical role in meeting the nutritional needs of rural children. Further, livestock contribute an important source of continuous income which can sustain poor rural households between seasonal crop-related revenues, and insulate them from shocks5Ahmad, Tusawar Iftikhar and Tanwir, Farooq, “Factors Affecting Women’s Participation in Livestock Management Activities: A Case of Punjab-Pakistan”, mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93312/1/MPRA_paper_93312.pdf..

For these reasons and more, supporting the development and improvement of livestock farming can have a considerable impact on improving the livelihoods of Pakistan’s rural population, and can impact the livelihoods and status of rural women. We believe significant gains can accrue to rural farming families through the promotion of best practices to women. Improved practices can improve yields and minimize losses, leading to increases in income from livestock farming.

Many rural women are unaware of best practices that can optimize outputs associated with livestock, and access to information and economic opportunities can be constrained by cultural and geographic barriers. As documented elsewhere on this blog, digital extension services offer cost-effective and easily scalable solutions with very low marginal costs. In rural Pakistan, where many women rarely leave their homesteads, the portability of digital information offers additional advantages for navigating geographically and culturally hard-to-reach spaces.

Geographic and cultural constraints to attending in-person RCDS livestock training sessions were exacerbated by social distancing introduced to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. RCDS’s in-person activities were suspended in the initial months of the pandemic, but the utility of advisory information increased as rural households navigated new challenges in a time of escalated economic stress. It was at this time that RCDS and PxD initiated a partnership to deliver advice to livestock-rearing women in rural regions of Punjab province in Pakistan. This collaboration, supported by IFAD, provides customized and actionable digital information to livestock-rearing women. Combining PxD’s experience in delivering digital extension services to Punjabi farmers and RCDS’s extensive local knowledge and expertise, the service draws on demographic insights, and cultural practices to deliver information that is accessible, comprehensible, and actionable for recipients.

The resultant digital advisory service has proven to be an effective, cost-efficient, and scalable supplement to in-person training, and is now extended in the absence of COVID-19-related social-distancing constraints. The service demonstrated new advantages when unfamiliar disease- and climate-related threats subsequently impacted rural households.

The Service

RCDS’s experience and local trust in their services have been integral to the success of the initiative. Over the past two decades, RCDS has partnered with local, federal, and international institutions to build a significant rural network to promote and implement development programs to assist poverty-stricken segments of society in rural areas of Pakistan.

Advisory content was developed in partnership with local livestock consultants who were well-informed about local livestock issues and output-increasing best practices. The advisory information distributed by the service covers a wide array of topics, including disease identification, information about and access to vaccinations, disease prevention and remedies, practices to increase milk yields, and guidance on protecting livestock against climate-related shocks.

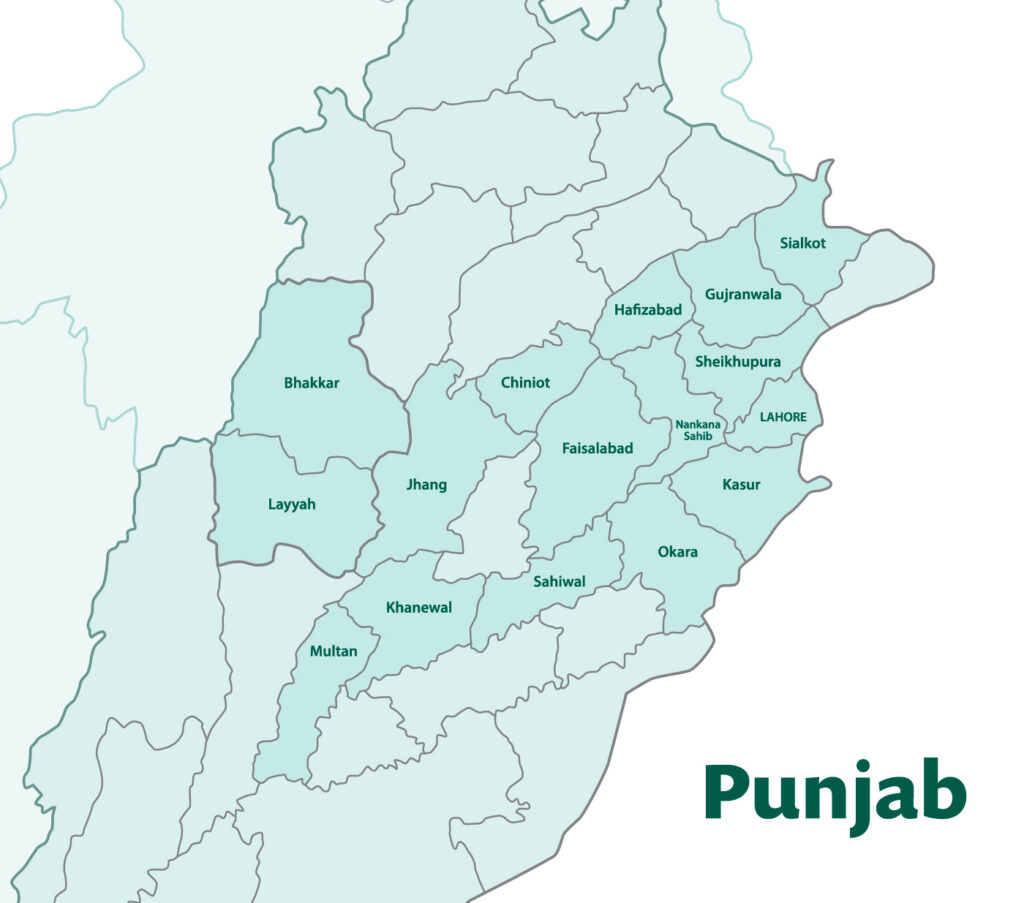

After conducting a baseline survey to systematically understand the informational needs of women farmers in four districts in Punjab, and the development of advisory information, PxD piloted digital services among 3,160 rural women associated with RCDS. The four districts, in which the pilot was concentrated, are among the poorest districts of Punjab, all of which are located in the south of the province. Given the success of the initial pilot, the service has subsequently been expanded to more than 50,000 livestock-rearing women in 16 rural districts of Punjab.

One of the key components that PxD assessed during the initiative was the extent of knowledge retention by participating women after they received the advisory. Pilot testing in the early stages showed that the advisory information was not only useful but was also retained for a significant period after it was delivered.

RCDS maintains a dataset of women who have either attended in-person sessions of livestock advisory or shown an interest in livestock advisory or have taken a microfinance loan for livestock farming. This data, and its quality, were instrumental in helping PxD deliver the advisory directly to the women via their phones. Furthermore, the data also contained the districts in which each woman resided. This was used to help decide in which of the two local languages – Punjabi and Saraiki – the advisory would be conveyed.

Advisory information is delivered through a voice call. A text message is sent 24 hours before the call to alert users that they should expect a call the next day. This is done to ensure that the advisory is received by women. A barrier highlighted by the baseline survey was limited access to mobile phones on the part of women in the region. Cultural and financial constraints make it far more likely that men have primary access to cell phones. Hence, the time allotted for the voice calls is set at a specific hour in the evening, so that the call is received in the evening when the family is no longer busy with agricultural activities, men are more likely to be home, and when family members can collectively listen to the advisory in their homes.

The voice call has local cultural music layered in the background, to assist the participant in developing trust in and comfort with the message. The information is delivered in the local dialect – Punjabi or Saraiki – to enhance understanding of and familiarity with the recorded message. Further, listeners are told that the advisory is from RCDS since it is well-known as a trusted organization in these regions. As a general protocol, to improve pick-up rates when the voice call is unanswered, another call is placed after a 15 to 30-minute interval.

Lumpy Skin Disease

A significant advantage of digital extension is the ability to send timeous information. This is particularly valuable to address and prevent viral diseases that can have a drastically negative impact on the well-being of the livestock.

In April 2022, Pakistan saw a viral outbreak of lumpy skin disease in cattle. The disease was transmitted between cattle via blood-feeding insects. The disease has a high virulence and fatality rate and killed thousands of cattle in the country.

A significant hurdle that seriously hindered timely prevention and actions to curtail the impacts of the infestation was the lack of baseline knowledge and awareness of the disease. Moreover, misinformation was rife, with misplaced rumors about negative effects of vaccines abounding. Many people mistakenly believed that it was the vaccines that were causing deaths among animals, when animals that had died were either already infected with lumpy skin disease, or were generally sick and should not have been vaccinated at the time.

Understanding these knowledge gaps, PxD and RCDS collaborated to provide timely information about the infestation. Initial infections were observed in the southern part of the country and slowly spread north towards Punjab province, where our users reside. PxD started providing information about lumpy skin before the disease had become widespread in the province.

Our farmer-users were given information about the disease and its virulence, how it is spread, and traditional preventative measures. Following that, to increase the survival rate of infected cattle, users of the service were advised to vaccinate their cattle as soon as vaccines became available. Participants were also informed about how to identify early signs of the disease on the animal.

Anecdotal feedback received by RCDS in the field suggests that the messages were very useful. Users with whom PxD surveyed reported that in many instances they were able to avoid fatal infections in their animals due to timely vaccines, even if their animals did get infected.

The Floods

In the summer of 2022, Pakistan witnessed firsthand the severe impacts of climate change. In March and April, the country experienced a crippling heat wave, followed by a record-breaking monsoon season in Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan spanning June, July, and August. An unparalleled monsoon, coupled with unprecedented melting of glaciers in the north due to the initial heatwave, led to extreme flooding in rivers that flow from the north of Pakistan to the south. The floods are estimated to have impacted at least one-third of Pakistan, including the livelihoods of 33 million people.

Prior to the floods, the extreme heat waves had contributed to a general belief that floods were imminent. To counter the threat, the PxD team in Pakistan worked with RCDS to preemptively identify areas prone to flooding, and prepare advisory messages with useful information about managing floods, and adaptive strategies to protect assets and livelihoods.

A major problem with livestock is their slow mobilization, making them and their rearers prone to becoming flood victims. Timely warnings and regular updates via voice call advisory messages provided participants with information for ensuring the safety of their livestock during the floods. PxD and RCDS made use of their existing program to deliver instructions, warnings, measures, and assistance via voice call messages, to inform participating women and their families about floods and ways to protect themselves and their livestock.

Meeting today’s challenges

The advisory service designed by PxD, and delivered in partnership with RCDS, provided an effective method to deliver timely information to livestock farmers. Due to its effectiveness in the regions where it was being delivered, the advisory service was extended to address other unforeseen challenges, such as the virulent lumpy skin disease, and flooding.

In addition, our project has demonstrated the core strengths of digital communication: it is cost-effective, scalable, and capable of reaching regions and communities that are disconnected or hard to access due to difficult terrain, long distances, or cultural constraints.

Our advisory content was designed to deliver information in a manner that does not require the recipient to have prior knowledge, or education to understand the subject. The use of familiar dialects and carefully crafted messages made the information accessible, easy to understand, and ultimately very effective.

PxD aims to further extend the benefits of digital communication to support other low-cost interventions among rural communities of Pakistan. More specifically, feedback received from users has prompted PxD to further our partnership with RCDS to envisage interventions to support digital veterinary services. We are motivated to continue to harness the power of digital communication to facilitate more productive and resilient livelihoods in rural communities of Pakistan.

Given existing poverty, dependence on agriculture for livelihoods, and lack of access to safety nets, poor smallholder families in low- and middle-income countries are particularly vulnerable to exogenous shocks. In March 2020, when the world shut down and told people to stay home to mitigate the public health impacts of COVID-19, many poor smallholder families were left reeling. In response to the growing humanitarian crisis, in April 2020 the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) launched a multi-donor COVID-19 Rural Poor Stimulus Facility (RPSF) to improve food security and resilience among poor rural people during the pandemic.

PxD was one of several RPSF grant recipients and interventions selected, all of which focused on either digital services, providing inputs or assets, access to markets, or targeting funds for rural financial services. In collaboration with the IFAD country teams and their government partners, PxD implemented three digital advisory services in Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan between August 2020 and September 2021 to provide digital extension services to approximately two million users. PxD reached 1.2 million farmers in Pakistan, 650,000 in Kenya, and 100,000 in Nigeria, surpassing the initiative’s target of 1.7 million farmers. This includes roughly 178,000 IFAD project beneficiaries across the three countries. These farmers received timely, relevant, and customized agricultural recommendations to improve their farm productivity directly via their mobile phones.

After successfully launching the initial digital services and delivering agricultural advice, IFAD and PxD conducted RPSF rapid assessments in late 2021 to assess farmer outcomes in all three countries. The surveys were designed to compare production, sales, income, food security, and resilience outcomes after the onset of COVID-19 but before the digital advisory intervention (the pre-intervention period) and after the intervention (the post-intervention period). We define resilience as the ability to cope with unexpected challenges and shocks, such as the ability to deal with drought/floods, pest invasions, and rising input prices. The final sample sizes for Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan were 400, 395, and 600, respectively. We stratified the samples by gender, youth status.Youth was defined as heads of households under 35, agro-ecological zone (AEZ) or state1Agro-ecological zones were used in Kenya and Pakistan; the survey covered seven (including unknown) and five AEZs, respectively. We stratified by seven states in Nigeria., and engagement level Kenya and Nigeria only, where we differentiate between high and low engaged users using the median number of messages or calls responded to. so we could analyze and compare outcomes by these subgroups. Within a country, we tested for statistical significance of crop, livestock, poultry, and agribusiness production and sales, as well as food security and income indicators between the pre-intervention and post-intervention period. The samples of farmers selected for the intervention and the surveys were randomly selected from our user bases of IFAD beneficiaries within each country, which may not be nationally representative. Moreover, this is a descriptive analysis, and we cannot infer whether PxD’s services had a causal impact on outcomes reported after the intervention because of the lack of an experimental design (there was no control group).

Farmer-reported outcomes during COVID-19, pre-intervention

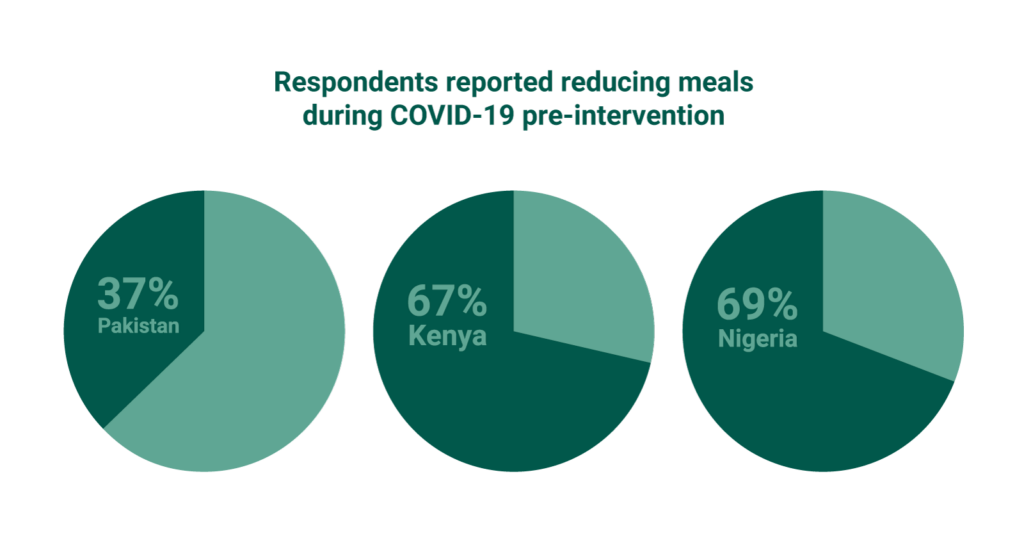

Across all three countries, most respondents reported a loss or reduction in production, sales, number of meals, and resiliency during COVID-19 prior to PxD’s RPSF intervention (pre-intervention period). Respondents from Pakistan seemed to be the least affected by the onset of COVID-19, as fewer respondents reported reductions or losses, compared to Nigeria or Kenya. Moreover, almost half as many respondents reported reducing meals (37%) than in Kenya (67%) or Nigeria (69%). For all indicators except food security, respondents from Kenya reported the worst outcomes, including over 98% who reported lost or reduced production during COVID-19. There was also a wide disparity between the percentage of respondents reporting selling assets across the three countries. Almost two-thirds (65%) of respondents in Kenya reported selling assets because of COVID-19, whereas less than 10% of respondents in Nigeria reported the same.

We also disaggregated production and sales outcomes by specific types of farming that farmers engage in, namely: crop growing, livestock rearing, poultry raising, and agribusiness activities. We find that agribusiness production and sales suffered the most in Pakistan when compared to crop, livestock, and poultry. This finding could be attributed to COVID-19 restrictions which limited the ability to engage in business activities. However, in Kenya and Nigeria, farmers reported larger reductions in crop production and sales compared to livestock, poultry, or agribusiness.

While respondents in Kenya overall seemed to fare the worst in the pre-intervention period, Kenyan women suffered disproportionately more. For example, all Kenyan women reported a reduction or loss of production during the pandemic, and women reported higher reductions than men for all other indicators. We don’t see the same clear pattern in Nigeria or Pakistan, although more women from all three countries reported worse food security outcomes than men. This could in part be due to cultural expectations of women eating last and in small portions, compared to men in the same household.

… and post-intervention

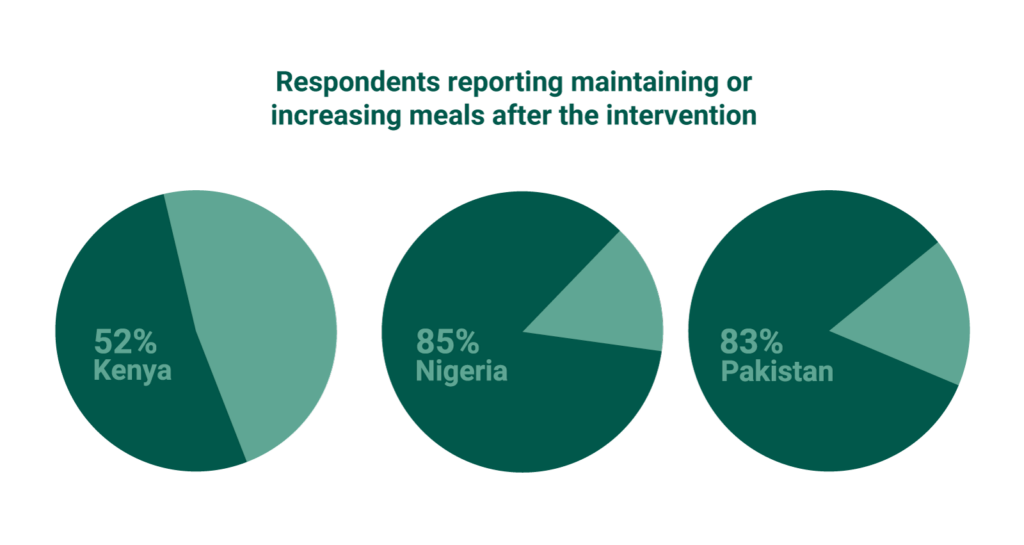

After the RPSF intervention concluded in late 2021, during a lull in the COVID-19 pandemic between the Delta and Omicron waves, we observed encouraging evidence of improved farmer resilience. Respondents in all three countries indicated that conditions had improved relative to the early phase of the pandemic, at the onset of COVID-19 but before the digital advisory intervention (the pre-intervention period), however, some fared better than others. For example, Nigerian respondents reported maintaining or improving production, sales, income, meals eaten, resilience, and asset indicators at higher rates than those in Kenya and Pakistan. Considering the poor conditions they reported during COVID-19, we take this as a sign that Nigerian respondents may have recovered from the pandemic more quickly than their counterparts in Kenya and Pakistan. Conversely, in addition to suffering the worst outcomes in the pre-intervention period, Kenyan respondents indicated that they maintained or improved outcomes the least in the post-intervention period. Only about half of Kenyan respondents reported production and meals were maintained or increased, and less than half reported maintaining or increasing sales, income, resiliency, and assets. Only 25.5% of Kenyan respondents reported income stayed the same or improved, highlighting that Kenyan farmers have struggled significantly in recovering from the pandemic, even after receiving the intervention.

Kenya experienced severe drought during the long rains 2021 season (February-March to June-August depending on location) while the RPSF intervention was underway and during the collection of this data, which likely contributed to the poor outcomes reported after the RPSF intervention. For example, many farmers reported failed crops rendering it impossible to follow the customized digital advisory of the intervention, and to harvest and sell their crop. This is corroborated by reports estimating reduced crop production of up to 70% in Kenya during the drought2Oxfam International, 2022 https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/many-28-million-people-across-east-africa-risk-extreme-hunger-if-rains-fail-again.

Disaggregating the results by type of farming activity, we find that Kenyan and Pakistani farmers reported production and sales reductions in agribusiness the most, even after the RPSF intervention. Because COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the government persisted during the intervention and survey period, we suspect that these restrictions played a role in farmers’ ability to engage in agribusiness, resulting in lower production and sales than other farm activities. In Nigeria in the post-intervention period, farmers reported reductions in production and sales for crop farming more than the other surveyed farm activities, suggesting that even though there were improvements to production and sales after the intervention, farmers’ crop yields suffered the most, relative to their livestock, poultry, and agribusiness activities.

In Pakistan, we observe better outcomes than in Kenya, although slightly less than half (48%) of respondents indicated they maintained or improved their income after RPSF, and only slightly more than half (57%) reported maintaining or improving their sales. Greater than expected wheat yields might have contributed to the better outcomes observed in Pakistan. But while these figures are somewhat encouraging and indicate that some Pakistani farmers were able to recover from COVID-19-related shocks, it also indicates that a significant share of farmers has not recovered. This could be because of the lingering effects of COVID-19 such as global trade shocks and new variants disrupting economic activity via additional lockdowns.

Similar to the outcomes reported during COVID-19, Kenyan women respondents indicated they maintained or improved outcomes less than their male counterparts after the intervention, across all indicators except assets. Only 17.3% of women reported maintaining or improving their income after RPSF, which is almost half the proportion for men, highlighting the predicament of women in Kenya in the face of COVID-19 and drought-related shocks. In Pakistan, while overall outcomes were better, we still note women reported maintaining or improving production, sales, income, and meals at lower rates than men. In Nigeria, a higher proportion of women actually reported maintaining or improving income, meals, and resiliency, and for the other indicators, women reported maintaining and improving at similar rates to Nigerian men. However, we also found evidence that women were disproportionately affected in the livestock sector; Nigerian women were more likely to report reductions in livestock production and sales after RPSF, compared to their male counterparts. Across all three countries, women reported faring worse than men in maintaining or increasing sales.

We also disaggregated the post-intervention RPSF results by farmers’ level of engagement with the PxD service, where we defined highly engaged users as having picked up or responded to more than the median number of calls (Nigeria) or SMS messages (Kenya)3We did not disaggregate by level of engagement in Pakistan.. In Kenya, we did not see any clear patterns by engagement level. However, in Nigeria, we found that highly engaged users (who picked up more than seven calls) reported maintaining or improving production, sales, and income at a higher rate than lower engaged users. This result provides suggestive evidence to our theory of change that users who more actively engage with our services may implement more of (or implement better) our recommendations, leading to improved outcomes.

It was challenging to draw clear conclusions from the data at the level of agro-ecological zone and state, due to the small number of respondents per zone or state. For example, in Kenya, there is some evidence that households from the upper highlands (UH) AEZ fared better than respondents in other zones. This may be because the UH zone was less affected by severe drought than other more arid regions in the country. In Nigeria, respondents in Katsina fared worse than the other states, reporting the highest level of reductions in most production, sales, food security, and resiliency measures. We suspect that local terrorism and banditry in the state played a role in the poor outcomes reported there. Meanwhile, respondents in the Nigerian state of Jigawa reported faring the best, which may be because widespread telecommunication shutdowns that plagued the country during the grant period were avoided, and the state is relatively peaceful compared to others in the north.

While the initial COVID-19 shock occurred in early 2020, the results of the surveys suggest that there are strong lingering negative effects in all three countries (as well as other severe shocks such as extreme weather events and terrorism) and more direct support is needed to return smallholder farmers to their pre-COVID-19 state. While this analysis does not estimate the causal impact of PxD services, we plan to use the data from this analysis to improve our services to more effectively meet farmers’ needs. In Kenya, we hope to specifically address weather-related shocks such as severe drought. Weather-related services are already being explored in Pakistan and India and learnings from these pilots might also be applicable in Kenya. Based on the evidence that women found it more difficult to cope and recover from COVID-19, we hope to develop women-targeted interventions designed to reach more women users or develop content tailored to women’s needs. This will build on gender-focused service experimentation we have undertaken such as providing messages with a female narrator and nudges encouraging spouses to share PxD advisory with each other, as well as implementation of advisories focused on female-dominated value chains such as kitchen gardens, dairy, and livestock.

Since the conclusion of the intervention and endline survey, farmers’ situations have become even direr. Experts warn of rising food shortages and hunger due to high global inflation and supply chain disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine. The World Bank estimates that the Agricultural Price Index is 14% higher as of this June compared to January and 94% of low-income countries are experiencing food price inflation greater than 5%. The already looming food crisis is expected to be exacerbated by a sharp increase in fertilizer prices, largely driven by the war in Ukraine, as Russia and its ally Belarus produce 40% of the world’s supply of potash, and Russia and Ukraine together export 28% of nitrogen and phosphorus-based fertilizers. Within this context and amid the backdrop of the ongoing pandemic, the need for strong support for poor smallholder families is urgent.

Our partner and funder, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), has published a ‘story’ on their website about our collaboration to deliver much-needed digital information to Pakistani smallholder farming families to promote resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We look forward to deepening our engagement with IFAD in the service of smallholder farmers in Pakistan, and beyond!

Read more about the initiatives we have implemented in partnership with IFAD :

PxD is building a free weather forecast product for cotton farmers in Pakistan’s Punjab Province to be launched in March, ahead of Kharif – South Asia’s summer planting season. The service will be launched in phases and will ultimately serve 490,000 smallholder cotton farmers across the province.

We are excited by the pioneering potential of this product for distributing weather information to inform decision-making on the part of poor, rural farmers in Pakistan’s cotton belt. Moreover, we have been excited to engage in an intentional process of product design from which we have learned a great deal, and which we anticipate will inform the further iteration and development of weather programming and forecast provision across PxD’s geographies, and beyond.

As we have iterated this new product, we have grappled with wide-ranging design possibilities that could increase usefulness and impact. Guiding questions include: Is it more valuable for farmers to receive good weather information – as is typically offered – or is it more valuable to complement forecast information with digital agronomic recommendations (a core PxD competence)? During what stages of the crop cycle, and for which key decision-points, is weather advisory most valued and impactful? At what frequency should advisory be given? How does one communicate probabilities in a way that is accessible and practical for farmers? How does a farmers’ relationship with the weather – and informational needs – differ based on whether their crops are irrigated or rain-fed?

To guide more informed product design decisions, in November the Pakistan team commenced with a set of end-user interviews with 55 cotton and wheat farmers. While 71% of wheat farmers cited access to weather forecasting information, only 45% of cotton farmers surveyed reported access to weather information. When asked if weather information “helped in planning”, 88 and 86% of cotton and wheat respondents respectively responded in the affirmative. This finding buttresses an earlier survey of wheat farmers users in Pakistan where, in response to the question “What agriculture-related information do you need for your wheat crop during the next month?”, 18.5% of respondents cited weather. When canvassing end-users in November, farmer users were asked to “Please list the types of weather challenges you have experienced” in the three years prior to being surveyed. Forty-three percent of respondents who reported experiencing weather-related challenges cited heavy rainfall and 30% reported high winds.

These types of weather incidents can be very costly for smallholder farmers with limited resources. Inundation washes away expensive inputs, creates mud that blocks sprouting crops, and creates conditions conducive to disease, while wind can destroy or severely damage crops throughout the cropping cycle. Further, when prompted to answer “Out of these weather challenges, which three have the largest impact on your crop costs and yields”, pest management was reported as the most common answer. Many pests and diseases thrive in particular weather conditions and can proliferate quickly if conditions are optimal. This suggests that a combination of advisory and weather forecasting information alerting farmers to be on the lookout for pests and to initiate pesticide application decisions sooner could be valuable as a means for reducing pest damage.

To test certain features of our Kharif forecasting products in practice, the PxD Pakistan team took advantage of the ongoing Rabi wheat season (winter planting cycle) to launch two minimum viable products (MVPs) as an AB test. This round of product development was delivered to roughly 2,000 wheat farmers, with each pilot product servicing approximately 1,000 farmers, respectively. The first treatment entailed a simple 48-hour weather-only forecast delivered via SMS and robocall. The second treatment issued an equivalent 48-hour weather forecast to 1,500 wheat farmers, complemented by recommendations on how to adjust one’s irrigation accordingly.

In February, when users have been exposed to the MVP services for two months, they will be surveyed to obtain richer feedback. This survey will aim to answer the fundamental question about whether farmers value weather-linked advisory over weather-only messages. If weather-only is the clear preference, this may suggest that farmers are generally able to connect actions to relevant weather. In the event that farmers do not explicitly need advisory as a complement to forecasting information, this would greatly simplify product development. Secondary questions source farmers’ views on the frequency and relevance of distributed messages. Lastly, under the hypothesis that farmers will prefer advisory linked to weather information, in-field focus groups will be conducted in March to expose farmers to an array of pre-recorded agronomic recommendations and message framings. Feedback from farmers will be used to inform the iteration of advisory scripts and message framing as we work to maximize comprehension, particularly relating to the communication of uncertainties and probabilities, and address potential barriers to adoption.

Another core challenge in developing this product is the quality of the weather forecasts themselves. The existing forecast services in Punjab tend not to be designed with the end user’s needs in mind. Three services in Punjab, Pakistan exemplify usability issues: the first requires user-initiated, user-paid inbound calls; the second requires internet access; and the third is only available to subscribers of a particular telecoms company.

To overcome these types of challenges, PxD is partnering with the private forecast provider CFAN (Climate Forecast Applications Network) to develop calibrated custom forecasts. CFAN is a leading forecast provider, with temperature, cyclone, and severe weather products across North America, Central America, and Asia, and extensive experience in forecasting South Asia weather dynamics. In addition to giving PxD the flexibility to adapt CFAN’s data streams according to our users’ needs, we are using this partnership to transparently assess the magnitude of upfront costs required to build a forecast system.

Learnings from these research activities, coupled with insights generated by our collaboration with CFAN, will inform the final design of our Kharif weather forecasting product for cotton farmers. Once this product is up and running, the focus will shift to impact evaluation, including pick-up rates, behavior changes, and forecast accuracy. Pending a review of such impact outcomes, and funding considerations, the product will be further developed to cover the Rabi season and potentially scaled to additional countries.

This Kharif season, we are thrilled at the prospect of hundreds of thousands of Punjabi smallholder cotton farmers witnessing less fertilizer – and by implication, fewer resources – washed away or harvests inundated by unexpected rains, deploying more effective irrigation tailored to the forecast, and incurring fewer crop losses due to heavy rains and winds. When we asked our PxD Pakistan agronomist about the potential impact of this product, she said: “This product will reduce farming risks and expenses, and increase what is usually a farmer’s sole source of income – allowing for more investment into farming or money for personal expenses”. We are also excited about the potential for this product to serve as a template for iterative product and design process management, and proof of concept, which others may learn from and implement in other settings.

Mark Tamming is an Associate in the London Office of Oliver Wyman, a management consulting firm. Oliver Wyman generously sponsored Mark in joining PxD as an ‘extern’ for three months on PxD’s product team. Shams Sadiq is a Research Associate on the PxD Pakistan team. We thank Khushbakht Jamal, Mahroz Haider, Jagori Chatterjee, Fatima Fida, Adeel Shafqat, Omer Qasim, Hannah Timmis, and the broader PxD Pakistan team who offered valuable contributions to this post and the product development that sits behind it.

Accurate weather forecasts would reduce uncertainty for farmers, yet they are under-supplied and under-studied in developing countries. Government and market failures reduce the quality and reach of weather information in rural regions, reducing its value for households. To address these gaps, Precision Development (PxD) is piloting the provision of improved forecasts to farmers in India and Pakistan. The pilot will investigate how farmers interpret and use weather information, including the cognitive and informational barriers that constrain adoption.

The costs of weather uncertainty

Smallholder farmers live with copious amounts of risk, leaving them vulnerable to income variability and losses. Weather uncertainty is a major source of this risk. A survey of farmers in poor, southern districts of India, for example, found that 73% of respondents had abandoned their crop at least once, in the ten years prior to being surveyed, after misjudging the onset of the monsoon; and one quarter had replanted (Giné et al., 2015). These activities are costly: the authors rank farmers by the accuracy of their monsoon predictions and show that the gross agricultural income of those in the 25th percentile is 8-9% lower than those in the 75th percentile. Other research documents how farmers respond to weather uncertainty by reducing investments in technologies or complementary inputs, which lowers their average profits (Zimmerman and Carter, 2003; Rosenzweig and Binswanger, 1993).

Because weather variability can be disastrous for poor households and is increasing with climate change, economists have dedicated much attention to products that mitigate its consequences, including index insurance and climate-resilient crop varieties. While effective in increasing farmers’ investments and profits, many of these innovations incur high distribution costs that limit their scalability (Cole & Xiong, 2017). PxD is therefore exploring an alternative solution for farmers that face increasing climate risk: accurate, phone-based weather forecasts.

Forecasts have a high potential for cost-effectiveness and scale. By reducing uncertainty over future conditions, they allow farmers to make better production decisions throughout the season. Long-range forecasts of conditions over one to three months can enable farmers to make more informed decisions about how much to invest or which crops to grow, while shorter-range products can be used to determine the best time to conduct activities like fertilizer application. These decisions have the potential to generate meaningful yield impacts; PxD’s agronomy team in India estimates that transplanting rice seedlings from the nursery to the field at the right time can generate yield increases of up to 10%, relative to transplanting too late. Moreover, the marginal cost of delivering phone-based forecasts is low relative to other products that reduce risk, meaning that the returns to their provision would increase with scale.

Currently, however, rigorous evidence on weather forecasts’ effects on farmer outcomes is sparse. Part of the reason may be the limited availability of accurate, useful forecasts in many developing countries. Producing high-quality weather predictions is costly and complex: state-of-the-art observation infrastructure, rapid data transmission systems, high-performance computing, and specialist staff are all required (Rogers et al., 2019). Cash-strapped public providers often lack this capacity, while the private sector has few incentives to serve poor consumers. As a result, the forecasts that smallholders can access are typically well behind the technology frontier.

The limited evidence base suggests that these quality shortfalls reduce forecasts’ value for farmers. For example, an observational study in India found that state-provided seasonal forecasts do increase agricultural profits, but only in the few areas where forecasts happen to be accurate (Rosenzweig and Udry, 2019). Additionally, in Ghana, preliminary results from an experimental evaluation of 48-hour, SMS-based forecasts, found effects on farmer behavior but not on profits (Fosu et al., 2018). Short lead times and a lack of complimentary advice may explain the lack of impact: a review of farmer-focused forecasts in developed countries finds that these factors reduce take-up and usefulness (Mase and Prokopy, 2014).

Unlocking the potential of weather forecasts

PxD’s new pilot aims to build the evidence on the benefits of improved forecasts for smallholders. We have partnered with the Climate Forecast Applications Network (CFAN), a private provider with expertise in developing innovative weather information tools in South Asia, to deliver hyper-local forecasts and related advisory to smallholders in India and Pakistan. CFAN’s products are anticipated to improve on existing forecasts in the region in terms of accuracy, lead times, and precision. Importantly, they can also be calibrated to predict weather phenomena that are particularly relevant for agricultural decision-making, such as prolonged dry spells suitable for fertilizer application or monsoon onset dates.

PxD’s pilot activities will test the efficacy of different intervention designs in both contexts, laying the groundwork for a large-scale randomized evaluation of weather forecasts’ effects on agricultural outcomes that we hope to implement in 2023. Some of the questions we will explore during this preliminary phase include:

- To what extent do farmers update their subjective weather expectations in response to different forecasts? What role do informational, cognitive, trust or other barriers play?

- How do farmers interpret probabilistic weather information? Do forecasts with a numeric probability of a weather event and a qualitative likelihood of the same event affect their beliefs differently?

- For which agricultural decisions could improved forecasts generate the greatest returns?

- Does improved weather information spread among farmers within and across villages?

The findings of the pilot and subsequent evaluation will have policy implications at PxD and beyond. For example, improved understanding of the returns to information products that reduce agricultural risk will inform PxD’s prioritization of new services, such as pest prediction models. The project will also seek to provide policymakers with evidence and incentives to increase funding to improve forecasts in regions that are under-served by governments and markets.

Many thanks to Sam Carter, Jonathan Faull and Yifan Powers for their excellent comments and suggestions on an earlier iteration of this post

Since August 2020, PAD has collaborated with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), a UN affiliated multilateral agency, to deliver digital advisory to assist smallholder farmers in Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan to boost productivity and resiliency as they navigate the evolving impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 05 May 2021, IFAD convened an #IFADinnovationtalk webinar to showcase our partnership under the auspices of presentations and a panel discussion entitled ‘Digital Agriculture and the Rural Poor: Challenges and opportunities in delivering results’. Keynote speeches were delivered by Michael Kremer, PAD co-founder and Nobel Prize winner, and Owen Barder, PAD CEO. Our colleague Uzoamaka Ugochukwu, Nigeria Country Launch Manager, participated in a panel with Vivian Hoffman (a PAD research partner at IFPRI) and Dr. Zahoor-ul-Hassan (a key champion of our work in the Government of Punjab, Pakistan), and Patrick Habamenshi (country manager of IFAD Nigeria).

As Owen Barder, PAD’s CEO, stated in his keynote address, our collaboration with IFAD has demonstrated:

First, that our services can be replicated, adapted and scaled in new geographies, and can be scaled up to new target populations in existing geographies;

Second, that we have been able to develop and deploy surveys and A/B tests to quickly and accurately gather and analyze information from users to improve our services and adapt to evolving challenges in near real time; and

Third, the combined capabilities of governments, multilateral organizations and non-profit service delivery organizations can deploy services quickly and at scale, using local talent and shared knowledge and systems.

The full text of Michael Kremer’s contribution is accessible here; Owen Barder’s speech can be accessed here; and a full recording of their presentations, panel discussion and subsequent Q&A is accessible via the video posted at the top of this page.

We envisage this our partnership with IFAD as both a mechanism for recovery from the devastating effects that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on smallholder farmers, and an investment in better ways of delivering agricultural information in the long term.

We are excited at our progress in advancing our systems to complement IFAD’s work in support of poor rural farming families and look forward to further success as we continue to work together to service poor, rural families with valuable and productive information.

Owen Barder, CEO

Hassan Ammar, PAD Project Manager, reports on the implementation of an exciting new pilot in Pakistan.

Over the course of the past four months, our team in Pakistan has commenced implementation of a groundbreaking new pilot to promote the adoption of two zinc biofortified wheat varieties to smallholder and progressive farmers in Punjab Province.1 The project is being implemented in partnership with HarvestPlus, a program of CGIAR, whose mission is to “build sustainable food systems and bridge the gap between agriculture and nutrition… by breeding vitamins and minerals into everyday food crops”.

Zinc deficiencies are particularly prevalent in low- and middle-income countries, who bear a disproportionate burden of micronutrient deficiencies more generally. Adequate zinc micronutrient consumption is critical for gene expression, cell division, the development of immunity, and reproduction. A zinc deficient diet can weaken and undermine the development of immune systems, trigger stunting and inhibit cognitive functioning in children, and contribute to pregnancy complications. Among young children, a zinc deficiency significantly increases the risk of severe outcomes associated with diarrhea, pneumonia and malaria, including death.

Rigorous prevalence studies are limited, however available information suggests widespread zinc deficiency among children in Pakistan: More than one third of preschool-aged children and more than half of primary school children were assessed to be zinc deficient. While data is lacking, studies also suggest an alarming rate of zinc deficiency among pregnant women, which may contribute to Pakistan’s poor infant and maternal mortality rates.

Sixty percent of the average Pakistani citizen’s daily diet consists of wheat products. For poor, rural and wheat farming populations, this is likely to be higher. Encouraging the adoption of zinc biofortified wheat may significantly boost zinc consumption within smallholder households, with positive implications for the health of smallholder families. HarvestPlus estimated that regular consumption of zinc biofortified wheat can provide up to 60 percent of daily zinc needs for women and children, which is 30 percent more than commonly grown varieties. Additionally, zinc biofortified varieties offer additional advantages to farmers – they have been developed to be more disease resistant, and are associated with higher yields than traditional varieties.

The pilot, which commenced in October, is focused on raising awareness about the nutritional and agronomic benefits of zinc biofortified wheat. Launched during the 2020 Rabi wheat season (the second sowing season which runs from October through December, and which is harvested in April through May), the pilot will continue until March 2021.

PAD has partnered with HarvestPlus to send customized SMS and Push Calls to 100,000 farmers in five districts of Punjab in Pakistan. Advisory content provides information in local languages (Urdu and Saraiki) to farmers. In addition to pushing advisory information to farmers, the pilot includes a helpline, backed by a call center, which farmers can call with questions, and which is used to obtain farmer feedback about adoption of biofortified crops and to conduct farmer profiling via surveys and focus groups.

To date, approximately 1million SMS and 967,668 robocalls have been placed to farmers. Push call content has focussed on the benefits of zinc for nourishment, immunity against diseases, and the relative resistance of Akbar19 and Zincol16 wheat varieties to rust and other wheat pests and diseases relative to wheat varieties more commonly planted in Punjab.

A total of 1,325,464 SMS have been sent to farmers in a series of 17 campaigns. Messages provide information on the signs of and risks posed by zinc deficiency, the agronomic and nutritional benefits of zinc wheat, and the commercial benefits of zinc wheat to farmers.

This project and the messages to be sent to farmers are approved by the Government of Punjab, Department of Agriculture Southern Punjab, which plays a critical role in ensuring the smooth functioning of the agricultural system in Pakistan. Working hand in hand with government officials, PAD and HarvestPlus will bridge the gap between the public and private sector by linking farmers to seed providers.

This project will also facilitate the use of seed diffusion where farmers pass on seeds to their friends and family but also private sector seed sales when farmers and larger growers are looking for the latest and best varieties.

By working with the relevant Departments of Agriculture and conducting surveys, PAD will be able to ascertain how successful HarvestPlus and PAD have been in their partnership to expand the reach of nutritious zinc-biofortified wheat in Pakistan by leveraging mobile communications to engage progressive and smallholder farmers.

In the Pakistan project, HarvestPlus and PAD aim to track the specific reach and delivery of the mobile messages against subsequent farmer-reported seed transactions to demonstrate the project’s impact and return on investment. We look forward to reporting our learning from this pilot in future blog posts.

1As determined in the most recent Agriculture Census, a farmer working 25 acres or more is designated as a “progressive farmer”. In 2010, farms with less than 5 acres of land constituted 64 per cent (5.35 million) of the total private farms but they operated only 19 per cent (10.18 million acres) of the total farm area. Whereas, the farms that were of 25 acres and above in size, comprised only 4 per cent (0.30 million) of the total farms but they commanded 35 per cent (18.12 million acres) of the total farm area. The average size of farm in the country was 6.4 acres whereas the cultivated area per farm was 5.2 acres.

**UPDATE** On December 15, 2021, the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture canceled the project that had been awarded to PxD by public tender. We continue to work with our regional partners, IICA, and the Government of Brazil to identify complementarities and further opportunities for collaboration.

As those of us in the northern hemisphere return to our home offices after an unusual summer, at PAD we do so cognizant of farmers we serve who continue to navigate a period of escalated uncertainty and precariousness due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At PAD we are motivated and optimistic about the ways in which we can do more to understand our farmers’ evolving needs, and about how we can equip them with empowering information to more effectively mitigate new risks, insulate their households from the pernicious impacts of the pandemic, and promote more efficient and productive agricultural practices.

We excited to commence implementing operations supported by a grant and partnership with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (signed on the 28th of August – see our most recent quarterly report for more information) to support the digital extension activities in Kenya, Pakistan and – a new country for PAD – Nigeria.

We are also excited to be pursuing a new partnership with the Government of Brazil and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture. This new opportunity will scale our digital extension work to farmers in a new hemisphere, on a new continent, and in a new geography, at a time when farmers’ informational needs continue to escalate, and in-person sources of information have become more tenuous.

Watch this space!

Make an Impact Today