2022 was a tremendous leap forward for research at PxD. Our research and operations teams completed a total of eight A/B test experiments and impact evaluations. We collected data in person and over the phone from approximately 20,000 survey respondents in 27 distinct surveys that took place in Kenya, Ethiopia, Colombia, Pakistan, and three states in India.

We generated new insights to build future programming such as an SMS agro-dealer directory to reduce input market information frictions, built evidence-based proofs of concepts for innovative service design such as WhatsApp-based crowdsourcing chatbot and learned to leverage research partnerships for scalability with dairy cooperatives. We used research insights to shift and refine our approach and we are excited about further impact evidence from forthcoming analysis in 2023.

Devastating events in 2022 from drought in the Horn of Africa to the 100-year flood in Pakistan emphasize that climate change is one of the most urgent challenges facing our users. As such, we have intensified our research efforts to identify interventions that can improve smallholder livelihoods whilst incorporating climate adaptation and mitigation efforts into our existing services. We’ll continue this innovation research agenda in the coming year to explore high-value innovations to supplement our core digital agricultural advisory.

New insights to build future programming

Across a diverse portfolio of research projects, we have demonstrated the value of PxD’s services and contributed to an expanded knowledge base on digital agricultural extension. A particularly promising finding is establishing that digital tools can be effective in improving in-person extension services.

Performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages could increase extension volunteers’ performance: Through a large-scale randomized evaluation in Rwanda, we demonstrated that performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages – particularly goals that were ambitious but attainable – could improve community extension volunteers’ (known as Farmer Promoters – FPs) performance and therefore generate positive impacts on farmers’ outcomes. Sending goal reminders to FPs significantly increased the number of farmers trained by 3.1 percent, led to a significant 4.3 percent more training sessions being delivered, and increased farmers’ registration for subsidized inputs by 1.9 percent (statistically insignificant) over FPs who did not receive goal reminders. Given that the unit cost for each SMS is $0.006 and the average number of farmers assigned to each of the ~14,000 FPs across Rwanda is 190, the effect sizes of these messages are likely to be highly cost-effective.

The results of the Rwanda project support the expansion and replication of extension agent interventions in other settings targeting different populations in the future. In addition, these results point to areas for future research and development that could enhance the effectiveness of extension agent services. For example, we are interested in exploring how digital tools can be used to help extension agents set performance-increasing goals, direct them to farmers most in need, and extend information access to farmer populations that may not benefit from direct digital advisory services.

A digital directory of agro-dealers has the potential to increase the adoption of recommended inputs: In Kenya, we found evidence that farmers can benefit from the provision of an SMS agro-dealer directory by reducing input market information frictions. Our preliminary empirical findings suggest that – particularly for a directory that includes stock and price information about agro-dealers – access to this tool prompts farmers to refine their choice of agro-dealers before an in-person visit. Farmers in the treatment arm who had access to the agro-dealer directory and stock information contacted 21 percent more agro-dealers, but visited 4 percent fewer agro-dealers relative to the control group which did not have access to the tool. This suggests that farmers in this treatment arm used the contact information to call more agro-dealers before spending time and money to travel to the shops themselves.

Farmers given access to the agro-dealer directory were more likely to purchase PxD-recommended inputs and experienced fewer stockouts than those who didn’t have access to the directory. When pooling the two treatment arms, we observe that consistent with PxD’s advisory recommendations, treated farmers were 6 percent more likely than control farmers to use hermetic bags to store maize – a practice shown in rigorous studies like Ndegwa et al. (2016) to prevent post-harvest losses from pests. Farmers in the treatment arm with access to the directory but not stock info appeared to contact and visit agro-dealers at the same rate as the control group but then were 22 percent less likely than the control group to report facing an input shortage when they shopped (meaning they were more likely to find and purchase the product they were looking for).

Building on these promising findings, we hope to identify opportunities to further develop a scalable digital agro-dealer directory tool. Specifically, we are interested in exploring ways to onboard a large number of agro-dealers and update the stock information at a low cost.

Building proofs of concepts

Digital peer groups increase farmer interactions and potentially increase the adoption of recommended practices, but we need creative ways to form groups at a low cost: Various research projects aimed to demonstrate proof of concept for novel interventions that PxD was exploring for the first time. For example, we now have empirical evidence that an intervention in Kenya to organize farmers into groups and send them SMS nudges to communicate with each other was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members. Treatment farmers who were organized into digital peer groups had higher interaction levels than their control group counterparts and were 43 percent more likely to meet with their group members on a farm than control farmers. Interacting with one’s group members on a farm was also associated with increased adoption and knowledge of recommended practices.

A gig-worker model for crowdsourcing agricultural field photos has the potential to generate real-time data on field conditions: We acquired institutional knowledge, both technical and regulatory, to build and operationalize crowdsourcing platforms to demonstrate the feasibility of crowdsourcing information from agro-dealers and farmers in Gujarat. In a pilot, we set up a WhatsApp chatbot, integrating a WhatsApp Business Account with our in-house user communications platform, Paddy, to guide users through a systematic inspection of a field for crop health issues and send reports back to PxD with their findings.

Eighteen of our recruited farmer agents consistently engaged with the program over 10 weeks, with a median of nine crop health reports per agent. The quality of field reports was high – approximately 94 percent of reports are usable. In total, we received 220 field reports with accurate GPS locations and usable photographs. Each of these reports costs INR 125 (USD 1.67), which is substantially below the cost of a 15-minute phone survey. This suggests that crowdsourced data could be a cost-effective method of collecting local data.

PxD aims to further build this knowledge to crowdsource various types of information and use it to improve future service offerings by customizing advisory to be more locally relevant and actionable.

Working with smallholder farmers in the fight against climate change

We are intensifying our efforts to provide information to smallholder farmers that will allow them to make informed decisions to reduce the risks that climate change presents to their livelihoods and to consider adopting practices that can actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We approach this work with the guiding principle of farmer welfare first: smallholder farmers cannot be expected to pay the price for climate change mitigation. Climate change-related advisory should directly support livelihood gains via improved agricultural output or renumeration .

PxD, in collaboration with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD), worked to assess opportunities to benefit poor farming communities through their participation in climate mitigation activities and to direct tangible returns to participating smallholder communities.

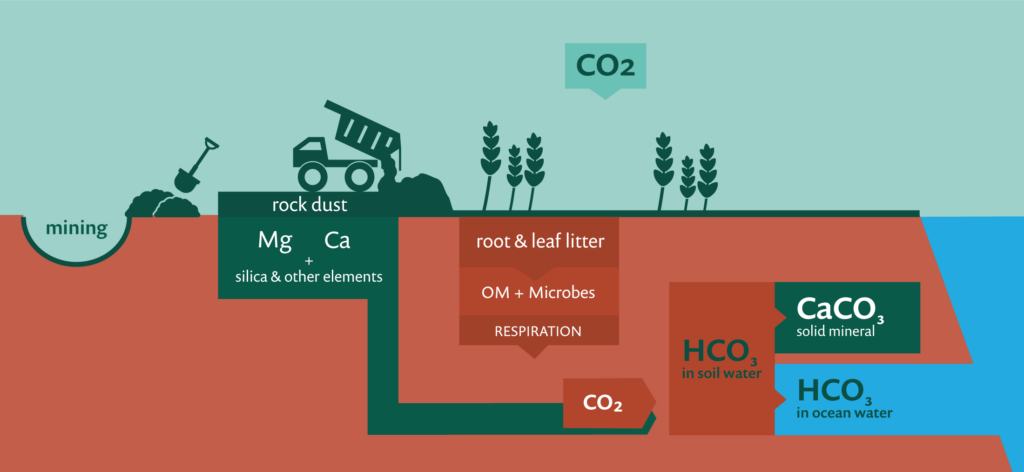

The PxD-IGSD collaboration has focused on exploring four mitigation areas with most promise in agriculture: Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced rock weathering; Carbon dioxide sequestration with organic carbon storage in soils and plant biomass; Nitrous oxide mitigation through precision nutrient management; and Methane mitigation in dairy through improved livestock feeding practices.

- Enhanced rock weathering (ERW), an emerging technology that permanently draws down carbon from the atmosphere and has the potential for agricultural co-benefits makes it an attractive mitigation strategy in the smallholder farmer context.

- There is evidence that conservation agriculture practices that many farmers are already familiar with – such as reduced tillage, the use of cover crops, and intercropping – promote the sequestration of organic carbon in soils.

- In terms of nitrous oxide emissions, simple decision support tools following the Site Specific Nutrient Management approach, i.e. Leaf Color Charts (LCC), have been shown to reduce nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use as well as improve farmer outcomes.

- For methane, improving feeding practices that increase milk production and closing the dairy yield gap in the Global South per cow can lower the methane intensity of production and contribute to methane mitigation, as well as improving farmer livelihoods.

We’re excited to be on the cutting edge of exploring the potential of these climate change mitigation opportunities- like scoping a digital version of Leaf Color Charts to enable the tool to reach a wider scale and Advanced Market Commitments to incentivize R&D for enhanced rock weathering. Our research initiative with IGSD has enabled PxD to identify future activities within each opportunity area to advance climate change mitigation in the smallholder farmer context and we are actively pursuing partnership and funding opportunities to advance these activities.

Learning to leverage research partnerships for scalability

Partnerships have proven to be a critical pathway to increasing impact and scaling evidence-based programs across our project portfolio.

By collaboratively identifying and developing high-impact opportunities with dairy cooperatives in Kenya, PxD has identified a new partnership model in which PxD serves as a technical and analytical partner for innovating and testing service offerings for cooperatives, and builds cooperatives’ capabilities for generating greater impact at scale. We kicked off the partnerships with Lessos Dairy and Sirikwa Dairy by adapting an asset-collateralized loan product for water tanks which has been shown to dramatically increase access to water tanks among dairy farmers in a research study (Jack et al, 2022) and setting up an evaluation to measure its impact on economic and household outcomes.

In Gujarat, India we surmise that identifying low-cost and scalable approaches to crowdsource pest information will require leveraging local organizations and existing social networks for cost-efficient recruitment and training of agents.

To further explore opportunities to support women farmers in Gujarat, we successfully established partnerships that allow us to better understand the constraints women farmers face in engaging in economic activities and their access to information and other services. These partnerships allow us to design and implement group-based digital services to address those specific constraints.

Insights to shift and refine our approach

Our scoping activities allowed us to identify when a change in approach was needed or when interventions did not turn out to be as promising as we had hoped.

In the dairy sector in Kenya, we learned that existing market and coordination failures, such as credit constraints, need to be addressed to create an environment in which digital advisory can effectively improve smallholder dairy productivity.

In testing social learning mechanisms in Kenya, we did not find evidence that the designed intervention increased farmers’ knowledge or the likelihood of adopting recommended practices, despite finding that peer learning was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members.

While subsequent qualitative interviews suggest that some farmers visited the farm fields of their peers and experimented with the recommended practices in a small portion of their plot, developing the digital peer group advisory further is likely to require a substantial investment in basic research to understand farmers’ social learning process and identify creative ways to reduce the relatively high costs associated with forming peer groups.

Finally, we learned to exercise caution in working with established women’s groups in Gujarat in a way that does not exacerbate local power dynamics within communities to ensure PxD’s services are designed in a sensitive way to promote the inclusion of marginalized groups that may face particularly challenging digital access gaps.

Looking forward to continue building our evidence base

In the coming year we are looking forward to continuing to build our evidence base with forthcoming insights on PxD’s impact on farmer welfare from several large-scale RCTs in India, Uganda, and Kenya.

For the impact evaluation of our largest service offered to date for rice farmers in India, endline data collection and analysis are expected following the second season of implementation in 2023. In addition to outcome data on farmers yields and profits, we’re excited to generate additional insights on scalable measurement options for detecting yield changes among rice farmers using remote sensing data.

In Uganda, our work with coffee farmers enabled PxD to explore several dimensions of digital advisory, including comparing a stand-alone digital advisory service to the provision of digital advisory as a complement to in-person training and studying social spillovers from our advisory services. An endline analysis of the effects of this program will be forthcoming in 2023.

We are also excited to generate initial insights on the impact of asset-collateralized loans for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. Using frequent administrative data from dairy cooperatives on milk production, we’ll be able to understand how improved access to water tanks helps farmers mitigate productivity shocks and domestic water shortages as farmers adapt to more dry spells from a changing climate.

In addition to evaluation research with rigorous RCTs, we look forward to building out our research innovation agenda in the coming year. We are exploring a variety of new, evidence-based high-value product innovations that can build on our agricultural impact for smallholder farmers, such as interventions to facilitate market linkages and access complementary financial services. We are committed to using rigorous evidence and deep user research to identify and prioritize which ideas to pursue.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2023! If you’d like to learn more or partner with PxD on specific areas highlighted please get in touch!

Accurate, medium-range weather forecasting information can help mitigate smallholder farmers’ exposure to climate-related risks. PxD is in the process of launching new products to assist smallholder farmers to make more informed and timely decisions based on weather information. In this post, we outline the contours of our exploratory research to integrate weather forecasts into Coffee Krishi Taranga (CKT), our existing digital advisory service for small coffee farmers in India.

Coffee is a notoriously fickle crop. For example, heavy rainfall can damage crops, result in premature fruit-drop, increase the incidence of pests, and wash away fertilizer with negative implications for plant nutrient levels. Increasing weather variability and the incidence of extreme weather events associated with climate change will have significant negative effects on coffee producers. Given the sensitivity of the crop — and yields — to fluctuations in the weather, coffee farmers are likely to derive meaningful benefits from accurate and timely weather forecasts. Insights from our CKT learning agenda will be used to inform the design of a larger evaluation of the weather-integrated service and to scale an enhanced service to over 150,000 coffee farmers across four Indian states (Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh – an expansion state).

The motivation

PxD delivers CKT in partnership with the Coffee Board of India and with support from the Walmart Foundation. Since 2018, CKT has delivered a two-way interactive voice response (IVR) service with two principal components: an outgoing push call service that provides regular advisory to coffee growers via their mobile phones, and an inbound hotline that farmers can call to access free information services. In April 2022, CKT reached just over 70,000 smallholder coffee farmers in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

More accurate information about medium-term rainfall — with a lead time of up to 15 days — will enable farmers to make informed decisions about applying nitrogen fertilizer and increase the likelihood that they apply this input during dry spells to reduce run-off and leaching. Similarly, if farmers are alerted to impending heavy rain, they can leverage this information to alter harvesting times or take other precautionary measures to protect crops and insulate yields.

Speaking to farmers to inform design and process

In interviews conducted with coffee growers in August 20211 Described further in an earlier blog post that outlined findings from the landscape analysis of coffee production in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh relating to sustainability, market linkages, and gender., only 16% of respondents reported accessing forecasts (N=73). Integrating weather information into CKT’s existing services will broadcast weather forecasts to farmers tailored to their specific contexts and complement these forecasts with agronomist-designed advice. Exploratory and pilot research will be implemented between May and December 2022 in three important coffee-growing districts in Karnataka: Chikmagalur, Hassan, and Kodagu.

Studies conducted in other contexts find that farmers form subjective expectations about upcoming weather events based on various factors, including their past experiences, local rules of thumb, existing forecast information, the costs and benefits of acquiring such information, and perceptions about how relevant weather-related risk is to their incomes2As demonstrated in Giné, X., Townsend, R.M., & Vickery, J. (2015). “Forecasting When it Matters: Evidence from Semi-Arid India.” Working Paper.. These expectations inform behavior over the course of the coffee crop cycle as farmers make decisions relating to input and investment choices, the timing of activities, and so on. The sum of these decisions, in turn, influences outcomes that farmers (as well as researchers and practitioners) are interested in – notably plant health, yields, costs, and profits. The goal of this research is to understand each of these elements through measurement and service pilots, A/B tests, qualitative interviews, and in-person workshops with farmers, agronomists, and extension agents.

Coffee laborers having lunch on a coffee farm.

Iterating relevant service design and a weather service at scale

Commencing in May 2022, we will conduct multiple rounds of in-depth qualitative interviews with men and women coffee farmers. The sample will include farmers working a range of landholding sizes and will include both smartphone and feature-phone owners. The objective of the first set of interviews is to better understand how coffee farmers make decisions relating to the timing of agronomist-identified, weather-dependent coffee activities: fertilizer and lime application, coffee pruning, shade regulation, and harvesting. We hope to identify how weather fits into these decisions and what other factors influence the timing of these activities. If other limiting factors (such as the availability of an input) impact timing to a greater extent than the weather, forecast information with short lead times may not help farmers optimally time their practices without access to complementary inputs or information. These interviews will also help us identify how farmers interpret weather forecasts they already have access to, what impact incorrect forecasts have on their activities and on their trust in forecasts and the extent to which farmers discuss their expectations of upcoming weather with other members of their communities.

As detailed in previous blog posts about our weather-related work, PxD is partnering with leading private forecast provider CFAN (Climate Forecast Applications Network) to develop calibrated custom forecasts. Using weather forecasts from CFAN provides access to a continuous stream of information, which includes the numerical quantity of a rainfall event being forecast, numerical probabilities associated with a forecasted weather event, and error margins on the quantity of rainfall forecast for each of the upcoming 15 days3Read more about our collaboration in this previous blog post. Building on the first set of qualitative interviews, we plan to assess (1) whether farmers comprehend and have an appetite for probabilistic and uncertain information; (2) whether specific forecast attributes or lead times meaningfully change farmers’ expectations of upcoming weather; and (3) which combinations of attributes and lead times aid decision-making for each weather-dependent activity. We plan to gauge farmers’ understanding of probabilities and uncertainty in a second set of in-person interviews to whittle down the forecast formats that will be most useful in this context.

PxD facilitated Interviews with coffee growers.

Coffee farmers in a subset of villages in our three study districts will then be invited to participate in in-person workshops, where they will interact with different forecasting formats. The workshop will be in the form of a ‘lab-in-the-field experiment’, where participants engage with an interactive platform that presents weather forecasts together with incentivized agricultural decision-making scenarios. Utilizing participants’ decisions on the platform, an ‘in-scenario’ weather ‘realization’ will be simulated, allowing participants to accrue a higher payoff for a ‘better’ decision. The best-performing forecast will accrue the highest cumulative payoff across participants and will inform our understanding of which forecast formats most effectively aid decision-making. The ‘best-performing’ customized-to-context weather forecast will then be piloted in the field among a sample of existing CKT users to evaluate whether it improves decision-making in a real-world setting.

Delivering an effective weather-based advisory service via mobile phone also requires that we ensure that users engage with and use the information being delivered. To this end, we plan to run A/B tests to optimize the frequency with which weather forecasts are delivered, the length of messages, and other service features.

We are optimistic about the utility of weather forecasting information and its potential impact on smallholder farmers — and their productivity — as they make what we hope will be more informed decisions. We are excited to deploy this information and make it actionable for smallholder coffee producers on our CKT service. Watch this space!

Precision Development (PxD) recognizes that the informational needs of poor women farmers, and the challenges they confront, are unique. As a consequence, our services must be tailored to reach and be relevant to the needs of women users. Driven largely by the onboarding of women active in livestock-related activities, the number of women farmers active on platforms built by PxD increased by approximately 46% over the course of 2021. This included the onboarding of over 150,000 women farmers to our Ama Krushi (AK) service, which we deliver in partnership with the Government of Odisha, India. As we mark International Women’s Day, we reflect on efforts we have made to improve our understanding of gendered divisions of labor and bargaining power within Odishan smallholder households, and steps we are taking to assist women farmers make more informed decisions.

Scoping work undertaken by PxD suggests that women farmers spend more productive hours on livestock farming than men. However, women farmers disproportionately lack access to mobile phones and, by extension, digitally conveyed information. Perhaps the largest impediment to increased engagement with PxD’s advisory on the part of women farmers is access to information, and patterns of information sharing within households. This could have knock-on effects that undermine women’s productivity and bargaining power within the household. To further understand these dynamics, we explored if sending messages encouraging information sharing within households can assist in breaking this cycle.

The motivation

Gendered roles in livestock farming

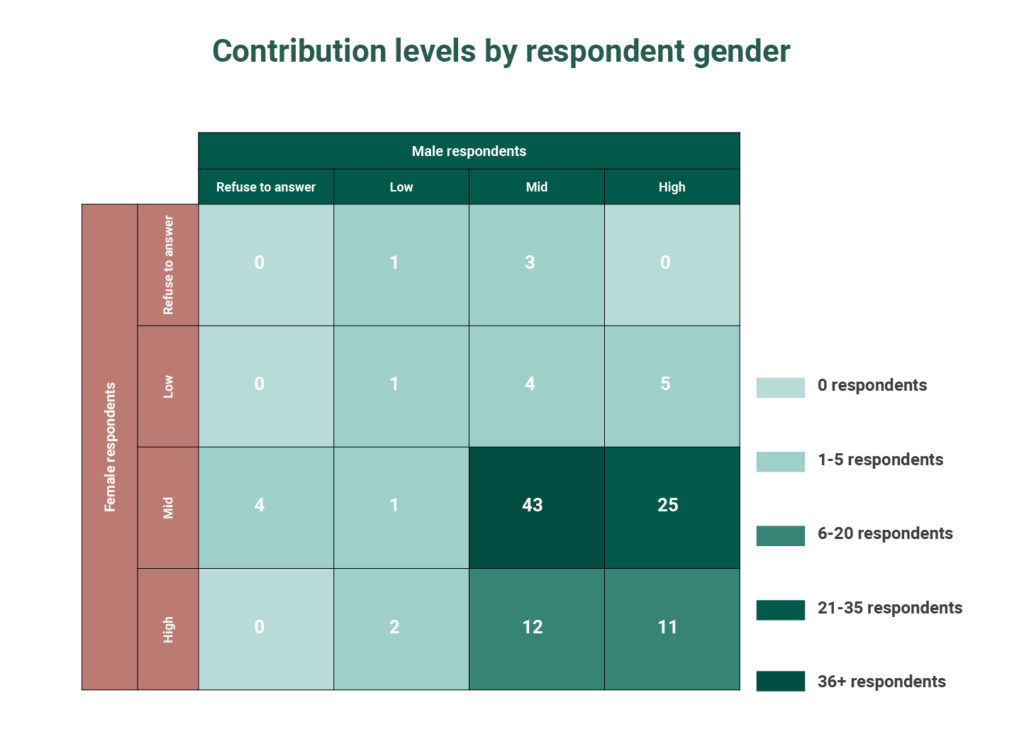

In June 2021, we conducted a survey to improve our understanding of gender roles in livestock farming in Odisha. The sample consisted of 5,354 AK farmers who have subscribed to livestock-related advisory, practice cow-rearing, and had received at least one livestock advisory message via the AK service. The sample included equal numbers of male and female users and was stratified by the farmer’s district. Of this sample, we successfully surveyed 1,475 AK farmer users.

We found that, on average, women AK users allocate more time to livestock rearing and household chores than male AK users (Table 1). Relative to male AK users, women spend less time on cropping activities and on other non-livestock-related income-generating activities.

The survey also found that men AK users are significantly more likely to perform—and be the primary decision-maker for—livestock-related tasks that require travel outside of the home. These types of activities include veterinary visits, purchases of livestock-related inputs, selling milk, and sourcing fodder. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to be involved in livestock-related activities performed at home, such as cleaning sheds, feeding, and milking animals. Given the heavy involvement of women farmers in livestock-related activities, it is important that livestock advisory broadcast via our AK service is communicated to women household members if it is to be practical.

Importantly, many income-related improvements in livestock outcomes—such as increasing milk yields and successful breeding—depend on the coordination of multiple tasks performed by both men and women within a household. For example, successful breeding requires the completion and timely sequencing of tasks and processes, including the provision of sufficient nutrition, deworming, heat detection, and accessing artificial insemination (AI) services. To achieve these ends, it is important that livestock advisory reaches both women and men in the household, and that intra-household communication is sufficient to coordinate improved livestock outcomes and household welfare maximization.

Barriers to information for female farmers

Reaching female farmers through mobile phone extension services is challenging as men farmers are more likely to be the primary owners of mobile phones in the household (OECD, 2018; Baroni et. al., 2018). Evidence suggests that women registered as subscribers to PxD’s mobile advisory services have shared access to phones and male partners are the devices’ primary users. PxD uses polling surveys to maintain and improve quality service delivery, and to source feedback from users. Women AK users polled for our May 2021 livestock survey self-reported lower pick-up rates than male respondents. However, actual outbound AK administrative data does not reflect a gendered disjuncture in pick-up rates. An explanation of this could be that the household member who picked up the phone when an AK call was placed to a women farmer was not the registered woman user. Similarly, during this gender survey in Odisha, we asked the respondent who picked up the phone if they were the registered AK user. In the case of registered women AK users, someone else picked up the call 12% of the time, compared to only 5% in the case of registered men AK users. This difference is statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that when a phone is being shared, registered users that are women have less time with the phone than men. Given the greater engagement of women in livestock-related activities, this gendered barrier in mobile phone extension services is a significant challenge.

To gather more evidence on AK users’ individual access to mobile phones, we asked about a quarter of the AK users in the Gender Scoping Survey (n=370) about their typical access to mobile phones between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m. every day. Women AK users reported less availability at all times of the day (Figure 1). However, the difference is only statistically significant at the 10% level for the 3 p.m. to 4 p.m. period (both in the full sample and the married-only sample). Due to the smaller sample size, we may be underpowered to detect other differences.

Figure 1: Gender differences in individual access to phone

Interestingly, when we restrict the analysis to household heads only, women report higher average access to their mobile phones than men. The Gender Scoping Survey finds that the time-use patterns of women heads of households closely follow those of men heads of households (Table A1), there are a few possible reasons for this deviation in self-reported access to mobile phones. A possibility is that male heads of households are more likely to share their phones with their spouses or children. By contrast, the Gender Scoping Survey found that women heads of household are typically unmarried (or widowed, separated, or divorced) and therefore may not need to share their phones as much as men heads of household.

Consistent with the evidence above, the Gender Scoping Survey finds that men AK users are significantly more likely to cite Ama Krushi as a primary source of livestock information than women AK users (Table 2), while the polling survey finds that women AK users are significantly less likely to answer knowledge questions based on livestock advisory sent in the month preceding the survey correctly.

Importantly, AK users seldom cite their spouses as a source of livestock information or as someone they discuss new livestock information with, a gap in intra-household information transfer that PxD could potentially influence. Improving intra-household communication can potentially increase the reach of PxD’s advisory to existing registered women AK users who may not be picking up the outbound advisory, but also extend the reach of our advisory to the wives and women children of men registered as AK users on the livestock service.

Adoption: Individual vs joint access to information

To better understand intra-household dynamics of information transmission and adoption, we asked respondents to the Gender Scoping Survey if they find it easy to convince their spouses to adopt new livestock practices when they receive such information. Of the respondents, 76% replied yes to this question, and we found no significant differences by gender. This percentage increased to 90% when we asked if listening to the advisory jointly with their spouses on the phone’s speaker would make it easier for them to adopt the recommended practices. A gendered analysis of this increase did not detect a statistically significant difference between men and women users.

Therefore, we find suggestive evidence that getting livestock recommendations to female farmers is the primary barrier to increasing the benefits accruing to our digital advisory. When women farmers receive advisory, they may be just as likely to influence adoption decisions as men farmers. Additionally, increasing the shared knowledge of the spouses has a greater potential to increase adoption rates than individual access to information.

Calibrating solutions

The phone’s speaker

One possible solution to reach more women farmers and promote information sharing among spouses is to encourage respondents who pick up advisory calls to use their phones’ speakers to listen to the advisory with other household members. We wanted to pilot a nudge to male livestock farmers to listen to advisory messages with their speakerphone turned on with other household members engaged in livestock-related activities. However, we first needed to know if farmers could use their phone’s speaker. We conducted a speakerphone feasibility survey to understand:

- Whether farmers can use their phone’s speaker by themselves.?

- If not, can we deliver simple instructions during the phone call so that farmers can use the phone’s speaker?

- Whether we need to build in a time allowance for farmers to activate their speaker and listen to advisory with their household members.? If so, then how much time?

- Whether farmers are willing to use their phone’s speaker and listen to the advisory with other household members.?

Of the 90 respondents who consented to the survey, 76.67% could turn on their phone’s speaker without any instructions (67.92% of feature phone users and 89.19% of smartphone users). Following simple instructions on how to use their speaker, 84.44% of respondents could do so. Overall, 89.19% of respondents were able to turn on their phone’s speaker within 10 seconds of being asked to do so, and of those, 96.2% were willing to use their phone’s speaker to listen to future AK advisory with their family members. As a consequence we are confident there are no large technical or aspirational barriers to adopting the nudge and we moved to pilot it in different forms.

Assessing potential interventions

These results encouraged us to test nudges in three ways for one month:

- A separate IVR nudge asking users to call into our inbound service for joint-listening over their speakerphone (n=600);

- A text 20 minutes before the weekly livestock advisory asking them to turn on their phone’s speaker and listen to the advisory with members of the household involved in livestock-related activities (n=500);

- An additional script at the start of the weekly livestock outbound with the same nudge as in Method 2 (n=500).

All the nudges were sent between 6 and 8 pm based on the findings on joint availability in the gender survey. Before implementing an A/B test to measure the effectiveness of these interventions, we conducted small pilots to select the most promising methods.

In the pilot, we did not find that nudging farmers to use the inbound services (Method 1) was very successful. We sent a nudge call to 600 farmers, asking them to dial a toll-free number to listen to the livestock advisory on the speakerphone with their family. A total of 12 people (and 14 total calls) dialed into the service within a week of the nudge, but none accessed the feature to listen to the livestock advisory. While this does not eliminate the possibility that nudged farmers discussed the call’s content with their spouses, we did not pursue this method to achieve the specific objective of joint listening.

For farmers who were nudged through an SMS (Method 2), using a short survey, we found that only 4% of respondents recalled the nudge’s content (n=126). We concluded that this method was unlikely to translate into increased joint-listening or improved knowledge and adoption.

Using another short survey, we found that farmers who were nudged in the introduction of the weekly livestock outbound advisory (Method 3) were 22 percentage points more likely to report having listened to the advisory message jointly with household members than those who received the regular outbound advisory (ntreatment = 61; ncontrol=45). As this method showed the most promise, we conducted an A/B test deploying it to 17,000 farmers over ten weeks starting in late October. We are currently reviewing data from this test and will share the learnings when they are available.

The authors would like to thank Qi Xue, PxD Intern, who offered valuable assistance in executing the surveys and preliminary analysis underpinning this post, as well as Niriksha Shetty, Tomoko Harigaya, and Otini Mpinganjira for their insights and guidance.

Appendix:

Precision Development’s goal is to generate large aggregate impacts for the poor. Research plays a central role in advancing that objective. In a collaborative post, our Research Team surveys their work in 2021 and outlines an exciting portfolio of activities planned for 2022.

As a recent video produced by our colleagues at J-PAL recounts, Precision Development would not exist were it not for the practical application of research in the world. By intentionally deploying experiments and other methods, we continue to use research to inform the design of our services (innovation research) and to evaluate our impact (evaluation research), and these two types of research often overlap. PxD’s research practice aims to integrate with service design and delivery, and we leverage research to iterate our theory of change, identify learning objectives, and gather insights in every program and initiative.

Needless to say, in 2021 we were busy! Our research and operations teams have collaborated on 26 experiments, of which 14 are completed and 12 are ongoing.

Evaluation Research

At the end of 2021, PxD has three ongoing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to rigorously evaluate the impact of our services on downstream user outcomes, such as the adoption of improved farming practices, improved agricultural yields, or impacts on learning. In addition to these three evaluations of our own services, we are collaborating with One Acre Fund (OAF) to evaluate aspects of their work with Farmer Promoters.

Excitingly, PxD is running a large-scale RCT with nearly 15,000 rice farmers in India to estimate the impact of the Ama Krushi service on farmers’ practices and yields, and how the magnitude of these impacts vary by farmer characteristics. Data on production costs and revenues will be collected from a subset of farmers for a back-of-the-envelope calculation on the service’s benefit-cost ratio. This RCT also aims to test the effectiveness of using satellite-based imagery to detect yield changes in GPS-measured smallholder rice plots and to compare these to self-reported farmer yields. Early in 2022, we will conduct the midline survey and process satellite images to assess the impact in the first season. We are eager to share our initial findings!

In western Uganda, PxD is collaborating with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the Hanns R, Neumann Stiftung (HRNS), and Technoserve to measure the stand-alone impact of PxD’s two-way voice-based advisory service and the complementary impact of digital reminders implemented by PxD as part of the Uganda Coffee Agronomy Training (UCAT) program. This RCT plans to integrate the use of machine learning to identify agricultural practices that have the highest impact on improving coffee yields and to identify farmer characteristics that are most closely associated with the increased adoption of such practices. The COVID-19 pandemic pushed back the initial implementation schedule for UCAT and we now plan to collect endline data for approximately 4,000 farmers in 2022.

In the education sector, Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and PxD have concluded data collection for a randomized evaluation to assess the impact of our two-way SMS math education service, ElimuLeo, on learning and knowledge. Implementation of the RCT has now concluded and we have extended access to the platform to children in the control group. We have recently surpassed the milestone of over 500,000 problems solved on the platform!

Since 2018, PxD has partnered with One Acre Fund (OAF) to test low-cost incentives to enhance the performance of approximately 11,000 Rwandan volunteer extension agents, commonly known as Farmer Promoters (FPs). With one FP in each of Rwanda’s 14,500 villages, PxD’s collaborative intervention targets a majority of FPs in the country. Importantly, FPs do not receive monetary compensation for their service, but rather receive in-kind benefits such as free inputs. Throughout 2021, PxD and OAF have been conducting an RCT to examine whether motivational SMS messages improve FPs’ performance, and to test whether motivational messages designed to appeal to the FP’s specific personality traits lead to improved FP performance and farmer outcomes. This evaluation includes three main interventions: a subsidized input promotion campaign, a demonstration plot and farmer training campaign, and an agroforestry tree planting campaign. We aim to launch endline surveys in early 2022.

Service Design and Innovation Research

As part of our efforts to leverage research to improve service design and delivery, we often conduct rapid hypothesis testing. We are also exploring ways of increasing engagement with our Ama Krushi push call service. In 2021 we deployed an A/B test that experimented with sending “heads up” SMS messages at different times to alert farmer users of an impending IVR call from the Ama Krushi service. Results are very promising: sending an SMS reminder 10 minutes before a service call increases pick-up rates by 5.9 pp (a 17% increase from the control mean pick-up rate of 34%). Conditional on picking up, the 10-minute SMS reminder also increases average listening rates by 4 pp (a 25% increase over a control mean of 15.4%). Considering both the success of the 10-minute reminders and the relatively high costs of sending SMS messages via the Ama Krushi service, one implication of this experiment would be to send short SMS reminders to farmers who are at risk of becoming inactive on the service to nudge engagement for a limited period and to promote recommendations that have particularly high-impact or are time-sensitive.

Reminders also play an important role in nudging farmers to take action on optimal planting dates. Planting at the optimal time is positively correlated with yields, yet misconceptions, lack of knowledge, or limited resources often result in farmers planting at a later date. In the 2021 Long Rains season in Kenya, we tested whether sending SMS messages recommending optimal planting times would nudge adoption. This experiment targeted a sample of approximately 15,000 OAF farmers and included additional treatments such as messages addressing misconceptions on planting times and direct endorsements from Field Officers. We found that SMS recommendations for optimal planting times are effective in nudging average self-reported planting dates closer to the optimal date. This effect is larger for late planters. Late planters in treatment groups reported planting, on average, four days closer to the optimal date relative to the late planters in the control groups. These results are valuable for improving service delivery in Kenya and for nudging farmers toward more timely planting. We are keen to conduct further research on the mechanisms underlying planting time decisions.

A/B tests deployed by PxD have shown that a narrator’s voice can impact user engagement in various contexts. In 2021 we completed a first A/B test on our nascent program in Nigeria to measure the effect of the narrator’s gender on pick-up and listening rates for PxD’s push call platform. Over the course of a seven-week period in the Wet Season, a sample of over 45,000 farmers was randomly allocated into two groups, receiving weekly audio content narrated either by a female or male voice, respectively. We found that female farmers have systematically lower pick-up rates than male farmers, yet this gap is slightly mitigated when the narrator is female. In addition, we found that all farmers (both male and female) when listening to content voiced by a female narrator were 1.4 pp more likely to listen to the full push call, given a mean completion rate of 51.8% of the audio content. Going forward, our service in Nigeria will primarily use female narrators when recording audio content for push calls. Nevertheless, we will benefit from further research to generate evidence on the long-term effect of this action on user engagement.

Our nascent research agenda in our newest program in Colombia is leveraging past experimentation on human contact and direct endorsements, particularly when it comes to increasing user engagement in the early stages of service delivery when name recognition and trust levels are limited. We have recently concluded profiling surveys and are analyzing how user engagement with PxD’s Un Mensaje por El Campo platform varies before and after farmers receive the profiling survey. SMS messages are not broadly used by smallholders in the Meta region of Colombia and many farmers need to be guided on how to access and navigate their SMS inbox to realize that they have been receiving messages from our service. Surveys and direct contact with surveyors from our team provide an opportunity to mitigate low digital literacy and improve trust in our service.

Moreover, we continue to explore ways to support farmer access to recommended agricultural inputs. In Kenya, we are building a proof-of-concept digital tool to improve linkages between farmers and agro-dealers by providing local agro-dealer contact information on our MoA-INFO platform. This digital Agro-dealer Contact Directory (ACD tool) will help us gather insights on the perceived value of reducing search costs among farmers and agro-dealers, as well as potential effects on farmers’ input search behavior and input access. Using these insights, we can then determine if there are other low-touch, scalable engagements with agro-dealers that will help us to improve farmers’ welfare. Drawing on the evidence from the literature on digital phone books, we have launched a two-way agro-dealer pilot with over 33,000 MoA-INFO farmers and 142 agro-dealers. This pilot aims to elicit feedback from farmers and convey information about their input demand to agro-dealers, mitigating informational barriers that prevent agro-dealers from consistently stocking inventory. Farmers are often uncertain about which inputs are in stock and agro-dealers are uncertain about quantities of inputs demanded by farmers, with many reporting being out-of-stock during peak times of the year. Stock-outs raise uncertainty and search costs for farmers and can lower adoption rates for improved inputs, especially if farmers have to travel far to other markets. Experimentation with the ACD tool aims to reduce search costs and improve access to recommended inputs.

Crowdsourcing local information from farmers and other actors along the agricultural value chain holds many potential advantages for our services. The key is to identify scalable ways to crowdsource sufficiently granular information to improve the quality of our advisory content. In Gujarat, we are generating insights on the operational feasibility and scalability of collecting accurate and timely information on crop health issues from locally recruited gig workers and tracking the volume and quality of data submitted by these workers via a tailored WhatsApp chatbot.

Finally, sourcing and providing information on pest prevention and management continues to be one of our research priorities. We are particularly excited about an ongoing pilot in Karnataka, India, which is reinforcing good management practices for white stem borer, a major coffee pest. In a recent round of qualitative surveys, we found that a majority of respondents had experienced white stem borer infestation in the previous coffee season, and many farmers reported using antiquated corrective measures that are no longer recommended by the Indian Coffee Board, or even practices that have been banned. Research undertaken in 2021 on Fall Armyworm infestation in Kenya and Zambia, provides some indicative evidence that our advisory increases knowledge and adoption of recommended pest prevention and management practices, and that sending reminders for priority practices may result in higher knowledge and adoption. Building on this evidence, we are partnering with J-PAL to test whether repeating key advisory messages on white stem borer and using different types of reminders and nudges, lead to higher rates of adoption for recommended practices among a sample of 2,400 coffee farmers. This experiment is ongoing and we aim to share results by mid-2022.

Looking forward to exciting research opportunities in 2022

Throughout 2021, PxD expanded dairy and livestock advisory services in Kenya, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and India. In Kenya, we are partnering with three dairy cooperatives to iterate and build a two-way SMS advisory service for dairy farmers. Building on the results of a gender survey to assess the gendered division of labor within dairy-producing smallholder households, we are excited to commence an RCT of the service in early 2022, ahead of the Long Rains seasons. We aim to rigorously evaluate the impact of the service on milk production (both in terms of quality and quantity) and sales for a random sample of 5,000 dairy farmers using administrative data made available from our dairy cooperative partners.

Finally, we are excited about our nascent climate research agenda, which includes both adaptation and mitigation efforts, and aim to continue scoping opportunities within our services and geographies to strengthen smallholders’ climate resilience, generate scalable low-cost climate mitigation innovations, and, above all, to improve smallholders’ agricultural productivity and income. We are excited to launch new products integrating granular weather forecasting with actionable advisory in Punjab, Pakistan, and Karnataka, India. Our weather pilots aim to incorporate innovation research to understand how to communicate uncertainty and probabilistic events in low-literacy settings, as well as the value of forecasting versus tracking advisory. Moreover, after recently securing new climate mitigation funding, we are eager to conceptualize research pilots to measure low-cost scalable innovations and rigorously measure changes in both farmer and climate outcomes. We intend to establish a proof of concept for our environmental theory of change and seek further validation of the applicability of PxD’s communication for behavior change model on new research areas, such as the potential for cash payments to farmers for activities that sequester soil carbon and contribute to climate change mitigation efforts.

At PxD our decision-making draws on existing evidence and scientific knowledge; understanding about how humans, institutions, firms, and markets behave and function; contextual information and knowledge about targeted users and local conditions; and our prior experience (as well as resource envelopes and other pesky exogenous factors). Research and inquiry are critical to generating insights and uncovering new information across all of these categories of knowledge. We are privileged to work with colleagues who rigorously generate and leverage evidence to guide our work and decision-making as we develop, iterate, and scale innovations that impact poverty at scale.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2022!

Women play important roles in smallholder dairy production. As PxD prepares to roll out a dairy advisory initiative in Kenya, we conducted a gender survey to better understand the division of labor within households. In this post, the second of a two-part series, Sam Strimling, Research Associate, presents an analysis of the results. The first post laid out the importance of understanding the specific needs of women in designing effective service delivery for women.

In many smallholder households, labor relating to the tending of livestock – particularly dairy animal husbandry and dairy production – is derived disproportionately from women. This culturally entrenched division of labor has direct implications for PxD as we expand into supporting dairy farming activities and seek to target our digital advisory services appropriately.

There is a plethora of evidence – much of it detailed in the excellent book, Invisible Women, by Caroline Criado Pérez – of service providers who failed to understand women’s specific needs and preferences and thus designed inferior products. Providers of digital advisory services are no exception to this disappointing phenomenon.

As PxD prepares to roll out a dairy advisory initiative in Kenya, we considered it a top priority to conduct a gender survey to better understand the roles played by each household member with a focus on tasks performed, decision-making, and financial agency. The results of this survey will be used to inform the dairy content we are developing as part of an upcoming randomized controlled trial (RCT) we are implementing in partnership with several dairy cooperatives across different regions in Kenya. We will use the results of the survey to inform the type of content we write, as well as how and to whom we deliver it.

As detailed in a previous blog post about the survey, the PxD Kenya team used a novel and rich dataset to inform survey design. In addition to gaining insights into the roles played by different members of the household, we also sought to better understand the technical and analytical abilities of each respondent, as well as perceived technical knowledge for each household member. Finally, we used methods from behavioral economics to empirically evaluate trust within the household.

Survey Structure

We started with a total sample of 600 households randomly selected from two dairy cooperatives, in the Rift Valley and Eastern regions. The sample was stratified by geography, milk sales to the dairy, and deductions for purchases from the dairy-affiliated agrovet (in which farmers are able to purchase animal medicines and farming inputs using income from milk).

We called 464 unique respondents, of whom 357 answered at least one call. Respondents who lived with or made decisions with their spouses were asked to provide contact information. Single respondents – many of whom were widows or widowers – were encouraged to complete the survey, but were not asked a series of subjective questions about the degree to which they made decisions or discussed activities with their spouses. Single respondents were also not asked to participate in the public goods game. In total, 114 spousal pairs completed the full survey. These spouses, and their respective households, will be the focus of this post. The demographics of the survey respondents and their households are shown in the table below.

Intra-household dairy roles. At the start of the survey, each respondent was asked to list the members of the household above the age of five, and state their age, gender, and education. The survey enumerators used tablets to record responses that allowed them to capture this information to be used later in the survey. Respondents were then asked to select from this list to indicate which member(s) of the household:

- Practiced crop farming, grazing, fetching water, wage employment [Respondents were specifically asked if they held “a job outside the home.”], schoolwork, childcare, and/or leisure in any given week. Respondents were also asked to indicate the number of hours each selected household member spent on each task in a typical day.

- Practiced various dairy tasks, selected from a list of tasks generated by our Staff Dairy Livestock Expert. For each task selected, respondents were asked to indicate which household member took primary responsibility, and how many minutes this individual typically spent on that task per day. This is the only household roster question for which the respondent was asked to select a single respondent rather than having the option to select multiple members.

- Were knowledgeable about nutrition, artificial insemination, hygiene, disease, and feed and fodder. The respondent was also asked to rank the selected household members in terms of their knowledge on that particular topic.

- Had taken various financial actions, including purchased a personal asset, purchased a productive asset, sold crops on behalf of the household, received payment for crops on behalf of the household, received payment for milk production, and made decisions about spending dairy income.

Analytical ability and dairy knowledge. Respondents were asked to answer a series of scenario-based analytical questions as well as questions to assess technical dairy knowledge on a broad range of topics. We then calculated the percentage of analytical and technical questions the respondent answered correctly.

Subjective assessment of financial agency and cooperation. Respondents were also asked to provide information on their personal knowledge and feelings of financial agency. To assess financial agency, respondents were asked to indicate using a Likert scale the degree to which they discussed finances with their spouse, trusted their spouse’s financial decisions, talked with their spouses about agricultural work, and talked with their spouse about their day generally.

Intra-household cooperation – the public goods game. Finally, all respondents who completed the survey were awarded 100 Ksh (approximately $1) in airtime, and – if their corresponding spouse had also completed the survey – they were invited to increase their earnings by contributing some portion of their earnings into a common account with their spouse. Since the amount contributed to this common account was doubled and then split evenly, the respondent’s contribution could be interpreted as an empirical measurement of cooperation with their spouse.

Information asymmetry. For the 115 households in which we collected information from both spouses, we were able to calculate the degree of coherence in their responses in terms of the intra-household (inter-spousal) correlation coefficient.

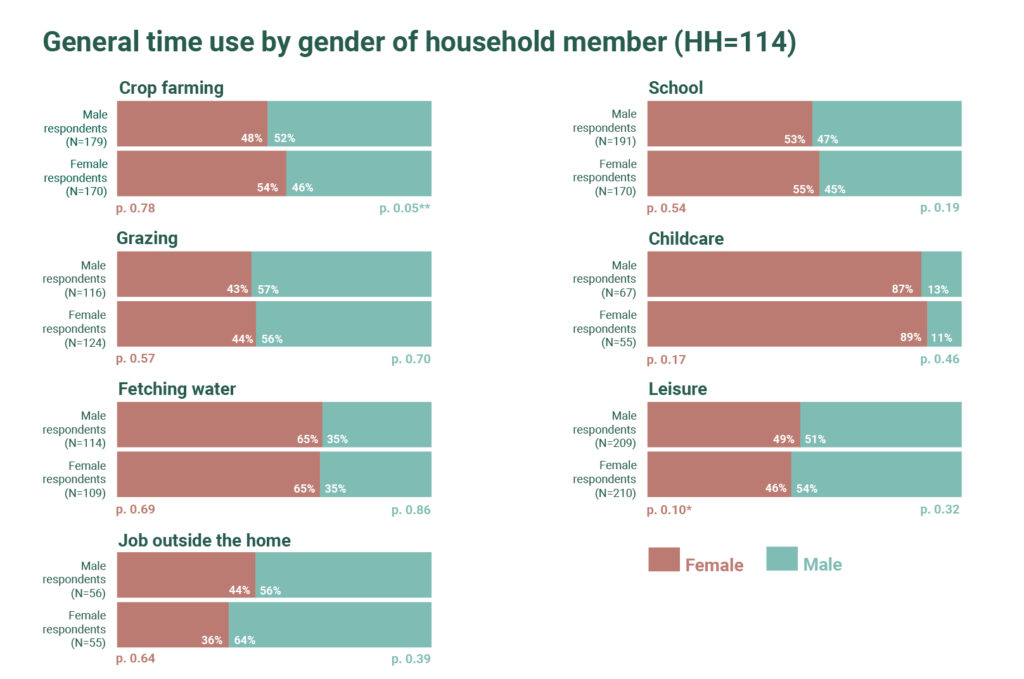

General Time Use & Dairy Tasks

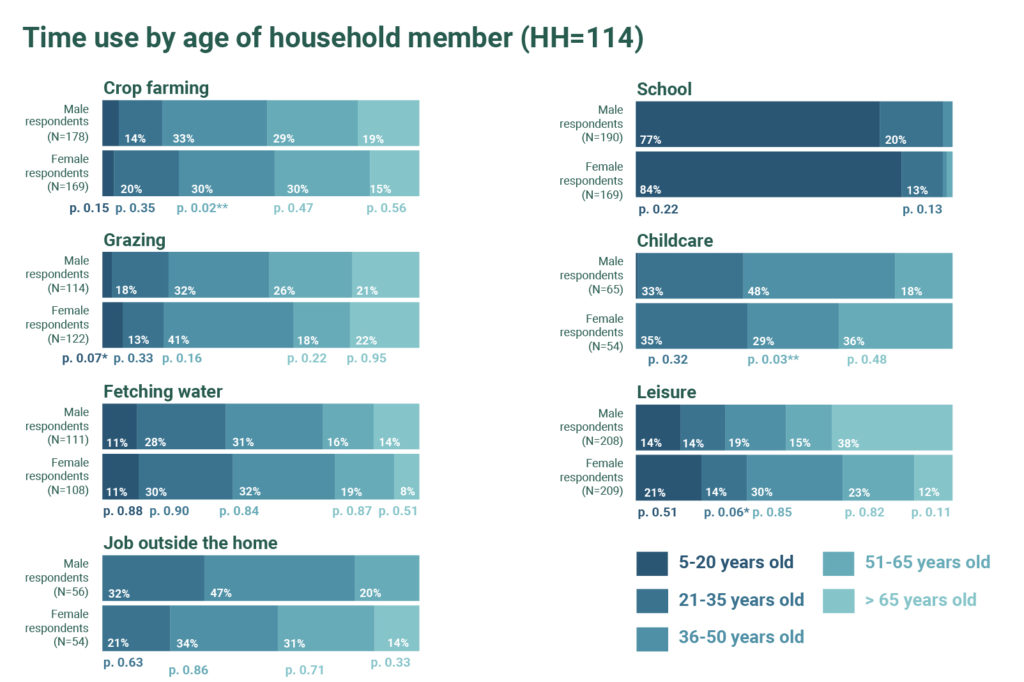

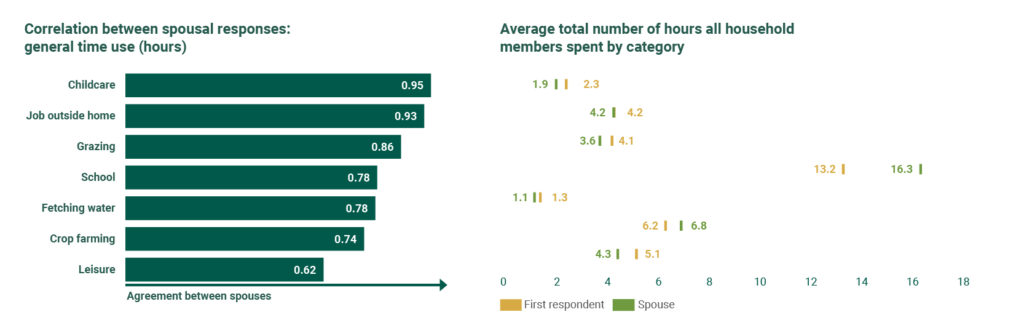

Male and female respondents broadly agreed on the division of labor within the household by gender of household members. We focus our description of intra-household gender-specific roles on the share of time spent by males and females within the household and checked whether men and women respondents generally agree on this proportion. This is presented in Figure 1 below, which organizes respondents’ perceptions by the proportion of hours household members of different genders spend on pre-specified activities within the household (p-values reflect tests of the null that there is no difference in responses across spouses). While male and female respondents differed in their reports of the time spent by gender of the household member, these differences were not significant for any time-use category other than crop farming. In this instance, the difference in perceived hours on task from the perspective of male and female respondents was statistically significant at the 5% level (as demarcated by the p-values next to each bar). In general, respondents of both genders reported that crop farming, grazing, school, and leisure were split nearly evenly by gender. Female household members, however, were reported to spend more time fetching water and engaging in childcare relative to male household members, and male household members were more likely to have a job outside the home.

There was an overall alignment between male and female respondents on the reported activities of different age groups (Figure 2). The overwhelming majority of those in school were aged 5-20, while those aged 26-50 performed the bulk of income-generating labor, including crop farming, tending to grazing animals, and jobs outside the home, as well as tasks culturally associated with “women’s work” (fetching water and childcare). Leisure was fairly equally distributed across age groups.

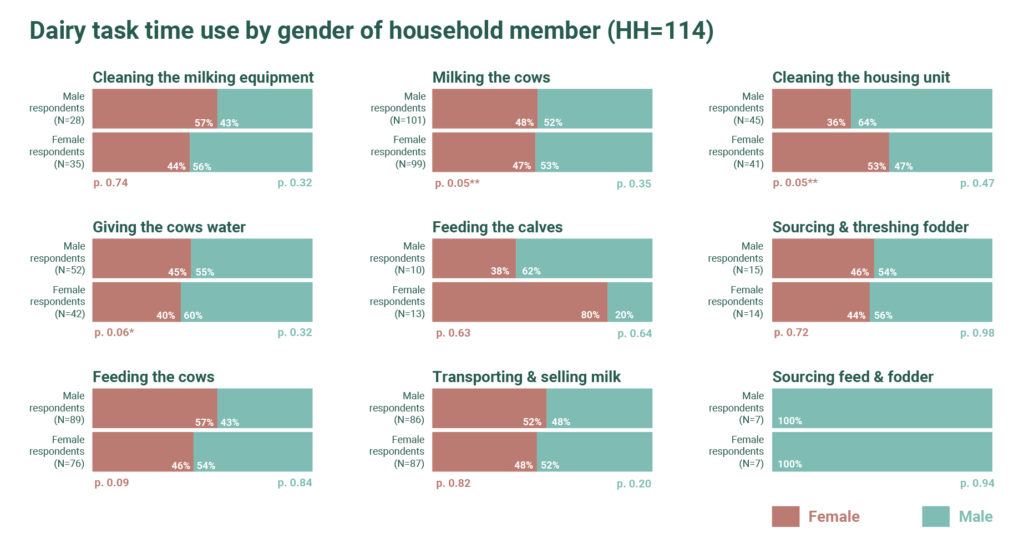

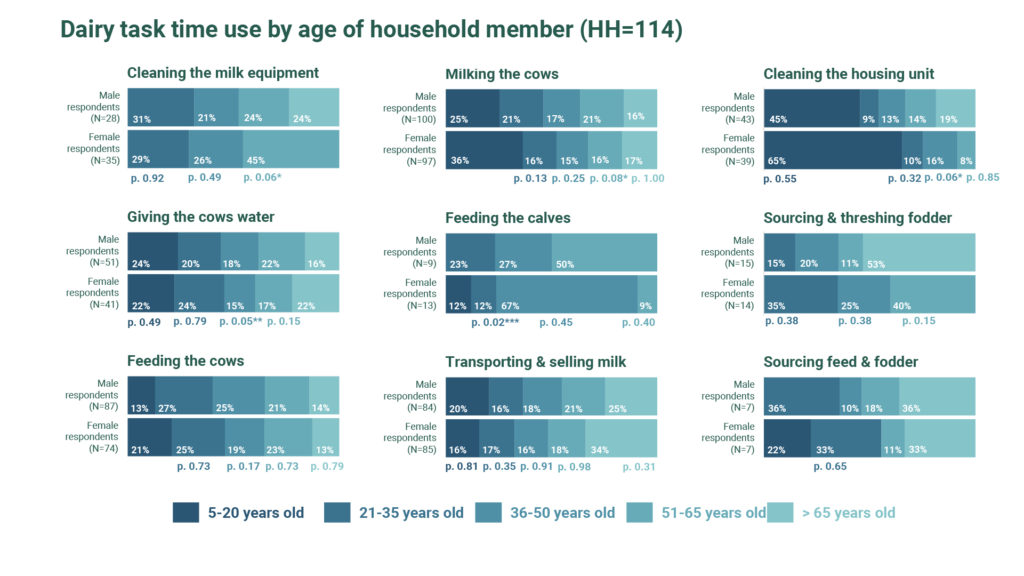

Of the 20 dairy tasks that each respondent was able to select from, nine were selected by respondents in our sample: cleaning the milking equipment, giving the cows water, feeding the cows, milking the cows, feeding the calves, transporting and selling milk, cleaning the housing unit, sourcing and threshing fodder, and sourcing feed and fodder. Figures 3 and 4 below applies the same analysis to these tasks as applied above to the responses on household time use: that is, Figure 3 analyzes the differences in male versus female respondents’ perceptions of household members’ dairy time-use by the gender of the household member, and Figure 4 analyzes this in terms of household member age group.

For most tasks, labor appears to be split fairly evenly by gender. A possible exception to this rule is feeding of calves, which female respondents assert is performed more by women than by men at a ratio of 4:1; men disagree on this, however, which is statistically significant at the 5% level, though the relatively low sample size makes it hard to put too much stock in this comparison. Further analysis could examine whether there is a difference based on a household’s production system. For example, in zero-grazing (or semi-zero-grazing) households, domestic tasks may account for a larger share of household labor, in turn skewing labor allocation toward the purview of women.

In addition to splitting labor by gender, dairy-related labor also appears to be distributed relatively evenly across age groups. The exceptions to this rule are “feeding the calves” and “cleaning the housing unit,” which according to female respondents – but not male respondents – is overwhelmingly performed by younger populations. Though difficult to say conclusively, a possible explanation for this difference in reporting is that female respondents may be more aware of how labor is divided on these tasks, which tend to be domestic in nature.

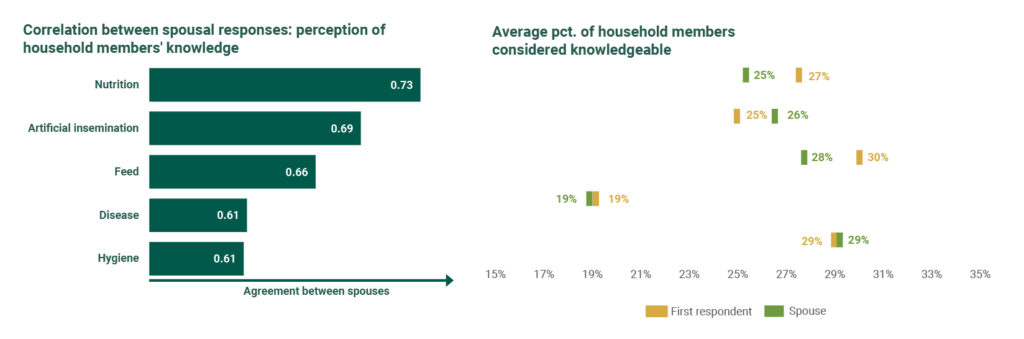

While on average there seems to be a great deal of agreement between spouses in our sample, this does not preclude the possibility of variation in the degree of agreement across households. Figure 5 below displays a measure of within household agreement by calculating the correlation coefficient in the vector of responses provided by women and men respondents in the same household. If, for example, on average, most husband and wife pairs agree on the time spent within the household on childcare, the correlation coefficient will be closer to 1. If they systematically disagree, the correlation coefficient will approach -1. If the correlation coefficient is close to zero, there is no clear agreement between husbands and wives within the same household on how tasks are distributed among household members. In our survey, there was a high degree of correlation between spousal responses for general time-use categories (i.e., crop farming, childcare, leisure, etc.).

Knowledge

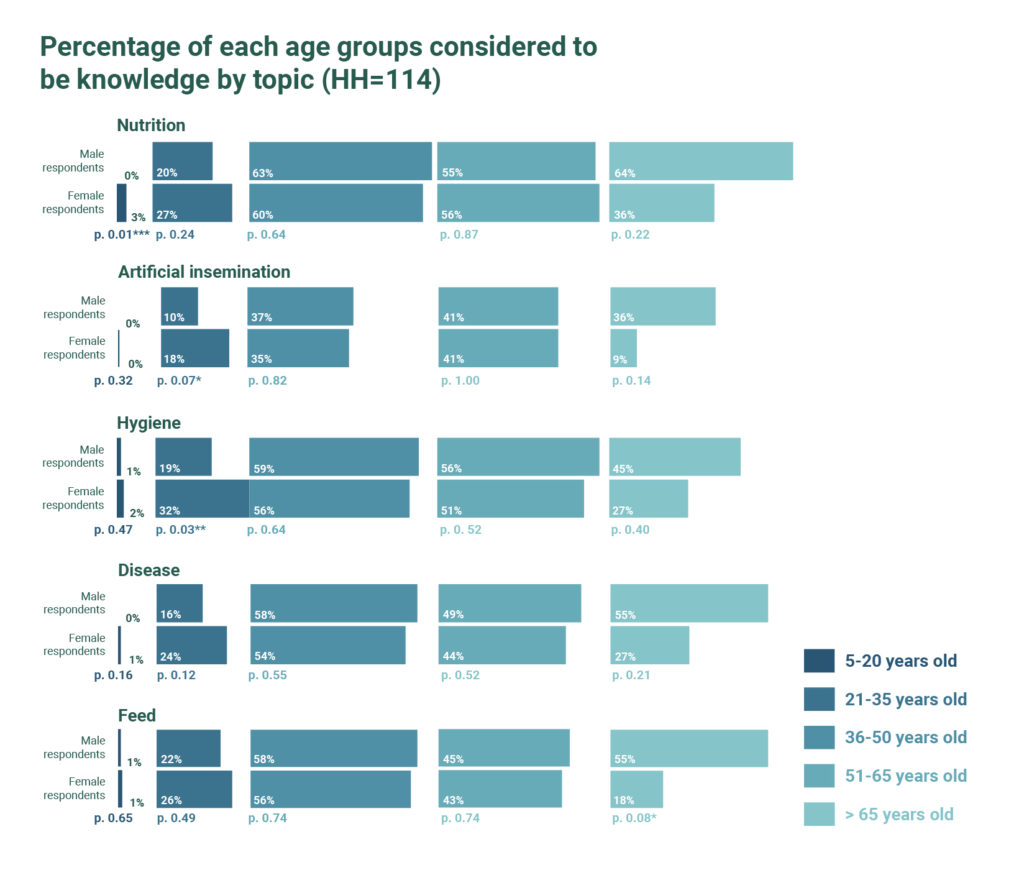

Prior to measuring actual analytical skills and technical knowledge, we asked respondents to subjectively indicate which household members possessed knowledge in five categories: nutrition, artificial insemination, hygiene, disease, and feed. We then calculated the total percentage of individuals within a household perceived to have knowledge on a topic by gender (Figure 6) and age group (Figure 7).

Across all categories, both male and female respondents perceived male household members to be more knowledgeable; there was broad intra-household agreement on knowledge perceptions as well (see Figure 8). Interestingly, male household members were judged to be especially knowledgeable in categories such as disease and artificial insemination; this was particularly true in the eyes of male respondents, who judged male household members to be at least twice as knowledgeable as women about these subjects. One hypothesis for this is that these subjects may carry a connotation of expertise due to their affiliation with actual professionals (i.e. veterinarians). By contrast, the perceived knowledge gap was a lot lower for other categories, such as nutrition and hygiene.

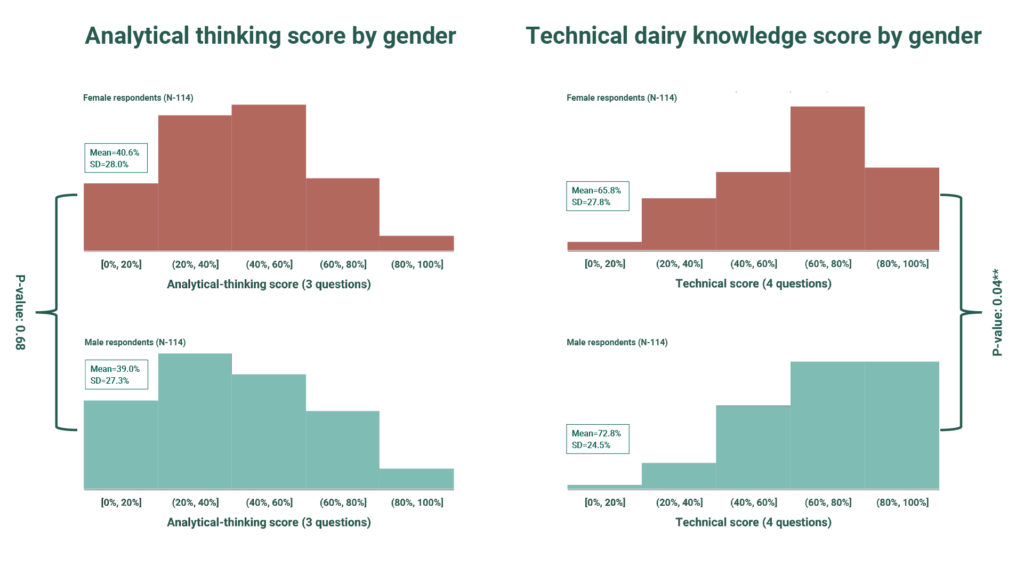

In fact, when tested, male respondents did perform significantly better than female respondents in terms of technical knowledge, with a mean score seven percentage points higher. That said, male respondents performed no better than female respondents on a test that used scenario-based questions to measure analytical thinking.

That said, two caveats must be considered in drawing conclusions from these results (shown in Figure 9): First, these results measure respondent knowledge rather than directly evaluating the knowledge of all household members. Second, the tests were brief and covered a broad array of subjects, making it impossible to evaluate whether the respondent may have deep knowledge on a particular topic. Both of these gaps suggest promising areas for future research in order to better understand the degree to which perceptions of knowledge match reality, rather than merely reflecting cultural biases; in reality, the answer may well be both, though additional empirical analysis is needed to make this claim.

Financial Agency, Intra-Household Decision-Making, and Trust

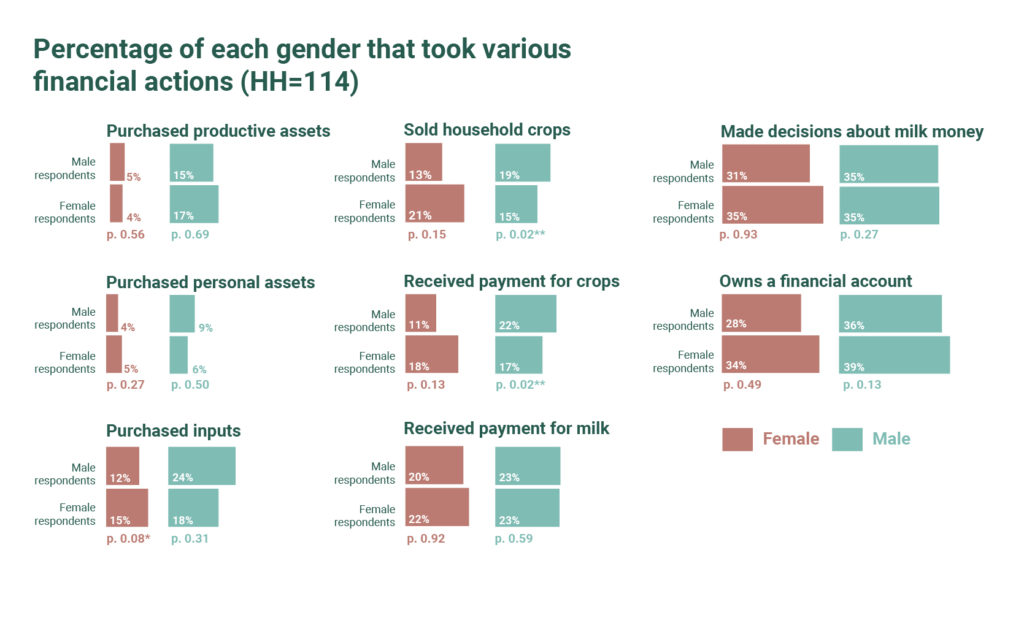

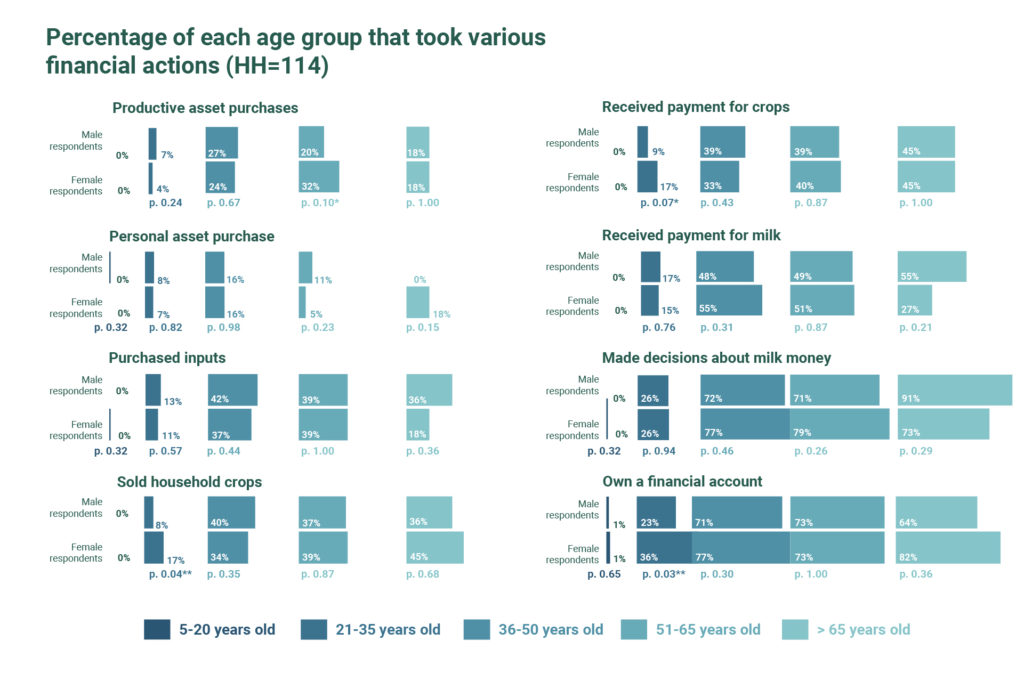

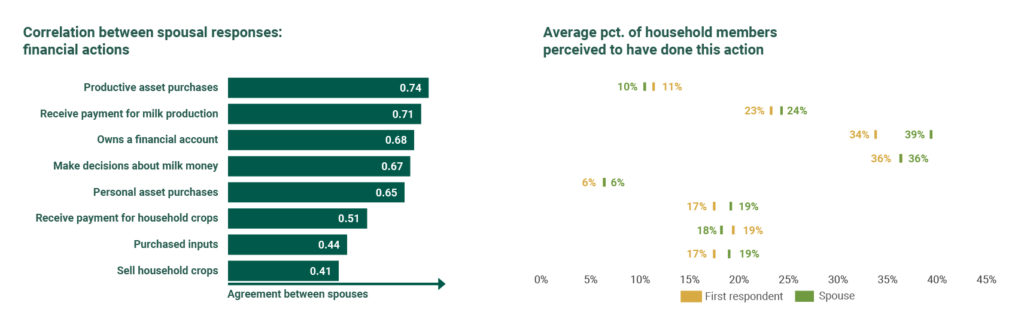

Respondents were asked a series of questions regarding their perceptions about who controlled money within the household: who in the household purchased productive assets, purchased personal assets, purchased inputs, sold household crops, received payments for crops, received payments for milk money, made decisions about spending milk money, and owned a financial account. Figures 10 and 11, respectively, analyze these results by gender and age of the household members.

Very few household members were reported to have purchased personal assets; more – overwhelmingly men – purchased productive assets, according to both male and female respondents. Male and female respondents also agreed that payment for milk money and decisions about milk money were generally split evenly within the household. Both male and female respondents also reported that household members of both genders owned financial accounts (though men did so to a slightly higher degree).

There was less agreement by respondent gender about crop farming. Male respondents reported that male household members played a larger role in selling crops, whereas female respondents reported the opposite. This same pattern was true regarding respondent perceptions of who received payment for crops. In both cases, the difference in the perception of different genders was statistically significant at the 5% level. Additionally, while respondents of both genders agreed that more male household members purchase inputs than female household members, male respondents reported the ratio to be 2:1, while female respondents reported this difference to be marginal; this disagreement was weakly statistically significant (at the 10% level). Within households, there was also comparatively more disagreement on the measures related to crop farming and associated income, as shown in Figure 12.

There are several potential explanations for the disagreement on this measure. One potential reason is there may be an internal lack of clarity within the household about who performed which category of tasks. This does not necessarily mean that individual tasks do not have a “clear” owner; alternatively, the divisions we at PxD made for the purposes of this survey may not correspond to household constructs around the division of finances. This suggests a possible area for future research: an open-ended survey consisting of structured interviews on this topic may yield interesting insights regarding financial accountability and power within the household.

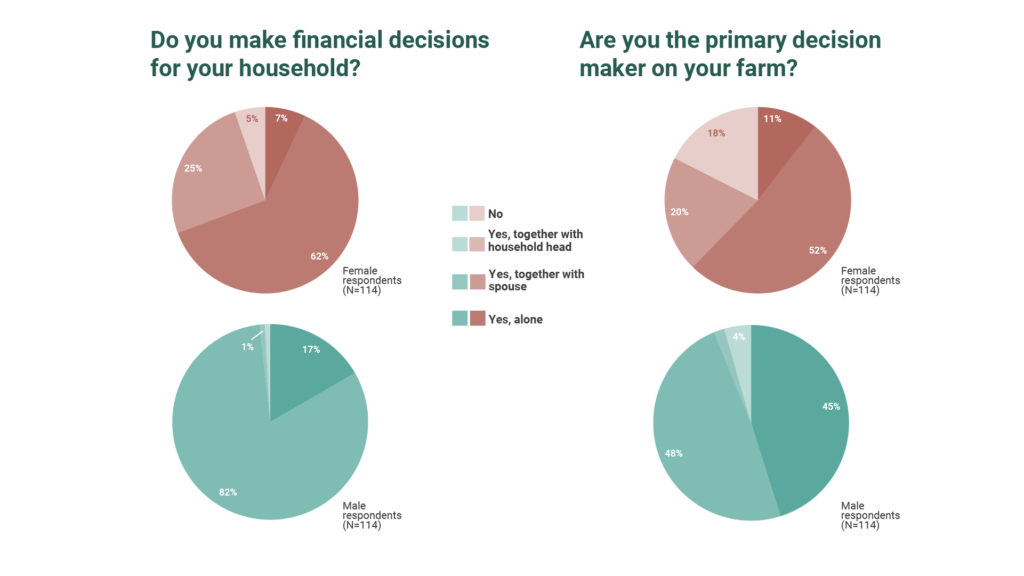

Moreover, the disagreement may reflect the fact that some tasks may be performed jointly (or in an alternating fashion) with other household members; this possibility need not be mutually exclusive with alternative divisions of labor within the household. The results in Figure 13 suggest this possibility. When asked who makes financial decisions about the farm, the majority of women (62%) and men (82%) said they made this decision together with their spouse; an additional 25% of women said they did so jointly with the household head. Even who the “primary” decision-maker was could be muddled, with 72% of women and 50% of men claiming to occupy this role jointly with either a spouse or household head.

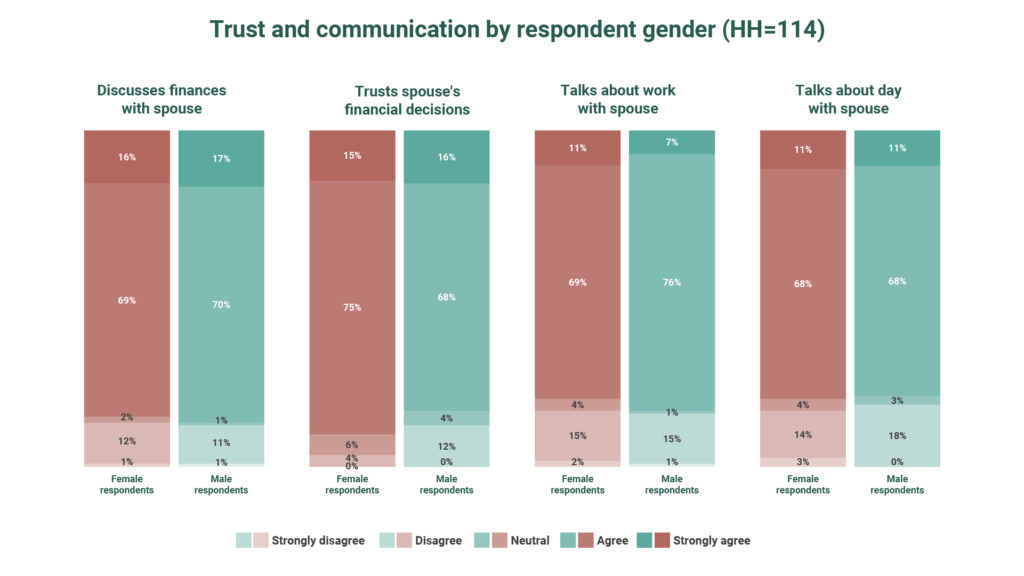

These results are ambiguous regarding whether each decision is made jointly or whether men and women have different spheres of influence within the household (and financial discretion within those spheres). However, the Likert scale questions, in which respondents were asked to agree or disagree with a number of statements about intra-household decision-making suggest that many decisions are made jointly – or at least with a substantial discussion between household members. (Figure 14)

Eighty-five percent of female respondents and 87% of male respondents reported that they discussed finances with their spouse; moreover, 90% of female respondents and 84% of male respondents reported that they trusted their spouse’s financial decisions.

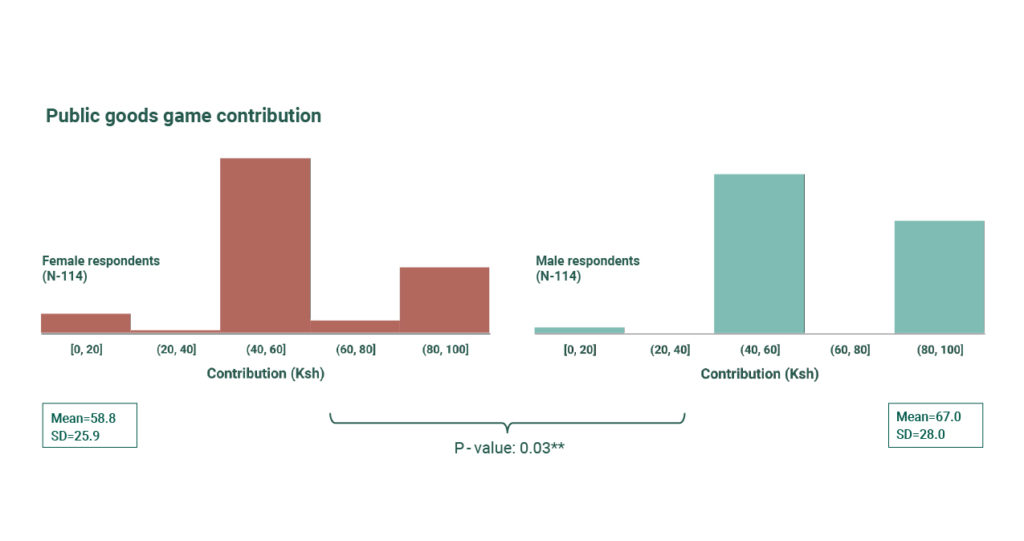

In order to empirically test these subjective responses, we also asked respondents to participate in a “public goods game,” in which they could choose to augment a portion of the financial incentive they earned for completing the survey (100 Ksh, or about 1USD) to a common account. Contributing a greater amount theoretically indicates a greater degree of cooperation with one’s spouse since the amount in the common account was split evenly between spouses after both completed the exercise, regardless of how much each spouse contributed individually. The results of this game suggest a moderate amount of trust, with contributions for both women and men clustering around the midpoint of the range between zero and the total possible contribution. Figure 15 displays the distribution of these respondents’ contributions. While male respondents contributed more on average (statistically significant at the 5% level), the plurality of respondents of both gender contributed a medium amount (i.e., 40-80 Ksh)

One way to empirically evaluate whether the public goods game in practice aligns with subjective cooperation in the household is to directly compare these results. First, we regressed the correlation coefficient between the spouse’s individual Likert responses – that is, the degree to which husband and wife agreed about their level of trust or communication – on the various contribution categories (limited the covariates to the bottom quadrant of Figure 16, to make sure each category reflects a sufficient sample of people to draw meaningful conclusions). The results of this regression are shown in Table 2. There was not a high correlation between these metrics, with none of the contribution categories predicting agreement between the spouses regarding the degree of cooperation.

The next stage of analysis was to compare directly the responses to the Likert scale questions on intra-household communication and trust to the public goods game contributions. To do so, we first split the sample by respondent gender and then ran ordered logit regressions separately for each sample (Table 3). In these regressions, a positive coefficient signifies that a member of a household in that specific contribution category is more likely to “strongly agree” with the statement. To make this concrete, the variable “female mid, male high” in the female sample is equal to one for a member of that population who contributed a medium amount (40-80 Ksh) and whose husband contributed a high amount (80-100 Ksh), and is equal to zero otherwise. A positive coefficient on this variable means that a respondent in this category is more likely to “strongly agree” with an affirmative statement on the Likert response; e.g. for the first regression in the table, she is more likely to say she often discusses finances with her spouse. While all the coefficients for the regressions on the male sample and about half of the coefficient for the regressions on the female sample are positive, none of the results in either sample are statistically significant.

Since the public goods game contributions do not align with subjective measures of intrahousehold cooperation, it is unclear whether respondents are less trusting in practice than they aspirationally report to be on the subjective questions, or whether the public goods game does not accurately measure intrahousehold trust. The answer may be a combination of the two or may vary by Likert category. This suggests an area for future research.

Next Steps

This information is valuable for informing the design and operation of a dairy service that empowers rather than further marginalizes female farmers. It bears mentioning that we will continue to monitor engagement by gender to validate the insights of this survey on an ongoing basis and to make sure that we continue to reach women farmers.

That said, there are a few points we can take away from this dataset –

and we can use it to identify areas for additional research:

- In general, women and men reported that they split labor related to crop farming and grazing, and both females and males reported going to school and pursuing leisure activities. Unsurprisingly, women reported spending more time fetching water and engaging in childcare relative to men, and men were more likely to have a job outside the home. Perhaps more surprisingly, most dairy tasks were split relatively evenly by gender. Further research could investigate the ways different production systems influence household division of labor: for example, since women generally take charge of more domestic tasks, in zero-grazing households is dairy-related labor more commonly performed by women?

- Both men and women perceived men to be more knowledgeable on all topics asked about (nutrition, hygiene, artificial insemination, and feed). One positive of digital advisory compared to traditional in-person systems is that both women and men are able to read the advice on their own, and thus may be less subjected to the influence (and doubts) of peers and other household members. However, this knowledge gap may have implications for marketing: if women are systematically viewed as less knowledgeable, men may find a service that aims to disrupt that balance in the household to be threatening. Additionally, the perceived knowledge gap may pose a barrier to adoption of recommendations by women if proposed without male buy-in and perceived to not know what they are talking about.

- The allocation of financial power in the household was far from clear-cut. A similar proportion of both genders received payment for and made decisions regarding milk money, and respondents of each gender disagreed as a group about which gender sold and received payment for crops. Additionally, the majority of respondents of both genders reported making financial decisions and being a “primary decision-maker” – either individually or jointly with a spouse or household head. Finally, both male and female respondents reported discussing finances with their spouse and trusting their spouse’s financial decisions. While this has positive implications for adoption of advice by both genders, it also suggests that many decisions are made jointly and buy-in from both spouses is necessary for implementation.

- The responses of respondents of both genders to the Likert scale questions suggest a high level of intra-household communication, trust, and cooperation, at least in the subjective opinions of respondents. Similarly, the vast majority of respondents of both genders contributed at least a medium amount (40 out of a possible 100 Ksh) to the common account in the public goods game. This has positive implications for adopting recommendations, which in many cases will require collective household buy-in. That said, there remains opportunity for a more granular understanding of intra-household cooperation. For example, how does it differ in households with more defined household and/or farming roles, or in households where one spouse is clearly knowledgeable? (While this dataset contains questions to this effect, the sample size is too small to draw meaningful conclusions about precise subsets of respondents.) Outside of this data, what impact do production systems (i.e. zero-grazing) and use of particular technologies (e.g. machinery such as chaff cutters or other equipment, such as durable water tanks) have on the level of intra-household cooperation?

While the effort to better understand our service users is ongoing and our efforts to improve content and delivery are constantly evolving, this data collection yielded meaningful insights and constituted a significant step towards inclusive product and service design that can be put to use in PxD’s Kenyan dairy service – and more broadly in programming across the region.

Tomoko Harigaya, PxD’s Chief Economist and Director of Research, reflects on the work of the 2021 Nobel Prize winners in Economic Sciences, and how their contributions to the field have informed PxD’s research practice.

Last week, Jonathan Faull, our Director of Communications, sent me a WhatsApp message: “I had a dream that Owen [PxD’s CEO] woke me up with a phone call to tell me Michael [Kremer] won the Nobel again…”. I laughed and responded saying that he was working too much.

Jonathan’s dream didn’t become a reality, but it wasn’t too far off in spirit. I woke up on Monday, thrilled to learn that the three empirical economists, David Card, Josh Angrist, and Guido Imbens, had won the [deep breath] 2021 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. As per the Royal Swedish Academy of Science’s press statement, Card won the prize “for his empirical contributions to labour economics”; Angrist and Imbens won “for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships”.