Dairy farmers in Kenya are being hit hard by climate change.

The country is seeing increased droughts, and, with dry spells projected to increase up to 27% in severity and heat waves likely to increase in duration by up to 30 days, climate change will continue to exacerbate the multitude of challenges farmers and their families face.

Access to water is key for dairy farmers and is a significant challenge in Kenya, especially in rural areas where the majority of the population lives. 76% of households in rural areas do not have piped water access, and spend an average of 3.5 hours per week fetching water (KIHBS 2018).

Continuous access to clean water is vital for dairy production, with an adult healthy dairy animal requiring about 75 liters of water daily, animals can die without water in 2-3 days. Increased herd movement to water sources impacts cow health and also imposes a substantial time burden, particularly for women and girls, with negative consequences such as dropping out of school.

With changing weather patterns and unpredictable rainfall, rainwater harvesting can provide a sustainable source of water for agriculture and livestock production. This is particularly important in dairy farming, as water scarcity and poor-quality water can lead to decreased milk production and health issues in dairy animals. Large water tanks are an efficient method for storing harvested rainwater.

However, financial constraints limit smallholder farmers’ ability to invest in rainwater harvesting tanks for climate adaptation and improved dairy productivity. Lack of access to credit, limited financial resources, and competing household expenses are major barriers to investing in water storage tanks.

Against this backdrop, PxD’s program on Asset Collateralized Loans (ACLs) for water tanks presents innovative financing mechanisms to address water scarcity and liquidity bottlenecks to improve climate resilience and dairy productivity in developing countries.

How dairy ACL works

Water tanks pose a unique financing opportunity. They are large and difficult to move, and they retain their market value over time, meaning the assets themselves can serve as the collateral for a loan.

This removes the need for guarantors, which often poses a significant barrier to access to credit. Repayment is made automatically from the milk income earned through milk sales from the farmers throughout the month. If the farmer was to default on the loan, the tank could be resold at close to the original value.

About 1.8 million smallholder farmers depend on dairy farming for their livelihoods in Kenya but a bulk of them are unable to obtain loans from traditional lenders, such as banks, because they do not have the collateral or credit history required.

The ACL approach, therefore, has several advantages over traditional lending methods, which often require extensive paperwork and collateral that many smallholder farmers do not have.

Our Research Project

PxD has been implementing a two-year research project on ACLs for water tanks in collaboration with the University of Chicago’s Development Innovation Lab (DIL) and two dairy cooperatives (Lessos and Sirikwa Dairies) in Kenya’s Rift Valley region.

A previous study (Jack et al., 2019) demonstrated strong evidence that the ACL model for water tanks could improve farming and household health, as well as well-being outcomes among smallholder dairy farmers.

The study, conducted in partnership with the Nyala Savings and Credit Co-Operative Society (SACCO), randomly offered some farmers the opportunity to replace loans with high down payments and stringent guarantor requirements with loans collateralized by the asset itself.

At the end of the study, default rates were extremely low (less than 1%). Milk sales to the cooperative increased by 6-10%. And, because of the increased water supply within households, girls spent 19% less time fetching water, and school dropout for girls decreased by 85%.

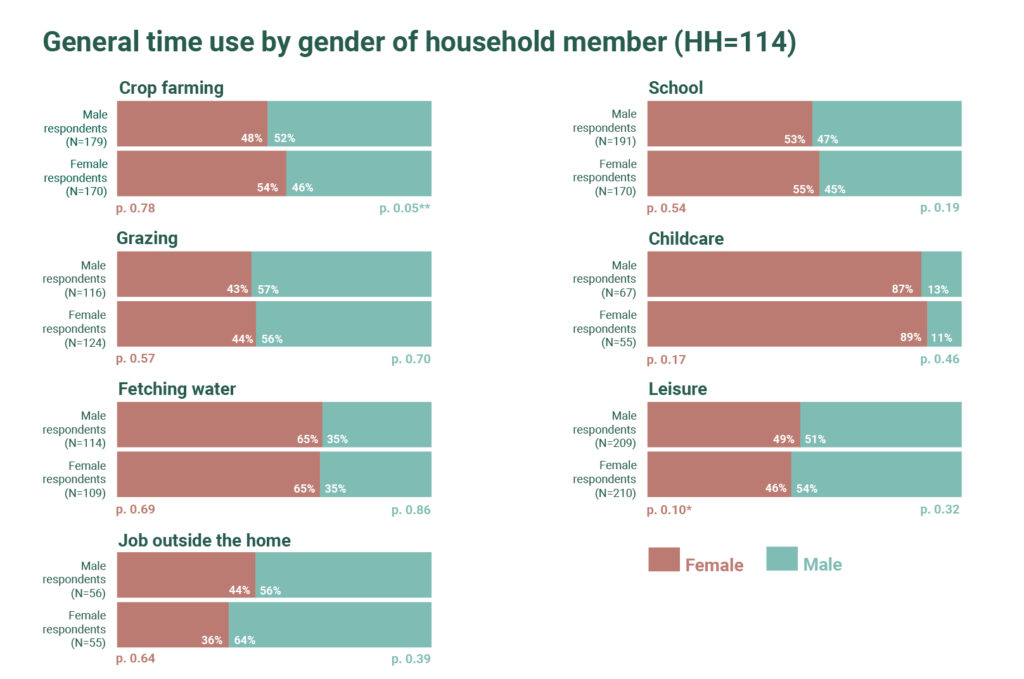

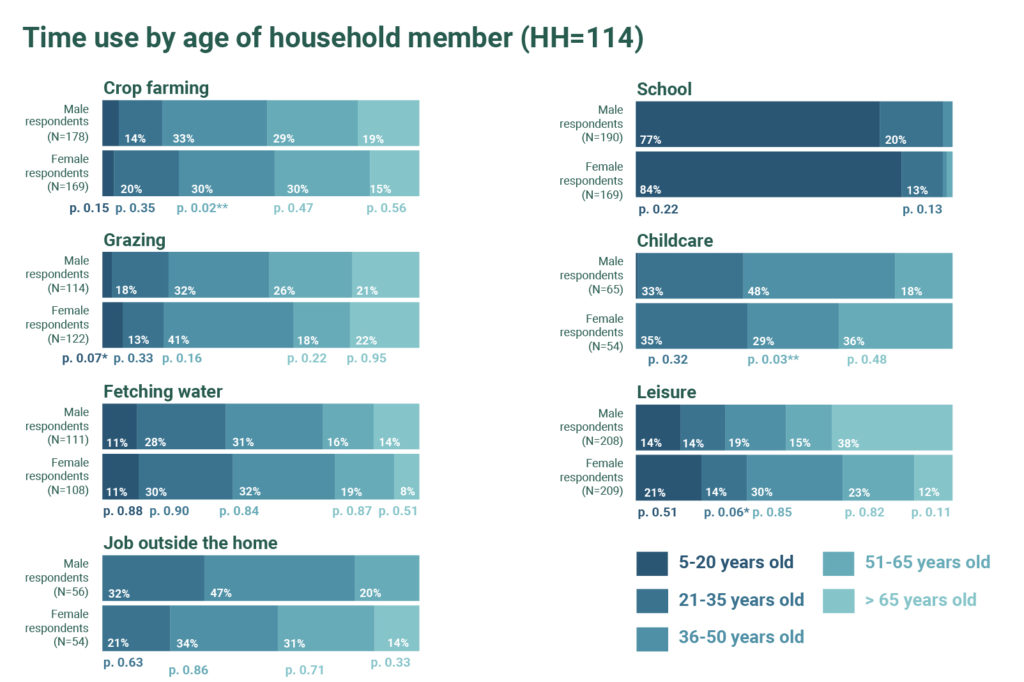

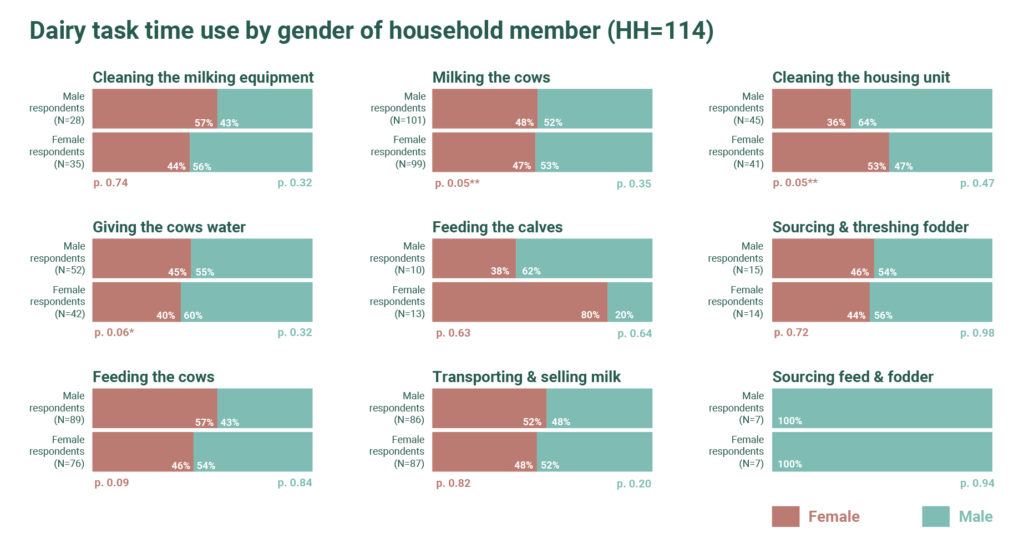

This new study aims to evaluate the impact of ACLs for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. The main outcomes of interest include milk production and milk sales, loan performance, dairy farming practices, water use, time use (particularly for girls and women), household welfare, and well-being.

Delivering tanks to farmers

In partnership with the dairy cooperatives, PxD identified farmers that are eligible to receive the water tanks.

Eligible farmers need to pay an upfront deposit (currently 20%) to receive the tank, followed by monthly loan repayments over a two-year period. Farmers can choose between a 2500-liter or a 5000-liter tank depending on their needs. They receive the tanks at their doorstep for free, with a water tap that is ready to install. Starting from January 2023, PxD rolled out the tanks to a small group of 100 farmers. As of mid-March, 15 farmers had received the tank.

Farmers like Philip Too, a farmer from Sirikwa Dairy who has four dairy cows. Most of the people in his village rely on wells for their household water needs but unfortunately, they do not have sufficient water storage equipment. He is one of the few lucky farmers who are connected to electricity and thus he intends to fill his tank with water from a well within his farm using an electric water pump. With the tank, he hopes to have enough water to not only meet domestic needs for his family and livestock but also irrigate his small kitchen garden from which he expects to fetch some income by selling surplus vegetables to his neighbors.

Esther Sambai, a farmer from Sirikwa dairy, decided to get a 5000-liter capacity tank instead of a 2500-liter tank to meet the needs of her household and neighbors. She said, “My well does not dry up and many people in my village get water from my household for free in the morning when I am at home. As you can see, we pump water directly from the well and therefore I decided to get a bigger tank so that I can store enough water for my family and neighbors. With a tank, my neighbors will be able to access water even when I am away. I will also use the tank to supply water to my animals.” Esther has a solar-powered pump but before the ACL for water tanks, she did not have a water storage tank. The ACL has enabled her to finance a tank easily.

Way Forward

In the coming months, we plan to roll out the tanks to additional farmers (with the goal of reaching 750 farmers in total).

From our early interactions, we have learned that several factors influence take-up including time of the year, competing financial needs such as school fees, and low trust in new financial products which could limit farmers’ take-up of the product.

To address this, we hope to pilot low-risk ways of making the ACLs for water tanks more accessible, such as by lowering the deposit or offering a grace period. We will continue to test similar loan flexibility mechanisms until we can define a product that is interesting, safe, and accessible to farmers across contexts and geographies.

PxD is also making its first foray in Kenya into using low-power radio communications for remote sensing by experimenting with water sensors in this study. These sensors will allow us to measure real-time water levels for dairy farmers so that we can correlate supply, consumption, and dairy output. We hope this paves the way for us to explore the use of other sensors (such as those that measure soil moisture or air quality) to improve farmers’ access to real-time information.

Our first few months of rolling out water tanks have given us insight into the potential for ACLs to enhance credit access for productive assets by reducing the financial burden and collateral obligation that smallholder farmers typically face.

We believe this initiative can have a profound impact on farmers and their families in different contexts struggling with access to water, and could be a path not only to increase profits for farmers and the welfare of their livestock, but improve the well-being of women and girls who are those being most impacted by climate change.

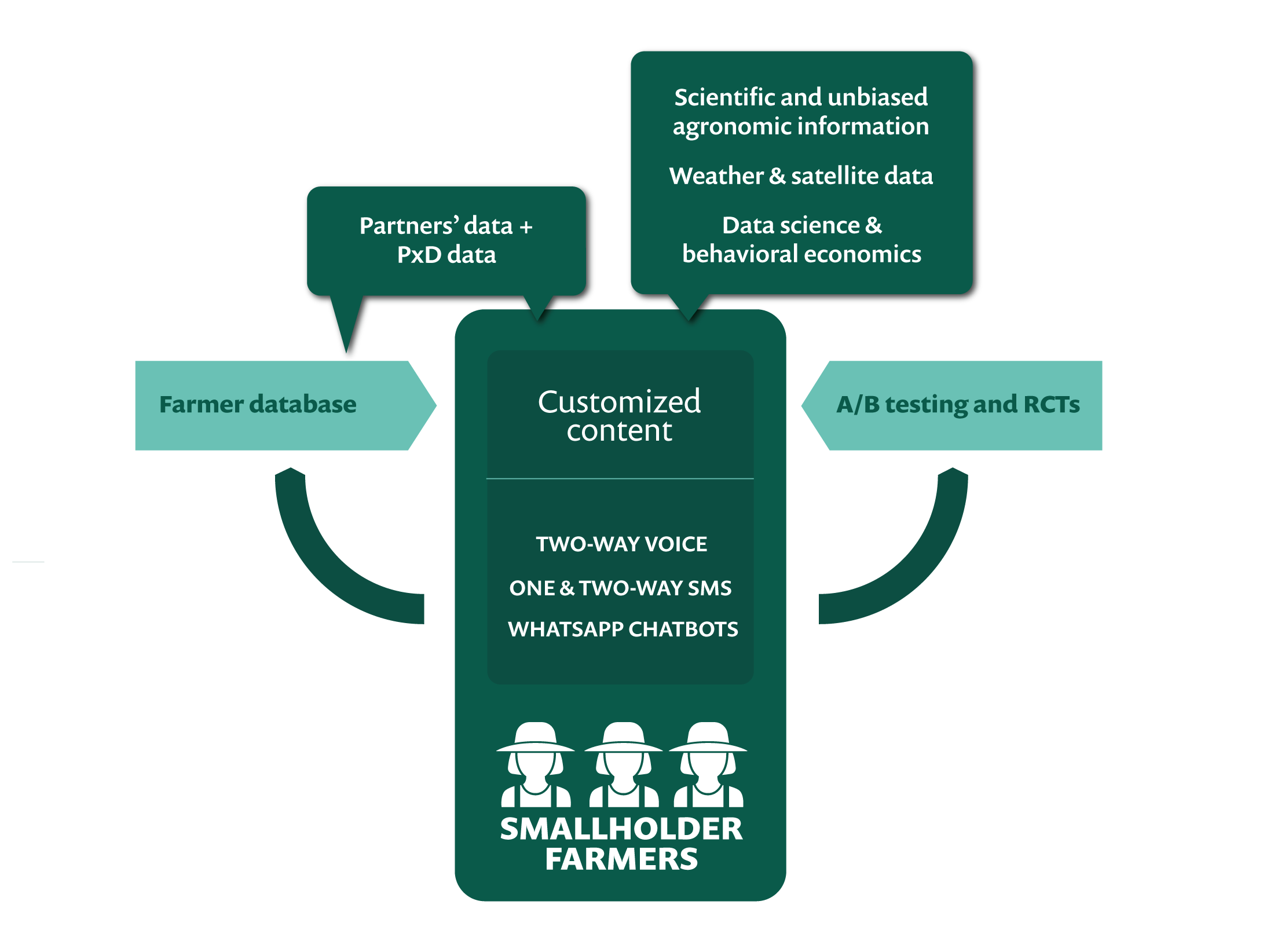

2022 was a tremendous leap forward for research at PxD. Our research and operations teams completed a total of eight A/B test experiments and impact evaluations. We collected data in person and over the phone from approximately 20,000 survey respondents in 27 distinct surveys that took place in Kenya, Ethiopia, Colombia, Pakistan, and three states in India.

We generated new insights to build future programming such as an SMS agro-dealer directory to reduce input market information frictions, built evidence-based proofs of concepts for innovative service design such as WhatsApp-based crowdsourcing chatbot and learned to leverage research partnerships for scalability with dairy cooperatives. We used research insights to shift and refine our approach and we are excited about further impact evidence from forthcoming analysis in 2023.

Devastating events in 2022 from drought in the Horn of Africa to the 100-year flood in Pakistan emphasize that climate change is one of the most urgent challenges facing our users. As such, we have intensified our research efforts to identify interventions that can improve smallholder livelihoods whilst incorporating climate adaptation and mitigation efforts into our existing services. We’ll continue this innovation research agenda in the coming year to explore high-value innovations to supplement our core digital agricultural advisory.

New insights to build future programming

Across a diverse portfolio of research projects, we have demonstrated the value of PxD’s services and contributed to an expanded knowledge base on digital agricultural extension. A particularly promising finding is establishing that digital tools can be effective in improving in-person extension services.

Performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages could increase extension volunteers’ performance: Through a large-scale randomized evaluation in Rwanda, we demonstrated that performance goal reminders sent via SMS messages – particularly goals that were ambitious but attainable – could improve community extension volunteers’ (known as Farmer Promoters – FPs) performance and therefore generate positive impacts on farmers’ outcomes. Sending goal reminders to FPs significantly increased the number of farmers trained by 3.1 percent, led to a significant 4.3 percent more training sessions being delivered, and increased farmers’ registration for subsidized inputs by 1.9 percent (statistically insignificant) over FPs who did not receive goal reminders. Given that the unit cost for each SMS is $0.006 and the average number of farmers assigned to each of the ~14,000 FPs across Rwanda is 190, the effect sizes of these messages are likely to be highly cost-effective.

The results of the Rwanda project support the expansion and replication of extension agent interventions in other settings targeting different populations in the future. In addition, these results point to areas for future research and development that could enhance the effectiveness of extension agent services. For example, we are interested in exploring how digital tools can be used to help extension agents set performance-increasing goals, direct them to farmers most in need, and extend information access to farmer populations that may not benefit from direct digital advisory services.

A digital directory of agro-dealers has the potential to increase the adoption of recommended inputs: In Kenya, we found evidence that farmers can benefit from the provision of an SMS agro-dealer directory by reducing input market information frictions. Our preliminary empirical findings suggest that – particularly for a directory that includes stock and price information about agro-dealers – access to this tool prompts farmers to refine their choice of agro-dealers before an in-person visit. Farmers in the treatment arm who had access to the agro-dealer directory and stock information contacted 21 percent more agro-dealers, but visited 4 percent fewer agro-dealers relative to the control group which did not have access to the tool. This suggests that farmers in this treatment arm used the contact information to call more agro-dealers before spending time and money to travel to the shops themselves.

Farmers given access to the agro-dealer directory were more likely to purchase PxD-recommended inputs and experienced fewer stockouts than those who didn’t have access to the directory. When pooling the two treatment arms, we observe that consistent with PxD’s advisory recommendations, treated farmers were 6 percent more likely than control farmers to use hermetic bags to store maize – a practice shown in rigorous studies like Ndegwa et al. (2016) to prevent post-harvest losses from pests. Farmers in the treatment arm with access to the directory but not stock info appeared to contact and visit agro-dealers at the same rate as the control group but then were 22 percent less likely than the control group to report facing an input shortage when they shopped (meaning they were more likely to find and purchase the product they were looking for).

Building on these promising findings, we hope to identify opportunities to further develop a scalable digital agro-dealer directory tool. Specifically, we are interested in exploring ways to onboard a large number of agro-dealers and update the stock information at a low cost.

Building proofs of concepts

Digital peer groups increase farmer interactions and potentially increase the adoption of recommended practices, but we need creative ways to form groups at a low cost: Various research projects aimed to demonstrate proof of concept for novel interventions that PxD was exploring for the first time. For example, we now have empirical evidence that an intervention in Kenya to organize farmers into groups and send them SMS nudges to communicate with each other was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members. Treatment farmers who were organized into digital peer groups had higher interaction levels than their control group counterparts and were 43 percent more likely to meet with their group members on a farm than control farmers. Interacting with one’s group members on a farm was also associated with increased adoption and knowledge of recommended practices.

A gig-worker model for crowdsourcing agricultural field photos has the potential to generate real-time data on field conditions: We acquired institutional knowledge, both technical and regulatory, to build and operationalize crowdsourcing platforms to demonstrate the feasibility of crowdsourcing information from agro-dealers and farmers in Gujarat. In a pilot, we set up a WhatsApp chatbot, integrating a WhatsApp Business Account with our in-house user communications platform, Paddy, to guide users through a systematic inspection of a field for crop health issues and send reports back to PxD with their findings.

Eighteen of our recruited farmer agents consistently engaged with the program over 10 weeks, with a median of nine crop health reports per agent. The quality of field reports was high – approximately 94 percent of reports are usable. In total, we received 220 field reports with accurate GPS locations and usable photographs. Each of these reports costs INR 125 (USD 1.67), which is substantially below the cost of a 15-minute phone survey. This suggests that crowdsourced data could be a cost-effective method of collecting local data.

PxD aims to further build this knowledge to crowdsource various types of information and use it to improve future service offerings by customizing advisory to be more locally relevant and actionable.

Working with smallholder farmers in the fight against climate change

We are intensifying our efforts to provide information to smallholder farmers that will allow them to make informed decisions to reduce the risks that climate change presents to their livelihoods and to consider adopting practices that can actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We approach this work with the guiding principle of farmer welfare first: smallholder farmers cannot be expected to pay the price for climate change mitigation. Climate change-related advisory should directly support livelihood gains via improved agricultural output or renumeration .

PxD, in collaboration with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD), worked to assess opportunities to benefit poor farming communities through their participation in climate mitigation activities and to direct tangible returns to participating smallholder communities.

The PxD-IGSD collaboration has focused on exploring four mitigation areas with most promise in agriculture: Carbon dioxide sequestration through enhanced rock weathering; Carbon dioxide sequestration with organic carbon storage in soils and plant biomass; Nitrous oxide mitigation through precision nutrient management; and Methane mitigation in dairy through improved livestock feeding practices.

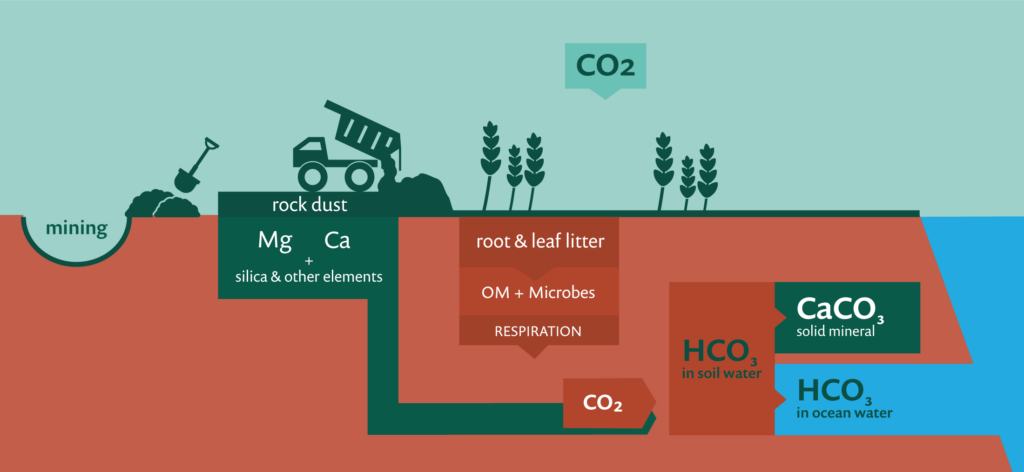

- Enhanced rock weathering (ERW), an emerging technology that permanently draws down carbon from the atmosphere and has the potential for agricultural co-benefits makes it an attractive mitigation strategy in the smallholder farmer context.

- There is evidence that conservation agriculture practices that many farmers are already familiar with – such as reduced tillage, the use of cover crops, and intercropping – promote the sequestration of organic carbon in soils.

- In terms of nitrous oxide emissions, simple decision support tools following the Site Specific Nutrient Management approach, i.e. Leaf Color Charts (LCC), have been shown to reduce nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use as well as improve farmer outcomes.

- For methane, improving feeding practices that increase milk production and closing the dairy yield gap in the Global South per cow can lower the methane intensity of production and contribute to methane mitigation, as well as improving farmer livelihoods.

We’re excited to be on the cutting edge of exploring the potential of these climate change mitigation opportunities- like scoping a digital version of Leaf Color Charts to enable the tool to reach a wider scale and Advanced Market Commitments to incentivize R&D for enhanced rock weathering. Our research initiative with IGSD has enabled PxD to identify future activities within each opportunity area to advance climate change mitigation in the smallholder farmer context and we are actively pursuing partnership and funding opportunities to advance these activities.

Learning to leverage research partnerships for scalability

Partnerships have proven to be a critical pathway to increasing impact and scaling evidence-based programs across our project portfolio.

By collaboratively identifying and developing high-impact opportunities with dairy cooperatives in Kenya, PxD has identified a new partnership model in which PxD serves as a technical and analytical partner for innovating and testing service offerings for cooperatives, and builds cooperatives’ capabilities for generating greater impact at scale. We kicked off the partnerships with Lessos Dairy and Sirikwa Dairy by adapting an asset-collateralized loan product for water tanks which has been shown to dramatically increase access to water tanks among dairy farmers in a research study (Jack et al, 2022) and setting up an evaluation to measure its impact on economic and household outcomes.

In Gujarat, India we surmise that identifying low-cost and scalable approaches to crowdsource pest information will require leveraging local organizations and existing social networks for cost-efficient recruitment and training of agents.

To further explore opportunities to support women farmers in Gujarat, we successfully established partnerships that allow us to better understand the constraints women farmers face in engaging in economic activities and their access to information and other services. These partnerships allow us to design and implement group-based digital services to address those specific constraints.

Insights to shift and refine our approach

Our scoping activities allowed us to identify when a change in approach was needed or when interventions did not turn out to be as promising as we had hoped.

In the dairy sector in Kenya, we learned that existing market and coordination failures, such as credit constraints, need to be addressed to create an environment in which digital advisory can effectively improve smallholder dairy productivity.

In testing social learning mechanisms in Kenya, we did not find evidence that the designed intervention increased farmers’ knowledge or the likelihood of adopting recommended practices, despite finding that peer learning was effective at increasing both engagement with PxD’s service and communication between group members.

While subsequent qualitative interviews suggest that some farmers visited the farm fields of their peers and experimented with the recommended practices in a small portion of their plot, developing the digital peer group advisory further is likely to require a substantial investment in basic research to understand farmers’ social learning process and identify creative ways to reduce the relatively high costs associated with forming peer groups.

Finally, we learned to exercise caution in working with established women’s groups in Gujarat in a way that does not exacerbate local power dynamics within communities to ensure PxD’s services are designed in a sensitive way to promote the inclusion of marginalized groups that may face particularly challenging digital access gaps.

Looking forward to continue building our evidence base

In the coming year we are looking forward to continuing to build our evidence base with forthcoming insights on PxD’s impact on farmer welfare from several large-scale RCTs in India, Uganda, and Kenya.

For the impact evaluation of our largest service offered to date for rice farmers in India, endline data collection and analysis are expected following the second season of implementation in 2023. In addition to outcome data on farmers yields and profits, we’re excited to generate additional insights on scalable measurement options for detecting yield changes among rice farmers using remote sensing data.

In Uganda, our work with coffee farmers enabled PxD to explore several dimensions of digital advisory, including comparing a stand-alone digital advisory service to the provision of digital advisory as a complement to in-person training and studying social spillovers from our advisory services. An endline analysis of the effects of this program will be forthcoming in 2023.

We are also excited to generate initial insights on the impact of asset-collateralized loans for water tanks on economic and household outcomes among dairy farmers in Kenya. Using frequent administrative data from dairy cooperatives on milk production, we’ll be able to understand how improved access to water tanks helps farmers mitigate productivity shocks and domestic water shortages as farmers adapt to more dry spells from a changing climate.

In addition to evaluation research with rigorous RCTs, we look forward to building out our research innovation agenda in the coming year. We are exploring a variety of new, evidence-based high-value product innovations that can build on our agricultural impact for smallholder farmers, such as interventions to facilitate market linkages and access complementary financial services. We are committed to using rigorous evidence and deep user research to identify and prioritize which ideas to pursue.

We look forward to sharing new insights with you throughout 2023! If you’d like to learn more or partner with PxD on specific areas highlighted please get in touch!

Paying people for actions that contribute to climate change mitigation, known as payment for ecosystem services (PES), has the potential to address both environmental and poverty alleviation goals. For example, there is a strong history of PES programs to reverse and slow deforestation in communities in the Global South. Emerging evidence of PES in the agricultural context also shows incentivizing smallholder farmers monetarily can be effective in encouraging behavior change for climate change mitigation.

One way to finance PES programs gaining increasing interest from both the public and private sector is the voluntary carbon market, expected to be worth $50 billion by 2030. Connecting farmers to the amount of climate financing potentially available in the voluntary carbon credit market may help facilitate a sustainable agriculture transformation. However, a key variable still poorly understood is what the value of carbon credit prices should be to appropriately compensate farmers while also achieving carbon removal goals. The low and volatile prices of current nature-based carbon sequestration projects, ranging from $5–$15/ton of carbon from 2021 to 2022, can exacerbate the equity challenges PES programs face, especially in smallholder farmer contexts where ensuring procedural fairness and safeguarding the rights of smallholder farmer communities are critical.

There is currently little transparency into how prices for voluntary carbon market projects are determined, as well as the percentage farmers ultimately receive. As there is no standard system for carbon credit pricing, most pricing is determined between individual buyers and the specific project developer. If the buyer is a corporation that has set an internal carbon price, then there can be a degree of transparency in the price that the buyer is willing to offer for carbon credit projects. However, as the World Bank stated in a report on carbon pricing:

The market for credits from independent crediting mechanisms is heterogeneous, with buyers placing a range of values on characteristics such as the sector (e.g., type of activity), geography, age/vintage, and co-benefits of credits. While recent years have seen some moves toward offering standardized contracts…prices vary widely, with trading platforms offering contracts representing credits from different sectors.

There are also few voluntary carbon market projects available right now which involve smallholder farmers, which makes assessing the true price potential of these types of projects difficult.

Yet, the market is developing rapidly and the long-term vision for the sector will be to ensure standard processes (i.e. contracts, measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of climate change mitigation outcomes, etc) exist so buyers are certain of the carbon removals they are purchasing and the supply of carbon credit projects consists primarily of those for which carbon removals can be verified. The combination of the two will help ensure higher voluntary carbon credit credits in the future and any smallholder farming communities involved are appropriately compensated. A Bloomberg report estimates in a scenario where only verified carbon removals are allowed in the carbon market supply, “prices shoot up to $224/ton” by 2029.

There is another side to having prices this high, as the same report states that under this high price scenario, carbon credits may be seen as too expensive and be regarded as a “niche, luxury product” that few buyers can afford. However, while we may not want to be in a world where carbon credit prices are in the hundreds of dollars, it is clear there are fixable market failures in the current voluntary carbon market – information costs and transaction costs – which prevent smallholder farmers from getting full value for emissions reductions.

The Science Based Targets Initiative and the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative are examples of organizations working to advance rigor, transparency, and standardization in the voluntary carbon credit market. Higher and more stable prices will strengthen the power of the voluntary carbon credit market to provide equitable payments for ecosystem services programs for smallholder farmer behavior change.

Achieving such prices will require investment in the standard market process mentioned above which will improve the credibility and verifiability of carbon credit projects as well as make the voluntary carbon market a realistic pathway for smallholder farmers to increase their incomes by participating in carbon removals.

PxD published an analysis of the opportunities for smallholder farmers to drawdown of carbon which discusses both the evidence for such strategies (including conservation agriculture practices, agroforestry, and biochar) and the barriers to widespread implementation. We aim to leverage our scale – PxD services reached over seven million farmers in nine geographies last year – to continue to explore ways for farmers to engage in voluntary carbon credit markets and push for market developments which facilitate their participation. We welcome connections with organizations and funders who are also interested in such work so we may work together to improve both livelihoods and protect our planet.

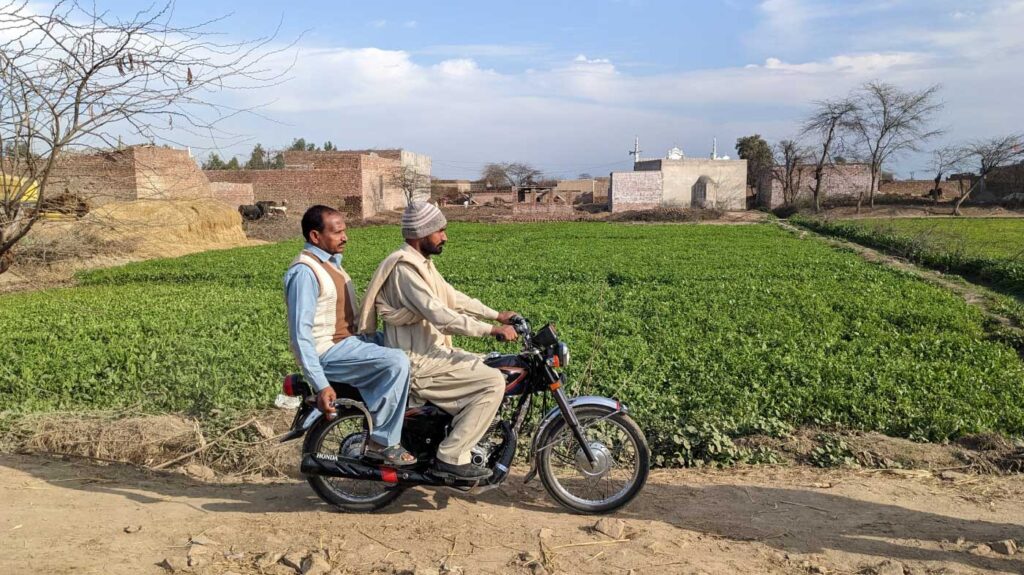

Punjab means “five rivers”, and those five rivers are the reason that the Punjab region in Pakistan is the country’s bread basket. Tomoko and I were in Punjab last week visiting the PxD Pakistan country team. As many of you will know, PxD in Pakistan is housed within a local economics research institute, CERP, a partnership that has enabled us to be more effective and flexible.

This week much of our attention has been on smallholder rice production. The staple food in Pakistan is of course wheat (for roti), but rice is a major crop for both domestic consumption and export. (We were in town at the same time as the IMF delegation, negotiating a package of macroeconomic reforms to stabilise the economy, so those export earnings are important right now).

Punjab is famous for its basmati rice, a variety much prized for its aroma, fluffiness and grain length. It is very popular in traditional dishes like biryani and pulau. We visited Kala Shah Kaku Rice Research Institute, established in 1926, where basmati rice varieties have been developed since the 1930s. Farmers in Pakistan typically grow wheat in the Rabi season and then many grow rice in the Kharif season, especially in the basmati belt in Punjab. The yield of basmati rice is around half as much per hectare as hybrid rice varieties, but it sells for around twice the price, so generating similar revenues and broadly similar net income per hectare. (An exciting development on the horizon is the prospect of hybrid basmati rice that may have a much higher yield while retaining much of the quality for which basmati rice is famous.)

Many of the people we met were keen to stress that Pakistan, rather than India, is the home of basmati rice. I’d be very glad if the rivalry between these two great nations were confined to arguing about the origin of basmati rice and, far more importantly, their relative prowess in cricket.

Pakistan’s farmers produce on average around 4 tonnes of rice per hectare, about the same as in India. In China, the yield is 7 tonnes per hectare and in Australia 10 tonnes per hectare. The yield gap (that is, the gap between what farmers produce and what they could produce with the land and other inputs available to them) is estimated to be about 50% – about 3.5 tonnes per hectare – for basmati rice, and closer to 60% – 6 tonnes per hectare – for the higher yield but lower price varieties. In other words, farmers could, in principle, at least double their yields. So what is holding them back?

You would expect farmers to be more interested in increasing their profit than their yield, so one possible explanation – in theory – could be that the additional inputs are too costly, and the value of the extra output does not justify the investment. In that case, it would be rational for farmers not to increase their output this way. But that doesn’t seem to be the problem. The additional cost of the recommended inputs, at market prices, is small relative to the price that basmati farmers could get for the roughly extra 3-4 tonnes per hectare that they could be producing. Despite extra input costs, the extra yield on this scale would lead to much higher profits – perhaps multiples of profits now being earned. If you are doing only a little better than breaking even, then moving to a reasonable surplus could mean a transformational increase in net income.

So what is getting in the way? We spent two days in villages outside Lahore talking to farmers, extension agents, and private and public sector experts to try to get a better picture.

My main take-away is that it seems that expensive credit for agricultural inputs and low prices paid by middlemen (called aahrtis) leaves farmers with little surplus. Farmers are unwilling to take on a large, expensive debt which – if the harvest is bad – they may not be able to repay, especially when they know that a big chunk of any profit, if the harvest is good, will go to the middleman. So they stick to limited use of inputs, which gives them lower yields and less debt and thus lower risk. Thus it is the cost of credit, and the associated risk, rather than the cost of the inputs themselves, that stops them from investing more.

I’m conscious that we met farmers close to Lahore, who are relatively well-off, and who are already in contact with extension services. So we should be careful about drawing too many conclusions. Based on these few conversations with an atypical group of farmers, I find it hard to convince myself that there are very many practices that farmers could adopt that they do not already know about. That said, there may be some value to encouraging practices that cost the farmer little or nothing to implement – or which save inputs such as using the right amount of urea – for example by issuing timely reminders. But it looks as if the larger gains would come if we could find a way to reduce the risk of increased investment in inputs, reduce the cost of credit, provide high-resolution weather information, or perhaps improve planning and coordination in the use of scarce machinery or casual labour.

It is harder to notice what is missing than what is in front of you. As you may see from the photos, we did not meet any women farmers. We met a female scientist at the rice institute, but everyone else we spoke to was a man. In every conversation, farmers were routinely and unthinkingly referred to as “he”. Yet we know that women provide a substantial part of labour in agriculture, and are hugely affected by all the decisions that are made. If we want to understand what it would take for farmers to adopt practices that would increase their yield and their incomes, we are likely to learn a lot by talking to women too.

I leave Pakistan optimistic but uncertain. Optimistic because the opportunities are huge for large increases in yield and potentially transformative increases in farmer incomes. The constraints are real, but there may be solutions that have a low marginal cost per farmer and so would be hugely cost-effective at scale. Uncertain because we do not yet have enough information to arrive at robust ideas for higher-impact services that we could design and test.

I want to thank Adeel, and all the team, for giving up so much of their time and energy to host us – including taking us to the old Walled City of Lahore to have dinner overlooking the famous Badshahi Mosque (Mosque of Kings) and the Lahore Fort (Shahi Qila in Urdu), an ancient citadel of the Mughal Empire. I look forward to returning to Pakistan soon and hope to combine my next trip with some tourism in your beautiful country.

A new PxD report details fee-for-service private sector collaboration to support free digital extension service delivery to farmers in poverty

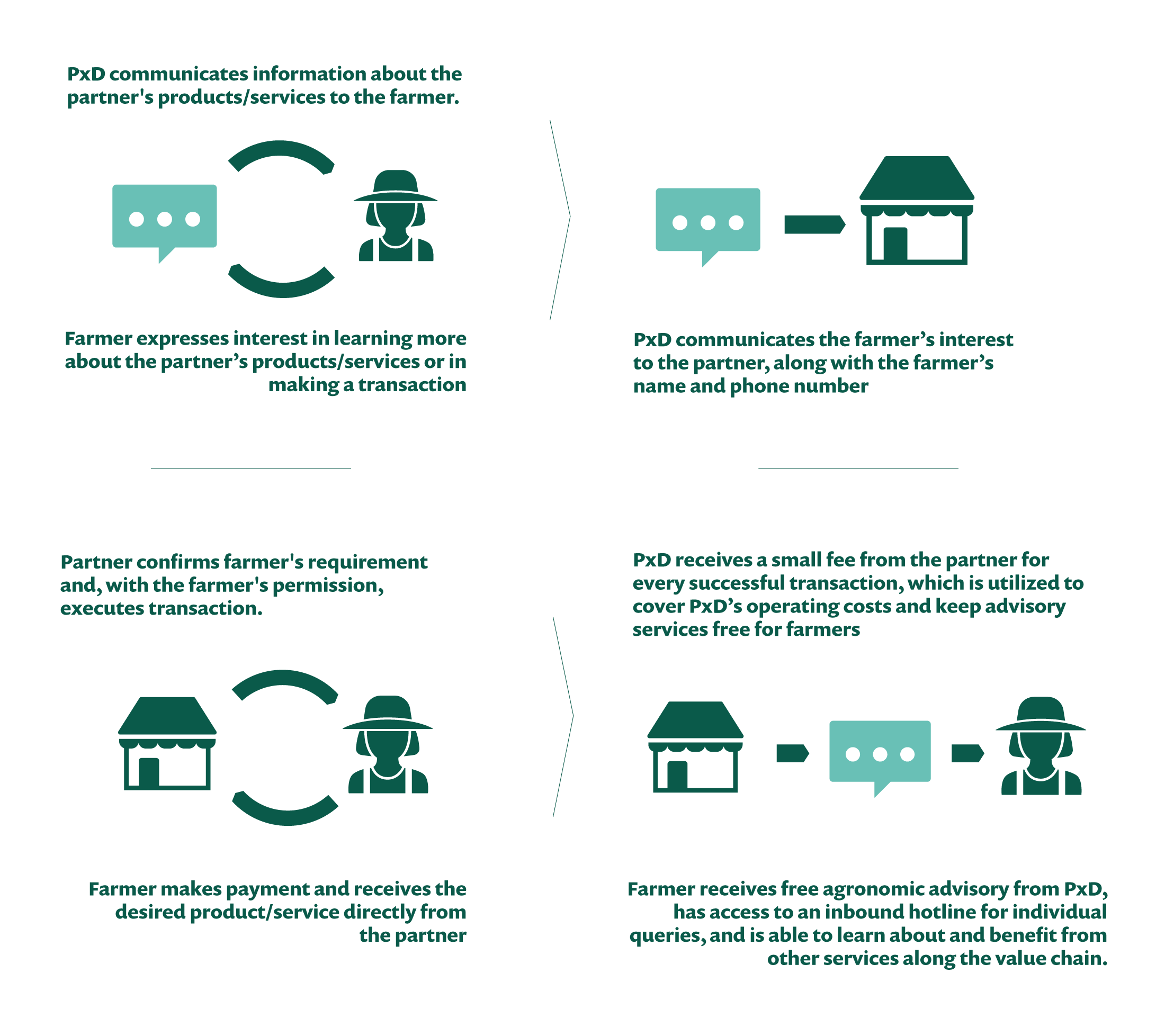

With support from the Swiss Re Foundation, PxD investigated the viability of new forms of partnership with private sector firms to offset the costs of delivering digital advisory information to poor smallholder farmers at no cost to the end-user. PxD initiated a series of pilots that, for a fee paid by private sector partners, connected farmers to agricultural services offered by the same private firms. The pilots investigated the potential for fees derived from partnerships to offset the cost of delivering free information to farmers.

Platforms built and supported by PxD provide scientifically validated and customized digital advice to poor smallholder farmers. This information helps our users make more informed decisions to improve productivity, yields, and incomes, and advance more resilient livelihoods. A majority of our users receive information via platforms we have built in partnership with governments and non-governmental organizations. The overwhelming majority of our users pay nothing to receive information from these platforms. But that does not mean that the information is free of costs. We rely on funding from donors and governments to cover the costs of the service, and sustainable service delivery.

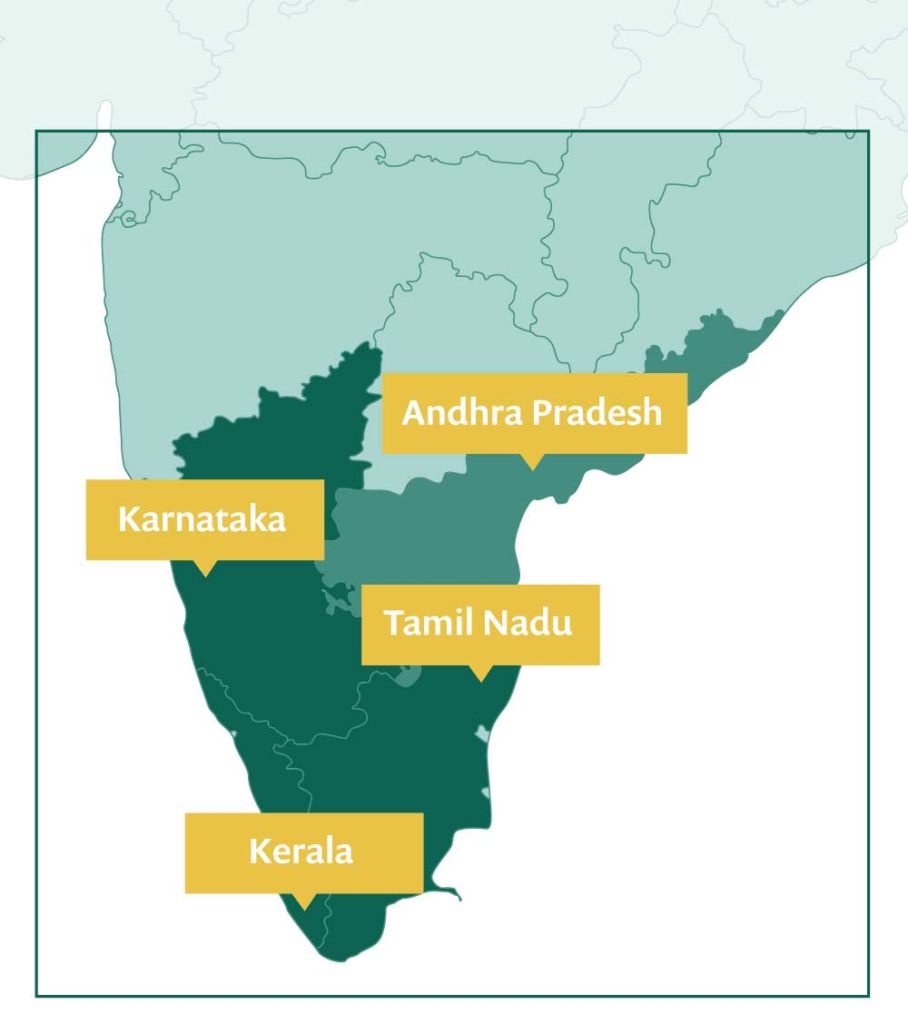

A new report by PxD presents the findings of these investigations. Support from the Swiss Re Foundation enabled PxD to uncover new insights about models of private sector collaboration with the potential for revenue generation at scale and a range of insights about the effectiveness of these services and the viability of new models for partnership. The project also enabled PxD to grow Krishi Tarang, our existing wholly-owned digital advisory service in Gujarat, India, to over 100,000 farmers.

PxD is collaborating with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD) to identify opportunities to benefit poor farming communities through their participation in climate mitigation activities.

The 27th Conference of the Parties (COP 27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is currently taking place in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. COP27 has been dubbed the “African COP” due to its location as well as its strong focus on food systems and agriculture, both of which present pressing climate-related challenges for the continent and many other Global South geographies.

The adoption of improved inputs, new technologies, and practices enabled the agriculture sector to build many ladders for smallholder farmers to climb out of poverty, particularly following the Green Revolution. As yields have increased and farmers produce more than their families consume, selling surplus production has progressively increased farming families’ incomes, reduced the incidence of famine, and improved global food security.

Yet, from drought in the Horn of Africa to the 100-year flood in Pakistan, climate change is devastating smallholder livelihoods. Among its many pernicious effects, a warming climate will accelerate desertification and the incidence of drought, expose farming families and their animals to extended and escalated levels of heat stress, increase the incidence of catastrophic weather events, further erode the viability of marginal land worked by poor farmers, and contribute to the migration of new pests and disease, as well as the intensification of existing sources of blight and infestation in smallholders’ fields.

The impacts of climate change on agriculture are complicated by the fact that the agricultural sector is a significant emitter of Greenhouse Gases (GHGs), particularly methane – associated with livestock and rice production – and nitrous oxide – associated with nitrogen-rich fertilizers and animal waste. Recent estimates suggest that food production accounts for approximately one-third of global GHG emissions associated with human activities.

The effects of climate change, and agriculture’s role in generating GHG emissions, will undermine agriculture’s historic role as a critical engine for economic growth and lifting people from poverty. It is critical that we develop innovative solutions to combat climate change while assisting those who bear disproportionate effects. Marginal livelihoods will need to be further supported to adapt to a changing climate to mitigate the risk of deepening poverty. Concurrently, it is critical that we identify opportunities for poor farmers in low- and middle-income countries to contribute to emissions reduction to secure and advance their livelihoods.

In partnership with the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development (IGSD), Precision Development is investigating opportunities that equip smallholders as agents of climate change mitigation and direct tangible returns, whether through payments for their environmental services or private agronomic benefits, to participating smallholder communities.

This work is guided by the following principles:

- Farmer benefit first: Smallholder farmers can not be expected to pay the price for climate mitigation. Climate-related advisory should support livelihoods and if it is difficult to understand a priori how a specific agricultural practice or technology might impact yields or income, we commit to exploring ways to compensate early adopters as payment for the broader social benefit.

- Consider the cost-benefit ratio: We aim to determine smallholders farmers’ private returns to the adoption of new technologies or agricultural practices, as well as the societal return of such adoption, as measured through the impact of these innovations on our main outcomes of interest in the climate mitigation space (i.e., GHG emissions).

- Replicate and Scale: We aim to deliver impact at scale. We are particularly interested in feasible low-cost innovations with a high potential for impact at scale that can be customized to local contexts.

The results of our investigations will be published as several analytical reports in the coming months. In advance of those publications, this post collates an overview of our findings about practices that are most likely to meet these criteria.

Carbon Dioxide Mitigation through Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW)

Enhanced rock weathering is a new technology to draw down carbon that leverages the natural weathering process of certain types of rocks. Finely ground rocks are applied to soils to drive chemical reactions which capture atmospheric carbon and convert it into stable forms. This stable carbon then flows through groundwater into the oceans, where it can be stored for thousands of years. The application of ERW has significant potential for scale, and permanent carbon drawdown, particularly on agricultural land. However, the implementation of ERW technologies has been limited largely to study environments in high-income countries. Even in these contexts, market, scientific, and technical mechanisms for its successful deployment require further development (i.e. carbon crediting methodology). There is significant interest from climate financing organizations. For example, Frontier – an entity with significant backing from the tech industry – is pursuing an advanced market commitment to fund carbon removal through ERW. However, given the current focus of ERW development in Global North geographies in the absence of a concerted parallel effort in the Global South, it is likely that any future economic benefits accruing to farmers from ERW in the form of carbon offset payments will disproportionately benefit farmers in rich countries. Our research aims to shift some of these actions and benefits to include poor smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries.

Carbon Mitigation through Organic Carbon Strategies (e.g. Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) sequestration)

There is evidence that conservation agriculture practices – such as reduced tillage, the use of cover crops, and intercropping – promote the sequestration of carbon in soils. However, the outcomes of SOC sequestration as a mitigation strategy and the exact amount of carbon stored by different types of soil and under different climatic conditions are still being investigated. For example, because the carbon and nitrogen cycles of soils are closely intertwined, increasing SOC requires sufficient nitrogen. However, increasing nitrogen in soils can create conditions for the leakage of nitrous oxide, which could offset SOC gains.

Conservation agriculture practices such as SOC sequestration do not facilitate permanent carbon drawdown and must be implemented continuously to sustain carbon sequestration, an important consideration when assessing SOC’s potential for persistently increasing carbon drawdown over time. Due to these constraints, there is a growing scientific consensus to emphasize the soil health benefits (i.e. bulk density, improved water retention, etc) and farmer outcomes (i.e. yields, profits) associated with these conservation agricultural practices, rather than solely their carbon sequestration potential. The productivity gains associated with improved soil health can be significant, especially for balancing climate change mitigation goals with global food security needs.

Another potential benefit of SOC sequestration interventions is the connection to nature-based carbon credit projects which can provide smallholder farmers with payment for their mitigation efforts. However, while many SOC-sequestration-based voluntary credit market projects exist (for example, Indigo Ag), the absence of standardized measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) protocols for climate outcomes (like the amount of carbon stored), remains a challenge. This absence of MRV protocols makes it difficult to compare and evaluate the efficacy of SOC-based mitigation interventions, and – as a consequence – complicates efforts to create high-quality credits with higher prices for optimal farmer payout. Moreover, accurately measuring SOC sequestration is likely to require soil sampling, an expensive enterprise with negative implications for the cost-effectiveness of SOC sequestration projects. Concurrently, prices for nature-based projects in voluntary carbon market regimes are low and volatile which may limit the effectiveness of payouts to farmers.

Ensuring that organic carbon strategies, such as SOC sequestration, meaningfully contribute to mitigation, will require coordination and mutual investment in MRV protocols and pathways and careful consideration of the ways in which carbon mitigation projects impact small farmers’ bottom lines.

Nitrous Oxide Mitigation through Precision Nutrient Management

Emissions of nitrous oxide from human activities are primarily driven by inefficient nitrogen fertilizer use in agriculture, particularly overuse. One mitigation strategy with proven potential for reducing nitrous oxide emissions as well as improving farmer outcomes is Site Specific Nutrient Management (SSNM), mainly through decision-support tools like Leaf Color Charts (LCCs). These tools enable farmers to make more informed decisions about the management of nitrogen fertilizer applications based on site-specific needs and their own environment, reducing the overuse or underuse of N-based fertilizers. There are notable considerations to address in scaling and operationalizing these tools, including their calibration across value chains and agroecological conditions, instruments distribution channels, and user experience. PxD gained first-hand experience deploying LCCs on the ground during the implementation of a pilot project to test their effectiveness in Gujarat, India. We are working to find innovative solutions, such as creating a digital LCC, that can reach farmers at scale. Further experimentation and farmer-led innovation will help to address these challenges and increase the use, and subsequent impact, of SSNM decision support tools which have proven potential for nitrous oxide emissions reduction.

Methane Mitigation in Dairy through Improved Livestock Feeding Practices

Milk yields in low- and middle-income countries are significantly lower than their potential, resulting in high methane emissions per liter of milk. A key mitigation strategy to curb methane emissions in livestock farming, particularly for large ruminants like dairy cows, is to improve feeding practices that increase milk production per cow and lower the methane intensity of production. Coupled with a decrease in herd sizes, an increase in milk productivity can decrease net methane emissions in the dairy sector and relieve the overall land pressure of livestock, which can further mitigate GHG emissions. Studies examining the mitigation potential of various livestock interventions underscore the significant potential of improved feeding and digestibility compared to other strategies like manure management, rangeland rehabilitation, and the use of feed additives. For example, in India, the world’s largest producer of milk, improving livestock feeds for local cattle breeds can double current milk yields. Findings from PxD research with smallholder farmers in Kenya suggest that there are significant knowledge gaps about ways to improve livestock feeds, including available methods, some of which are already implemented by peers (i.e. feeding cows sweet potato vines, napier grass, etc). Coupling the optimization of feeds for dairy cows with a parallel effort on market development will not only provide farmers with the tools to intensify production, and thereby mitigate methane emissions, but also generate incentives to do so.

Future Work on Climate Mitigation at PxD

Poor smallholder farmers should have the same opportunities as farmers in high-income countries to be rewarded for contributing to climate change mitigation. PxD is working to identify high-impact opportunities for climate change mitigation that leverage local knowledge in low- and middle-income countries as well as our expertise to combine at-scale product development, behavioral science, and human-centered design with robust experimentation. We are particularly interested in exploring climate financing mechanisms and MRV protocols that bridge the environmental efforts of smallholder farmers and global climate finance.

In the past year, systems built and developed by PxD serviced over seven million farmers in nine geographies. We aim to leverage our scale to generate sizable impacts to reduce GHG emissions associated with smallholder economies. As we do so, we aim to benefit farmers working in the service of mitigation, be it in the form of private returns or payments for environmental services. In pursuing these goals we will need to partner with nonprofits and research institutions to develop robust mitigation programs. We welcome connections with organizations and funders who believe – like we do – that there are opportunities for smallholder farmers to actively mitigate climate change, and that by activating these opportunities, we can add new agrarian ladders out of poverty to those that have come in decades and centuries past.

**this text was amended to include new information on 22 November 2022

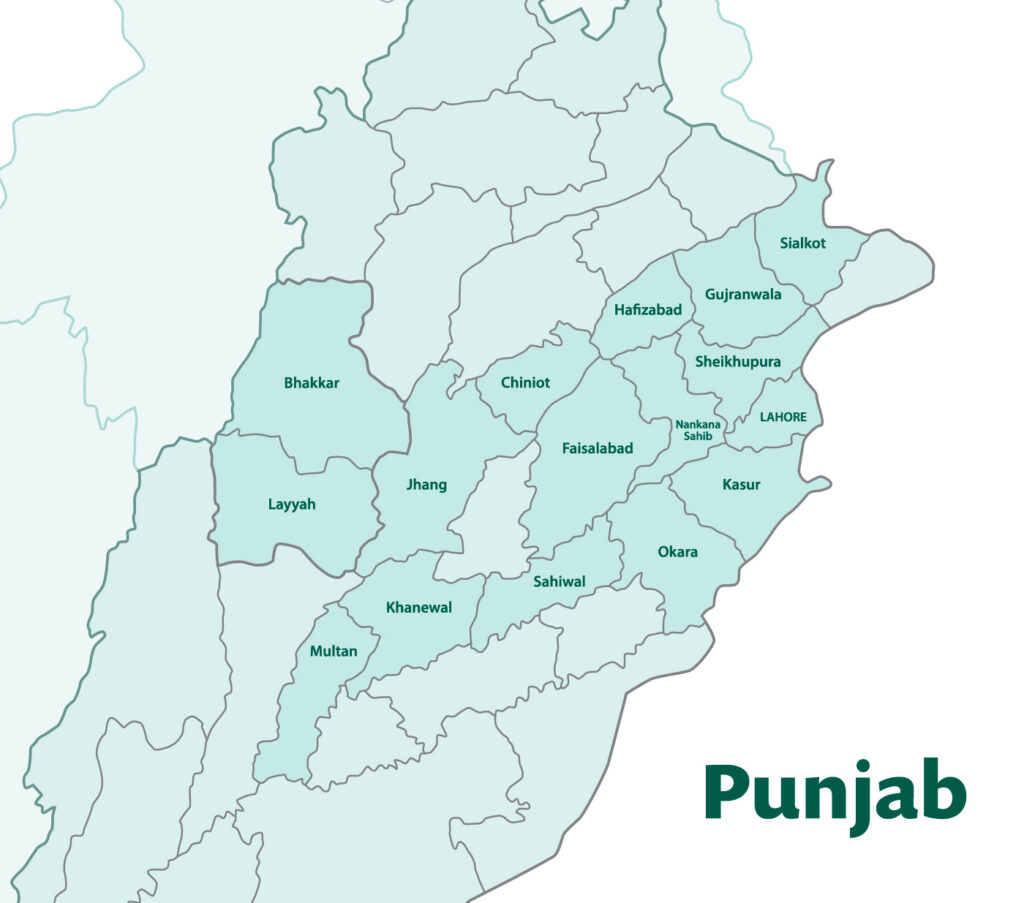

When disease and a heatwave, followed by devastating floods ravaged Pakistan’s Punjab province, PxD’s LMAFRP digital information service, which we implement in partnership with the Rural Community Development Society (RCDS) with support from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), assisted women livestock farmers navigate new and unprecedented challenges. This International Day of Rural Women, we highlight the important role women play in Punjab’s rural farming economy and our work to promote information to enhance more productive and resilient livelihoods.

Introduction

Livestock husbandry and livestock-related products (dairy, meat, leather goods, etc.) constitute an important sub-sector of Pakistan’s agriculture sector: Pakistan is the fourth largest milk-producing country in the world1Sattar, Abdul, “Milk Production in Pakistan” PIDE Blog, pide.org.pk/blog/milk-production-in-pakistan , and the share of livestock products in the generation of foreign exchange is approximately 13%2Government of the Punjab, “Livestock Contribution” , livestock.punjab.gov.pk/livestock-contribution. As is the case in many smallholder economies, in Pakistan, women are largely responsible for the care of livestock and for the production of many livestock-related products, particularly dairy3Ibid..

In rural areas, livestock plays an outsize role in livelihoods, with the Punjab provincial government estimating that “livestock is an integral part (30-40%) of the livelihood of about 30 to 35 million rural farmers”4Ibid.. Livestock-related products, such as butter, eggs, meat, and animal fats (oils), contribute important nutrients for all households – rural and urban – and play a critical role in meeting the nutritional needs of rural children. Further, livestock contribute an important source of continuous income which can sustain poor rural households between seasonal crop-related revenues, and insulate them from shocks5Ahmad, Tusawar Iftikhar and Tanwir, Farooq, “Factors Affecting Women’s Participation in Livestock Management Activities: A Case of Punjab-Pakistan”, mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93312/1/MPRA_paper_93312.pdf..

For these reasons and more, supporting the development and improvement of livestock farming can have a considerable impact on improving the livelihoods of Pakistan’s rural population, and can impact the livelihoods and status of rural women. We believe significant gains can accrue to rural farming families through the promotion of best practices to women. Improved practices can improve yields and minimize losses, leading to increases in income from livestock farming.

Many rural women are unaware of best practices that can optimize outputs associated with livestock, and access to information and economic opportunities can be constrained by cultural and geographic barriers. As documented elsewhere on this blog, digital extension services offer cost-effective and easily scalable solutions with very low marginal costs. In rural Pakistan, where many women rarely leave their homesteads, the portability of digital information offers additional advantages for navigating geographically and culturally hard-to-reach spaces.

Geographic and cultural constraints to attending in-person RCDS livestock training sessions were exacerbated by social distancing introduced to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. RCDS’s in-person activities were suspended in the initial months of the pandemic, but the utility of advisory information increased as rural households navigated new challenges in a time of escalated economic stress. It was at this time that RCDS and PxD initiated a partnership to deliver advice to livestock-rearing women in rural regions of Punjab province in Pakistan. This collaboration, supported by IFAD, provides customized and actionable digital information to livestock-rearing women. Combining PxD’s experience in delivering digital extension services to Punjabi farmers and RCDS’s extensive local knowledge and expertise, the service draws on demographic insights, and cultural practices to deliver information that is accessible, comprehensible, and actionable for recipients.

The resultant digital advisory service has proven to be an effective, cost-efficient, and scalable supplement to in-person training, and is now extended in the absence of COVID-19-related social-distancing constraints. The service demonstrated new advantages when unfamiliar disease- and climate-related threats subsequently impacted rural households.

The Service

RCDS’s experience and local trust in their services have been integral to the success of the initiative. Over the past two decades, RCDS has partnered with local, federal, and international institutions to build a significant rural network to promote and implement development programs to assist poverty-stricken segments of society in rural areas of Pakistan.

Advisory content was developed in partnership with local livestock consultants who were well-informed about local livestock issues and output-increasing best practices. The advisory information distributed by the service covers a wide array of topics, including disease identification, information about and access to vaccinations, disease prevention and remedies, practices to increase milk yields, and guidance on protecting livestock against climate-related shocks.

After conducting a baseline survey to systematically understand the informational needs of women farmers in four districts in Punjab, and the development of advisory information, PxD piloted digital services among 3,160 rural women associated with RCDS. The four districts, in which the pilot was concentrated, are among the poorest districts of Punjab, all of which are located in the south of the province. Given the success of the initial pilot, the service has subsequently been expanded to more than 50,000 livestock-rearing women in 16 rural districts of Punjab.

One of the key components that PxD assessed during the initiative was the extent of knowledge retention by participating women after they received the advisory. Pilot testing in the early stages showed that the advisory information was not only useful but was also retained for a significant period after it was delivered.

RCDS maintains a dataset of women who have either attended in-person sessions of livestock advisory or shown an interest in livestock advisory or have taken a microfinance loan for livestock farming. This data, and its quality, were instrumental in helping PxD deliver the advisory directly to the women via their phones. Furthermore, the data also contained the districts in which each woman resided. This was used to help decide in which of the two local languages – Punjabi and Saraiki – the advisory would be conveyed.

Advisory information is delivered through a voice call. A text message is sent 24 hours before the call to alert users that they should expect a call the next day. This is done to ensure that the advisory is received by women. A barrier highlighted by the baseline survey was limited access to mobile phones on the part of women in the region. Cultural and financial constraints make it far more likely that men have primary access to cell phones. Hence, the time allotted for the voice calls is set at a specific hour in the evening, so that the call is received in the evening when the family is no longer busy with agricultural activities, men are more likely to be home, and when family members can collectively listen to the advisory in their homes.

The voice call has local cultural music layered in the background, to assist the participant in developing trust in and comfort with the message. The information is delivered in the local dialect – Punjabi or Saraiki – to enhance understanding of and familiarity with the recorded message. Further, listeners are told that the advisory is from RCDS since it is well-known as a trusted organization in these regions. As a general protocol, to improve pick-up rates when the voice call is unanswered, another call is placed after a 15 to 30-minute interval.

Lumpy Skin Disease

A significant advantage of digital extension is the ability to send timeous information. This is particularly valuable to address and prevent viral diseases that can have a drastically negative impact on the well-being of the livestock.

In April 2022, Pakistan saw a viral outbreak of lumpy skin disease in cattle. The disease was transmitted between cattle via blood-feeding insects. The disease has a high virulence and fatality rate and killed thousands of cattle in the country.

A significant hurdle that seriously hindered timely prevention and actions to curtail the impacts of the infestation was the lack of baseline knowledge and awareness of the disease. Moreover, misinformation was rife, with misplaced rumors about negative effects of vaccines abounding. Many people mistakenly believed that it was the vaccines that were causing deaths among animals, when animals that had died were either already infected with lumpy skin disease, or were generally sick and should not have been vaccinated at the time.

Understanding these knowledge gaps, PxD and RCDS collaborated to provide timely information about the infestation. Initial infections were observed in the southern part of the country and slowly spread north towards Punjab province, where our users reside. PxD started providing information about lumpy skin before the disease had become widespread in the province.

Our farmer-users were given information about the disease and its virulence, how it is spread, and traditional preventative measures. Following that, to increase the survival rate of infected cattle, users of the service were advised to vaccinate their cattle as soon as vaccines became available. Participants were also informed about how to identify early signs of the disease on the animal.

Anecdotal feedback received by RCDS in the field suggests that the messages were very useful. Users with whom PxD surveyed reported that in many instances they were able to avoid fatal infections in their animals due to timely vaccines, even if their animals did get infected.

The Floods

In the summer of 2022, Pakistan witnessed firsthand the severe impacts of climate change. In March and April, the country experienced a crippling heat wave, followed by a record-breaking monsoon season in Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan spanning June, July, and August. An unparalleled monsoon, coupled with unprecedented melting of glaciers in the north due to the initial heatwave, led to extreme flooding in rivers that flow from the north of Pakistan to the south. The floods are estimated to have impacted at least one-third of Pakistan, including the livelihoods of 33 million people.

Prior to the floods, the extreme heat waves had contributed to a general belief that floods were imminent. To counter the threat, the PxD team in Pakistan worked with RCDS to preemptively identify areas prone to flooding, and prepare advisory messages with useful information about managing floods, and adaptive strategies to protect assets and livelihoods.

A major problem with livestock is their slow mobilization, making them and their rearers prone to becoming flood victims. Timely warnings and regular updates via voice call advisory messages provided participants with information for ensuring the safety of their livestock during the floods. PxD and RCDS made use of their existing program to deliver instructions, warnings, measures, and assistance via voice call messages, to inform participating women and their families about floods and ways to protect themselves and their livestock.

Meeting today’s challenges

The advisory service designed by PxD, and delivered in partnership with RCDS, provided an effective method to deliver timely information to livestock farmers. Due to its effectiveness in the regions where it was being delivered, the advisory service was extended to address other unforeseen challenges, such as the virulent lumpy skin disease, and flooding.

In addition, our project has demonstrated the core strengths of digital communication: it is cost-effective, scalable, and capable of reaching regions and communities that are disconnected or hard to access due to difficult terrain, long distances, or cultural constraints.

Our advisory content was designed to deliver information in a manner that does not require the recipient to have prior knowledge, or education to understand the subject. The use of familiar dialects and carefully crafted messages made the information accessible, easy to understand, and ultimately very effective.

PxD aims to further extend the benefits of digital communication to support other low-cost interventions among rural communities of Pakistan. More specifically, feedback received from users has prompted PxD to further our partnership with RCDS to envisage interventions to support digital veterinary services. We are motivated to continue to harness the power of digital communication to facilitate more productive and resilient livelihoods in rural communities of Pakistan.

From confronting cataclysmic floods in Pakistan, to biblical pest infestations in east Africa, smallholder farmers are on the frontline of an escalating climate crisis. Poor farmers, whose livelihoods disproportionately depend on rainfed agriculture, are particularly vulnerable. The destabilizing impacts of a changing climate will drive many millions of farming families deeper into poverty.

At PxD, we work with millions of farmers to give them the information they need to make more informed decisions about unfamiliar and escalating challenges. We are honored that our MoA-INFO service in Kenya was chosen by the Global Center for Adaptation (GCA) as a case study to highlight the utility of digital information for assisting smallholder farmers as they struggle to adapt to climate change.

In the video below, funded and produced by GCA, Kuboka Maureen, a member of our agronomic team based in Kakamega, is joined by MoA-INFO farmers to explain how the service has assisted Kenyan farmers to navigate climate-related threats.

On 1 August 2022, PxD completed the transition of the management and operations of Ama Krushi – our largest digital service – to Tatwa Technologies Limited, a third-party firm that won a competitive government tender. This post reflects on Ama Krushi’s journey from concept to a fully-fledged digital advisory service providing customized agronomic advice to over three million farmers, and recounts some of the hard truths, lessons learned, and innovations uncovered.

The successful handover of Ama Krushi to Tatwa is bittersweet, marking the culmination of years of work to build a sophisticated digital extension service from scratch. But the transition also means the end of a remarkable journey and a farewell not only to a service we are justly proud of, but also to longstanding colleagues who have transitioned with the service to new management.

In 2018, PxD (then Precision Agriculture for Development) – in partnership with the Department of Agriculture and Farmer Empowerment (DAFE), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), and the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) – launched “Ama Krushi” (“farmers’ friend” in Odia, the most commonly spoken language in Odisha State). Ama Krushi was envisioned as a digital farmer-advisory platform to deliver timely, customized digital advice free of charge to smallholder farmers in the state of Odisha via their mobile phones. Conceived as a build, operate, and transfer (BOT) project, its design envisaged the transition of the management of Ama Krushi to the government of Odisha at the conclusion of the implementation and scaling period. The partners imposed an ambitious target for Ama Krushi: by March 2021, the service would have leveraged research and evidence to build and scale a cost-efficient, statewide digital extension service to serve one million farmers.

As is often the case with well-laid plans, PxD’s journey was very different from what was envisioned in 2018. The initial transition timeline to transfer day-to-day management of the service in 2021 was revised as the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt.

The formal transition ultimately commenced on 1 April 2022 with the initiation of an intensive capacity-building and transfer plan. Tatwa began operating Ama Krushi independent of PxD on 1 June, with continued technical support from PxD staff. Tatwa assumed full responsibility – with PxD becoming entirely hands off – on 1 August. At transfer, Ama Krushi was actively servicing over 3.1 million farmers.

The early days

During the first two years of project implementation, Ama Krushi grew to provide advisory and information for 16 crops across all 30 districts of the state of Odisha. After consenting to be registered, each farmer added to the service was profiled by enumerators. In profiling, a cropping profile for each farmer was created and was populated by our call center team or by our field team on the ground. An accurate profile enabled the service to direct customized content to each farmer, timed to align with critical decision points on the agricultural calendar.

In the early years, the team focused on building out Ama Krishi’s core service: an interactive voice response (IVR) push call service that delivered weekly advisory information tailored to each farmer’s profile information, and a complementary farmer hotline. By placing a missed call to the hotline, farmers received a free return call, enabling them to access a library of advisory information and frequently asked questions, and the option to leave messages to be serviced by agronomists via a recorded push call within 48 hours (typically fulfilled within 24). While any farmer could ask a question, only profiled farmers received weekly advisory.

By analyzing trends in engagement and directly interacting with users during field visits and focus groups, we gather information to inform new products and service innovations that are relevant to the needs of users. Two prominent examples include the integration of Kitchen Garden Advisory, aimed at women who engage in subsistence farming, with our regular programming, and the expansion of our advisory to include non-crop-related value chains, specifically livestock and fisheries. During the first two years of operation, the Ama Krushi team explored different avenues for expansion while deploying A/B tests to iteratively improve modes of information delivery. At the end of 2019, Ama Krushi was serving over 620,000 farmers.

Similarly, in response to demand from farmers and our partners at DAFE, PxD added new digital channels to expand our reach to smallholder farmers. Radio remains an important medium for information dissemination in rural India. Accordingly, PxD piloted advisory dissemination via a local community radio station in early 2019. By September 2020, the pilot had evolved into a formal collaboration with the Community Radio Association of Odisha, with Ama Krushi broadcasting weekly advisory across 12 community radio stations. Community radio enabled us to reach many more farmers who were not registered on the service and advise them on how to register to receive the full suite of AK digital services.

We also added a live call center (LCC) in December 2019 so that farmers could call in to be connected to a live agent. Given farmers’ limited digital literacy, we observed that many farmers had trouble navigating the inbound hotline. To make the service more accessible, DAFE requested that we build out an LCC to help reduce the technological burden on farmers. Propelled by the government of Odisha’s request to have all services offered by Ama Krushi available under one short code, the LCC was added to the main menu in February 2021 – now, should the farmer wish to, they can call 155 333 and choose whether or not to engage with a live agent to have their concerns addressed. This is supplemented by an escalation system that ensures that the farmer receives the answer on the spot or through a push call within 48 hours.

In early 2019, PxD also ramped up the training and onboarding of extension workers and other village-level champions, which allowed us to grow the number of agents that could sensitize farmers on the Ama Krushi service. It also meant that content could be disseminated via a hybrid model to these groups (e.g. IVR and district-level WhatsApp groups).

Scaling through the pandemic

At the start of 2020, in consultation with our colleagues at DAFE and BMGF, we formulated a transition plan to transfer day-to-day management of the service to a third party in 2021, as per the initial BOT agreement.

No sooner had the execution of the transition begun, however, than our plans were upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, which presented challenges that we (and most organizations across the world) did not have the experience or knowledge to contend with. We reconfigured our operations to continue offering the service while adapting our operations to work-from-home.

The move to a fully remote, work-from-home operation underscored a cornerstone advantage of digital extension services: the ability to operate at times and places that traditional extension services cannot reach. In the first month after the pandemic, we transitioned our hundred-strong call center team to work-from-home arrangements, established a system to service agriculture-related distress calls (for example, being stopped by police when taking perishable crops to market after the issuance of a statewide authorization communique) and questions from farmers during the nationwide lockdown, and assisted the government of Odisha to deliver key agriculture-related updates to remote areas. The Ama Krushi team demonstrated remarkable resilience, maintaining and then building their capacity to serve farmers. The Ama Krushi service was available every day of the nationwide lockdown and subsequent phases of physical-distancing protocols, .

Despite significant operational adjustments imposed by the pandemic, Ama Krushi surpassed its target of servicing one million farmers in November 2020, five months ahead of DAFE’s initial target. Bolstered by Ama Krushi’s success, the government of Odisha issued a directive defining new targets and goals in March 2021. With additional support from BMGF, we received approval to launch advisory channels to support livestock and fisheries on the Ama Krushi platform. The government of Odisha also revised the end goal of onboarding 1 million farmers by March 2021 to 2.5 million farmers by June 2021.

While these requests reflected the Odisha government’s faith in Ama Krushi and our team, the revised targets and deadlines presented challenges for the handover of the service. COVID-19-related concessions had allowed for the extension of the original transition timeline from March 2021 to September 2021, but the addition of livestock and fisheries went beyond the scope of the original agreement and required us to test, launch, stabilize, and hand over a new version of the service within six months.

Undeterred, the Ama Krushi team quickly commenced piloting and testing to support the development of livestock and fisheries advisory, launching the two new advisory channels in January and April 2021, respectively. Concurrently, we continued to leverage research and user feedback to improve the service and began preparing operations and management materials in preparation for the handover.

Collating and organizing information about the service and the platform operations was an extensive exercise that required the creation of a large vault of documents. These documents detailed how the service worked (even as the service continued to change), outlined a framework to facilitate capacity building to support the transition of workstream ownership from PxDs’ team to government officers, and created a learning agenda to document and monitor the transition and inform future efforts.

Transition

Coordinating with the government during the pandemic was challenging – understandably, as their focus had shifted to the resolution of pressing issues. Coupled with the adjustment to work-from-home arrangements and personnel changes in critical official roles, discussions, and decisions to guide the Ama Krushi transition slowed.

At a meeting in March 2021, the government committee, chaired by the then Principal Secretary, met to decide what form the Ama Krushi transition would take. Early considerations had included embedding government staff within the Ama Krushi team, but given the complexity of operations, the government indicated a strong preference for a procurement process to contract out management of the service to a third party, while retaining government oversight and ownership. Naturally, this development led to a series of internal considerations. What form would the transition now take? How would the third party engage with the government and the program? What would happen to program staff who had been trained with a view of being transitioned to government management? How would the service remain government-owned and -funded in the long term?

After exploring the route of procurement via impaneled agencies with the Government of Odisha, PxD and DAFE came to the conclusion that, given the size and complexity of Ama Krushi and its teams, the identification of a new implementing partner would require a full public procurement process facilitated by a request for proposals (RFP). 1An RFP is essentially an open tender:an advertisement for a service that the government requires (in this case, the management of the Ama Krushi program) is put out for a minimum period of time with a set of eligibility criteria. It invites bidders to submit a tentative budget and uses a careful scoring system to identify the best-qualified party for the task. In July 2021, the government published an RFP inviting candidates to take up the tender. The plan of transitioning the service in 2021 seemed unlikely.

The PxD team running Ama Krushi was funded by both BMGF and DAFE and comprised “ground teams” running everyday operations like profiling, content delivery, fieldwork, and IT maintenance, in addition to a dynamic data and management team. The RFP proposed a different model: the entire program would now be funded by DAFE, with the management team comprised of a Program Lead – to be filled by a government official – in charge of a program management team staffed by the organization identified through the tender, who in turn would manage the work of the ground/operational teams. We had expected that the ground teams would remain in place given that they are critical for program continuity, but there was no guarantee that the new entity would absorb the existing operational team. Suddenly, the future of our 120-people strong operational team looked uncertain.

Handover to Tatwa

Given the repeated delays and shifting parameters of the transition, we agreed with DAFE and BMGF to further extend the transition timeline to 31 March 2022.

At the conclusion of the RFP process, the government appointed Tatwa Technologies Limited as the third-party firm to take over Ama Krushi’s management and operations. Following the announcement, PxD facilitated an extensive capacity-building program premised on in-person workshops and intensive shadowing. Tatwa wisely chose to retain the program’s existing ground teams, ensuring that Ama Krushi’s operations would run smoothly, with little to no inconvenience to Ama Krushi’s now 3.1 million farmers. On 31 May 2022, PxD successfully transferred the day-to-day management of the Ama Krushi program to Tatwa Technologies. After an additional two months of technical support, PxD is no longer involved in the delivery and development of Ama Krushi’s services.