Twelve months, 2,800 farmers and a new country: Colombia UK Pact Project

- August 1, 2022

- 11 minutes read

In consortium with Rare and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), PxD received a one-year grant from UK PACT in December 2020 to support the implementation of a project to promote sustainable and productive agriculture through behavioral change. PxD’s Colombia team – activated remotely under pandemic conditions – implemented the project over twelve months, sending climate-smart agricultural advice to smallholder farmers in Colombia’s Meta region. The main focus of the advice was to provide farmers with “win-win” recommendations to concurrently increase crop productivity and reduce environmentally harmful farming practices. The project was PxD’s first in the Americas and was unique in a number of respects – including a high penetration of smartphones among the user base, and an environment and digital culture profoundly shaped by a legacy of conflict.

What was the program about?

PxD, Rare, and TNC partnered to provide a mixed digital and in-person agricultural extension service called “New technologies, mentalities, and practices to transform Colombia’s agricultural sector.” PxD implemented an all-digital component of the project named “Un Mensaje por el Campo” (A message for the field), a two-way SMS service intended to increase crop productivity through the implementation of climate-smart practices for 2,800 farmers. PxD and Rare jointly designed and iterated 37 weeks of content timed to the production cycle of three crops – plantain, cocoa, and coffee – with a focus on practical knowledge such as composting, pruning, and pest and disease management. In addition to advisory promoting climate-smart production of these three primary crops, we also sent content to support the cultivation of perennial crops (the most common being avocado and citrus). To complement the digital approach, our partner Rare implemented an extension service to promote the adoption of sustainable practices by “innovative producers” (understood to be farmers more inclined to include sustainable practices in their day-to-day routines). Concurrently, TNC conducted a community-based pilot to measure carbon emissions.

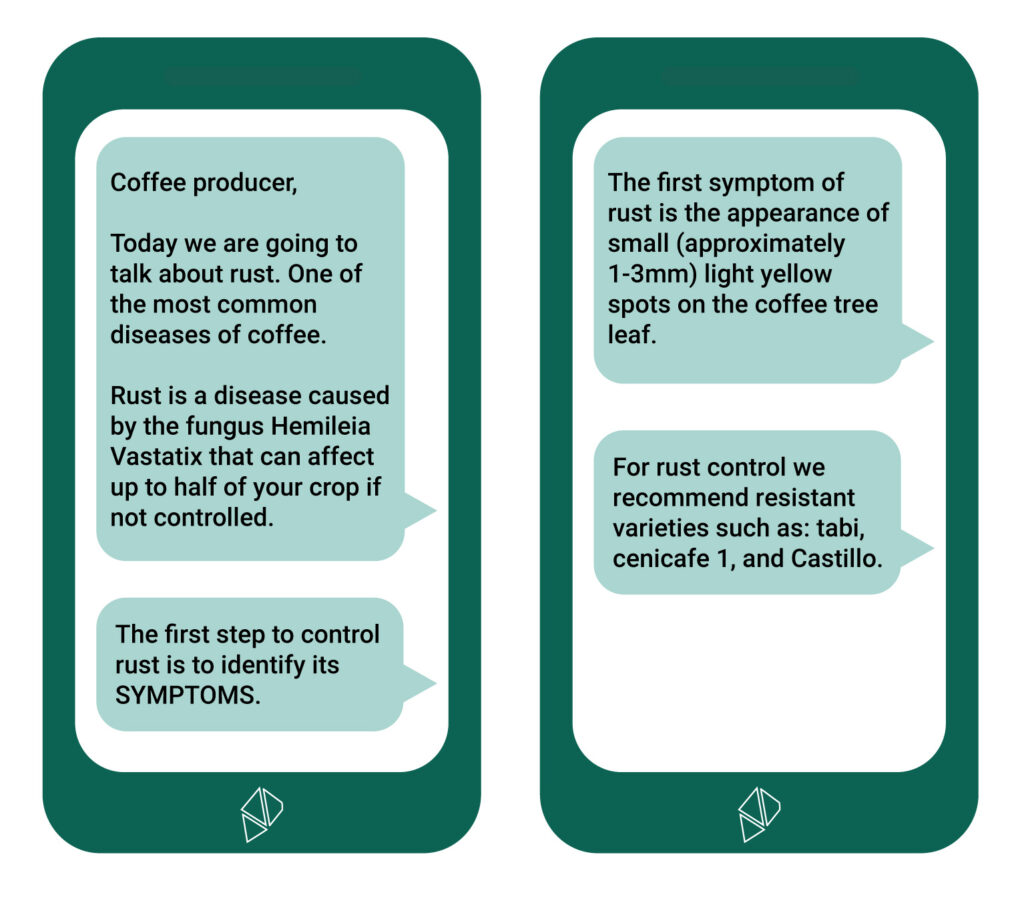

Our digital platform featured multiple channels for farmer communications: Farmers received push-SMS recommendations weekly between 5:30 and 6:30 pm on Wednesdays and Fridays. In weeks when we were promoting complex topics, we sent recommendations three times a week. Farmers could also send an SMS with the word “menu” to access a repository of all content shared to that point and pull any information they needed. The menu was updated weekly as new content was pushed to farmers. Users could also send questions to our short-code at any time to be answered by our agronomist.

Farmer profile information received through PxD profiling surveys:

- 40.2% women users

- 66.3% reported owning a smartphone

- 35.5% have access to some form of extension services

- Farmers reported average land holdings of 8 hectares.

- 93.8% reported completing at least primary education

- 67.8% reported owning their land and 21% leased the land they worked. Of the remaining 11% of respondents, 8% worked collectively owned land shared with other farmers, 3% were share-croppers renting a piece of land from a permanent owner.

Armed history of the Meta region in Colombia

Building a new program in a region deeply scarred by conflict was demanding and gratifying. Even after the peace agreements, farmers in conflict-affected areas report very limited access to extension services as a result of reluctance on the part of in-person extension providers to visit farmers in areas perceived to be unsafe. Digital extension services can be particularly relevant in these contexts, as digital services can be deployed and managed remotely and can be customized to a region’s particular needs.

In general, farmers in post-conflict regions report limited trust and interaction with government services, including public extension services, and are often reluctant to interact with organizations they do not know.McNamara, P. & Moore, A. (2017). Building Agricultural Extension Capacity in Post-Conflict Settings. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12010/17029.

To improve the likelihood of success, a key challenge for the teams was to build trust in our service while building a program capable of reducing information asymmetries.

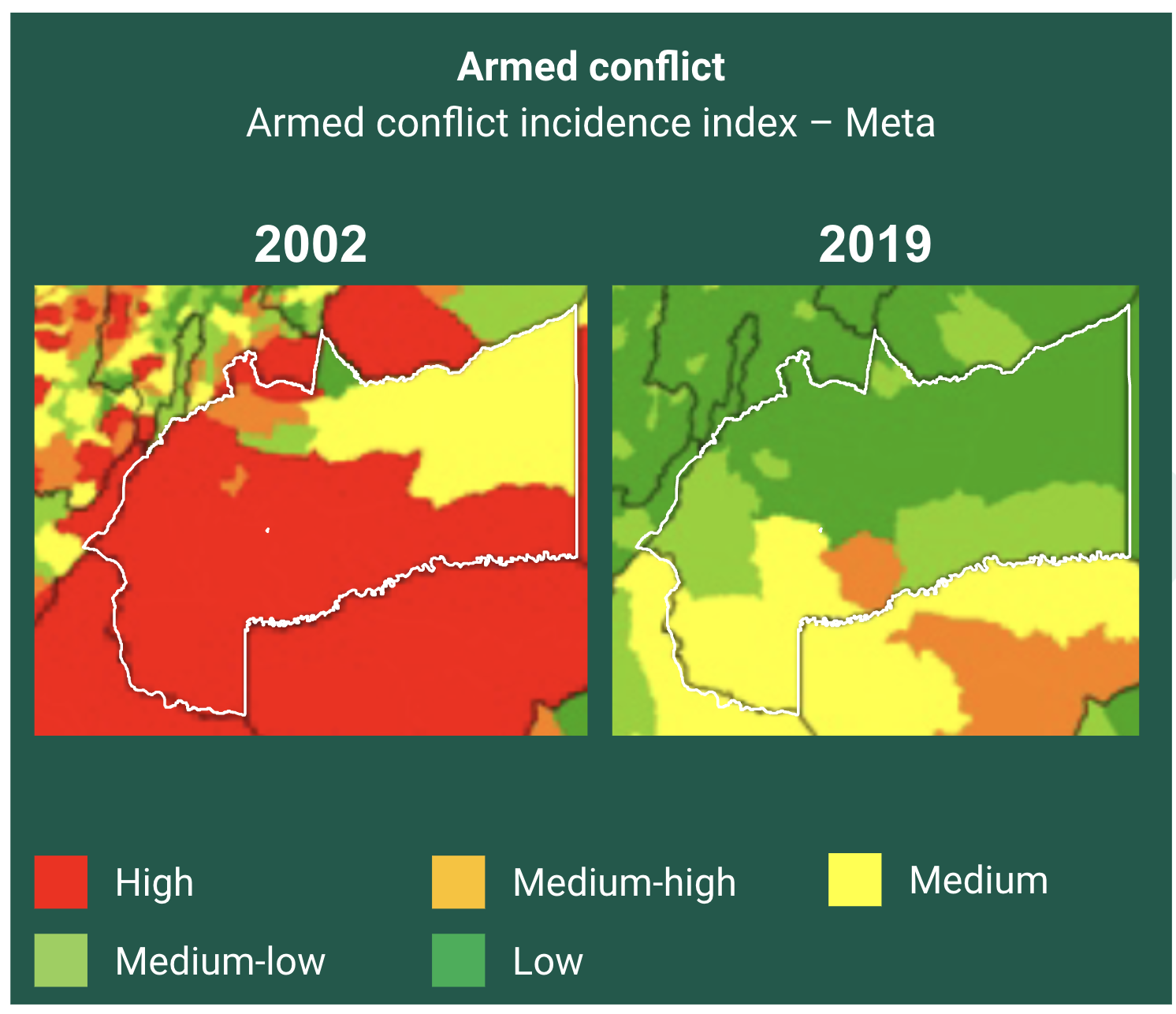

The Meta was the fourth-most conflict-affected region in Colombia in the early 2000s. The map above compares the armed conflict incidence index of 2002 to that of 2019. The index synthesizes six key conflict-related variables: homicides, kidnappings, anti-personnel landmines (number of events), force-displacement, coca crops, and armed actions (from illegal armed groups).

Source: National Planning Department (2021)

How did we measure results from engagement?

Our team used monitoring data to improve our contextual understanding of our user base, to help us identify opportunities for service improvement, and to measure program and intermediate outcomes along a theory of change. As a two-way SMS service, we measured engagement in two ways, which we dubbed “active” and “passive” engagement.

Active engagement was defined as engagement we could measure through PxD’s Paddy platform, the in-house tech platform we used to deploy Un Mensaje por el Campo. Such engagement included accessing the menu (by sending an SMS), replying to content threads, and sending an SMS question to our shortcode. We adopted the “reply 1” feature for most messages to enable users to choose what content they wanted to receive. A generic message such as, “Today we are going to talk about [topic of the day, state the importance of the topic, reply 1 if you want to learn more” invited an initial response. By the end of the program, 23% of users had actively engaged with the service (649 users had actively interacted with the platform at least once as of February 2021). Messages that did not require the “reply 1” feature were usually about topics we considered essential and wanted all farmers to read about. It is thus very likely that a much greater share of farmers read the messages but did not respond. We defined passive engagement as users who reported reading SMS messages via our monitoring surveys. For passive engagement, 56% of our users reported reading our SMS in the polling survey.

Polling survey findings

We conducted a monitoring and polling survey approximately six months after the commencement of the service. The polling survey aimed to measure practice adoption and service satisfaction. Results for the three primary practices were as follows:

- 36% of respondents reported preparing and applying compost, a practice we emphasized, and 16% (of the 36%) reported doing so for the first time. The soil quality and lack of organic content in the region make composting one of the most economically efficient ways for farmers to replace chemical fertilizers. This is especially relevant in light of significant price increases for agricultural inputs.

- 67% of respondents reported pruning their main crop, and 20% (of the 67%) reported doing so for the first time. Pruning is known to be one of the most effective ways of preventing pests and diseases without using chemical fertilizer.

- 60% of respondents reported applying chemical fertilizer, and 14% (of the 60%) reported doing so for the first time. Given that most farmers use chemical fertilizer, we provided advice on how to use it more efficiently, rather than expecting all farmers to switch exclusively to sustainable practices. Our recommendations focussed specifically on reducing the overuse of chemical fertilizers to minimize environmental degradation and reduce costs.

Respondents were generally enthusiastic about the service. In terms of service satisfaction:

- 75% of respondents reported the content as being relevant to the needs of their crops.

- 88% of respondents said they were likely to recommend our service to neighbors.

- 70% of respondents reported sharing content with their networks, and 59% reported having done so in person. (Great opportunity to explore how farmers not in the service benefited from the information!)

Challenges and learnings

We confronted many challenges over the 12 months of the program. Some had been encountered previously by other PxD teams, and we greatly appreciated their support in navigating the same challenges in a new country. Other difficulties were exclusive to Colombia, and we had to learn to face them with different strategies. We divided our challenges and learnings into content creation, trust-building, and SMS service and network.

Content creation:

To ensure our content was accessible to farmers, we explored ways to time the messages based on evidence from what had worked well in other PxD programs and on Colombian farmer feedback. After a few weeks of sending content, questions such as “How often should we send messages?” and “How often should we repeat content?” started to arise. Following support and advice from other PxD teams, and analyzing evidence from A/B tests, we decided to repeat the most important content at least twice to increase users’ exposure to it. We also implemented “weekly recaps” for which we dedicated a day to highlighting the most important messages of the week.

We also explored opportunities for customization so that farmers could maximize the benefit of our service based on their specific situation. After talking with the Nigeria team, which implements strategies such as creating personas to create the best possible message, taking into account different characteristics, we were able to decide on the best next step. We agreed that after crop segmentation, having customized content based on the agro-ecological zone (rainfall regimes) and based on the users’ technological level would be an appropriate next step. Unfortunately, the project’s implementation horizon did not allow sufficient time to achieve this level of customization.

We were also able to improve efficiency in the content creation process along the way. We worked towards reducing the number of iterations it took to get to a final message, while ensuring that the content remained of a high quality. By the end of the 12-month implementation period, we had settled on the following standardized template to design an SMS: Introduce the topic → Explain why the topic is important → Explain our recommendation → Explain how the activity should be performed.

Building trust

One of the most important steps when introducing a digital extension service is creating a relationship with farmers. A strong relationship translates into trust, which increases the potential impact of the service through increased engagement, asking questions, and recommending the service to loved ones. However, previous high exposure to armed conflict made farmers initially reluctant to receive and interact with the service. Moreover, users’ phone numbers were collected by Rare (our on-the-ground partner) and farmer associations, and many users were unaware of their enrollment in the advisory service when they started receiving messages. To improve our relationship with farmers, we implemented four strategies:

- Leverage local networks to build trust in the service. We contacted leaders of farmer associations and mayors of municipalities and asked them to help us spread awareness of the program through monthly meetings with farmers and WhatsApp groups.

- Always send SMSes from the same short code so that farmers become accustomed to it.

- Conduct onboarding calls to all farmers in our database to introduce the program to them and facilitate trust-building, and complement the calls with fieldwork. (We also conducted the onboarding call when new farmers were added to the program.)

- Provide users with an easy name they can think of when talking about the service, e.g. “Un Mensaje por el Campo” (some of our users had our contact saved with this name!)

SMS service and networking:

High variance in connectivity quality among municipalities in Colombia in general and in the Meta region in particular was a significant challenge. Some users only received messages when they went to the municipal center (e.g. on Sundays when farmers traveled to buy groceries). This is both a blessing and a curse, as while farmers did eventually receive the messages, the messages could not be precisely timed, which could hinder trust. Repeating content and leveraging weekly recaps to ensure priority recommendations were getting across to users thus became more critical.

Another characteristic of the Colombia program was that users were unfamiliar with SMSes despite the medium being considered the best option in light of connectivity challenges. The most common problem we faced was that users were not in the habit of checking their SMS inboxes, and some did not even know where their SMS inbox was. To address this particular issue, we did a pilot using WhatsApp to complement the advisory service, sending WhatsApp messages to 1,200 farmers over two months. On average, 76% of users read these messages. This also highlighted how vital ongoing training is to familiarize users with the platform; one-time training is not enough. While we cannot do a perfect comparison with the self-reported reading of SMSes, WhatsApp messages suggest a promising channel for increasing engagement with the service in future programs.

Conclusion

Starting a new program in a new country and on a new continent was challenging but very rewarding. Despite some key team members living outside of Colombia in the initial four months of implementation, we built a strong team during the COVID pandemic and launched a new service that was innovative for PxD in many ways, providing digital extension services through WhatsApp, exploring new ways to build trust in a post-conflict environment, navigating poor connectivity, and prioritizing content in the context of a new country. We learned how to implement a sustainable and impactful program in Colombia and are now working towards new opportunities and partnerships in Colombia and the wider Latin America region. We hope to soon leverage all of our knowledge and experience from this project and continue to grow our presence in this part of the world.

Stay Updated with Our Newsletter

Make an Impact Today